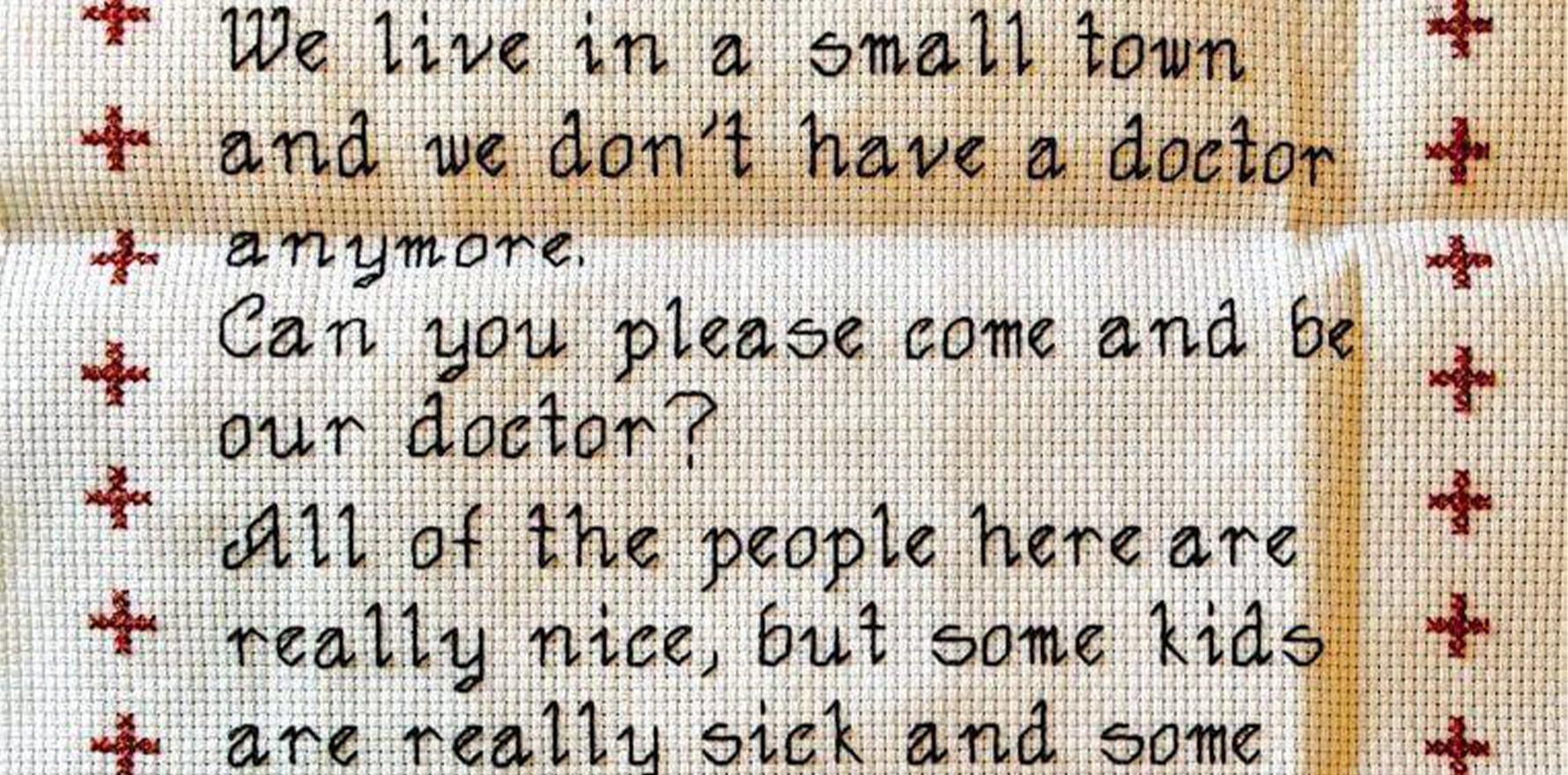

It’s no secret that rural areas have an increasingly serious shortage of doctors, but are current measures to increase interest really working?

Attracting, recruiting and keeping medical graduates for rural areas is quickly becoming the 50-million-dollar question that Canberra can’t answer, but a group of researchers believe there is still time to turn it all around.

Throughout Australia, GP practices in rural towns – some with upwards of 1800 patients on the books – are closing up shop altogether, having been unable to keep enough staff.

Meanwhile, hospitals in regional areas are also beginning to buckle under pressure, with a shortage of GPs and locums meaning emergency departments struggle to keep a regular VMO on-call roster.

Just this year, Regional Health Minister Mark Coulton has made several big promises in terms of funding, committing $49.7 million to the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine to provide 100 rural generalist GP training places each year, as well as $200 million per year to broaden the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program.

But with so much at stake for rural communities, will this be enough?

Refreshingly, it just might be.

“What I find most interesting is that it’s a very optimistic outlook that we end up with,” Dr Remo Ostini, a researcher at the University of Queensland’s rural clinical school, told The Medical Republic.

“[We currently have] a very positive, strengths-based approach [to training].

“What we’ve found is that we can work with what we’ve got and get much better outcomes if we work with it a little bit differently from how it’s being done now – it just takes is a slightly different mindset.”

According to Dr Ostini, who was the coordinating editor of a recent MJA supplement on the rural workforce shortage, challenging the notion that medical training is best done in metro environments will be critical going forward, for doctors of all stripes.

“Medical students are much more open to working in rural areas if they’ve been trained in rural areas,” he said.

“Some of that builds on rural backgrounds – if the students themselves come from a rural area, and trained in medical school in a rural area, they’re much more likely to actually want to practice or to end up practising in a rural area.”

The MJA supplement itself was funded by the UQ rural clinical school and contained four original research papers.

These investigated the characteristics of the existing workforce, the professional identity of rural generalists, trainee and supervisor experiences and principles for future efforts.

“Rural settings differ from the metropolitan setting in which most specialist, including physician, training currently occurs,” Dr Ostini wrote in the opening editorial.

“This results in a mismatch between current specialist training and rural specialist care needs that contributes to an insufficient rural medical workforce and the associated poor health outcomes.”

Essentially, Dr Ostini believes that the National Rural Generalist Training Pathway is not only on the right track, but that other specialty colleges should follow ACRRM’s lead.

“We’ve got the skeleton of how to do it, as well as the evidence for why we think people should take this approach, why we think it’s a good approach to follow, but it’s certainly not going to be easy,” he told TMR.

“It will take funding, similarly to the way the rural generalist programme through ACRRM – the whole general practice, primary care approach – has had been funded.

“I think I think that model has worked quite well.”

Associate Professor Peter Hill, another UQ rural health researcher and lead author on the chapter looking at identity, told TMR that any future training models would have to ensure they met the diverse needs of the rural workforce.

“Our research says you can’t speak on behalf of this group, so there needs to be multiple intersecting strategies that address the individual identities that we’re working with,” he said.

Professor Hill, who collected qualitative data from rural doctors, medical colleges, researchers and government agencies, also said that the key to attracting more rural doctors likely lies in changing how rural work is perceived.

“At the moment, much of the training sees a half-year rotation to a rural centre as being a necessary exposure, but it’s often imagined in fairly punitive terms by trainees,” he told TMR.

Instead, he would like to see a model where rural training was the norm, rather than the exception.

“Those who are interested in a generalist option for rural Australia [could train] in a major rural centre, and flip into a metropolitan centre to finesse their training as they need it,” Professor Hill said.

He did acknowledge, however, that the scale of the change which is needed to reform rural medical care was not likely to happen quickly in specialties outside of general practice.

“We’re dealing with a workforce that is certainly not highly industrialised, it’s not a vocal, agitating workforce,” Professor Hill told TMR.

“It’s a workforce that values its contribution, but is quite inward-looking and individual in its orientation.

“We’re not looking at the kind of industrial action that drove the GPs for a better deal in rural Australia.”