Year 2 of covid was exhausting, terminally so for some GPs; but if you’ve made it this far, things will get interesting (mostly in a good way).

Congratulations, you’ve made it (almost).

The year 2021 was surely one of the most challenging and testing years ever for the GP profession, so if you’re still here, well done – you deserve a few medals from the country and your patients.

Perhaps you will even manage a decent break to lick your wounds before resuming battle in early 2022.

If you’re exhausted and wondering “is this all really worth it?”, here are three things that emerged in 2021 that we think have set in motion major changes for the GP profession (and much of Australian healthcare overall). While surely challenging, the changes are mostly going to see the profession innovate, change and thrive, on its own terms, into the future.

- Freedom: the beginning of the end of an imprisoning bulk-billing paradigm

A few weeks back, the president of the RACGP broke ranks with government during the organisation’s AGM and declared to members that they should all start thinking hard about abandoning universal bulk-billing.

Dr Karen Price, who had until then largely played the usual presidential game of dancing politely with the federal government, departed from script and set out a very clear objective for the GP profession in that meeting. And the simple logic behind it: GPs have no leverage with government while bulk-billing rates remain high, and that, combined with the fact that post covid there is no money left in any government budget, means that GP pay is never going up again while we are reliant on the government for that to happen.

Hence, start dismantling bulk-billing. Ouch.

Subsequently, we got inundated with stories from GPs who had already started the journey, some in a big way and who had been doing it for years (read Dr James Moxham’s piece here and this one from Dr Imaan Joshi ), and it turns out that in most circumstances it really isn’t that scary a step to take. And you can mitigate risk as you go.

Australian Doctor did a survey asking who now intended to make a change to their billing profile and so did we.

In the Australian Doctor survey, 73% of GPs said they intended to reduce the amount of bulk-billing they do by 25% or more in the coming year. Forty-five per cent said they’d reduce it by a pretty staggering 50% or more. The full Australian Doctor survey result story is here.

We got slightly different results in our survey on the same topic (we asked slightly different questions), but the same big trends seem to be there: GPs have an intention en masse to start increasing their levels of mixed billing substantively.

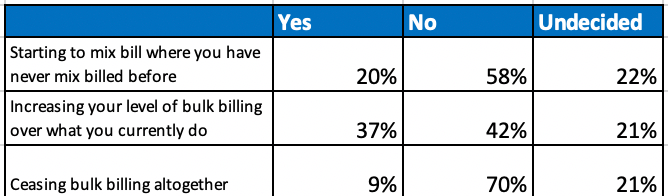

Our full results are going to be published early next year (we asked a lot of questions and it makes for quite a lot of data) but here’s a snippet that should make you feel you’re going to be in good company if you do decide to break ranks early next year and start upping your mixed billing levels a lot.

Question: are you actively considering…

Both surveys suggest something has shifted substantively in the psyche of most the profession, something that Dr Price possibly was reading when she made her statement.

Of course, in any competitive system you will get some hold-outs.

Some corporate practices – Cornerstone, for instance – aren’t going to change their model, and if the surveys are right, such a shift will probably make their optimised bulk-billing centre model on scale a more attractive business for investors. They will be differentiated.

And probably, there should remain some centres in most suburbs that offer patients an ongoing simple and free option.

But the days of big business bulk-billing – the Primary Health Care days – are over. Only an optimised and specialised few will be able to make this model work, moving forward, because the government isn’t going to increase Medicare rebates meaningfully any time soon, if ever, now.

This trend is issuing in a massive change for general practice: Freedom (feel free to start humming George Michael here).

If practices can establish systems and patient cohorts that recognise their value and accept a lot more mixed billing, general practice has a new path to better remuneration.

But abandoning bulk-billing and establishing a patient base that accepts your value and pays you more for what you do over time isn’t the end game.

It’s just the beginning.

- The telehealth soft shoe shuffle

For all the absolute mayhem covid has created for the profession, its legacy (hopefully there will be a time when we do look back and think of it in legacy terms) is mostly going to be all upside relative to “before covid”.

It has forced us all to think much harder about how to do health much better and allowed government to experiment where they would never have dared experiment so boldly before.

Without covid, telehealth would most likely never have happened.

And without rebated telehealth, there would have been significantly more carnage for everyone.

But it turns out – as we should have expected – that telehealth was something of a soft shoe shuffle by the government.

The government giveth and then it taketh away.

You notice that when the federal government wants to announce something substantively negative for the profession, they’ll do it as close to Christmas as they can manage, right?

Enter the 30/20 rule, which we spotted on Thursday (and we still managed to write about here – note to Department of Health, we in the medical media go on holidays next week, not this week … we’re not the ABC).

The 30/20 rule neatly puts an end to any dreaming about the massive potential utility of telehealth to both patients and their GPs.

In their infinite (financial) wisdom, the DoH has dug deep, and with no research, data or analysis to back up its move (none we’ve been told of), has decided that if a GP on any given 20 days in one rolling year claims more than 30 telephone items, then it’s straight to the PSR gulag for them.

It’s a predictable and dumbarse new rule.

Predictable because the DoH can’t afford telehealth the way it was rolled out during covid, especially when we get to post-covid budgets. So it had to cap it somehow.

Dumbarse because such a complex rule is a going to be a complete nightmare for any GP to keep track of, and it’s going to add that little bit of extra PSR gulag stress to each working week.

What GP will be able to keep count of their top 20 days in respect to doing telehealth calls and make sure the daily figure – of services, not even patients – stays under 30 (hopefully the patient management systems will come to the rescue with some sort of warning system, but that’s not likely because it’s going to cost them to do it and they have bigger problems at the moment)?

What happens when there are a series of emergencies with a certain set of patients and you just lose track?

And one more thing. Along with this change, the DoH decided to scrap the rural loading on telehealth items, which was 50%. So in the bush, where surely the phone and the odd video call are a lot more meaningful and frequent than the city, not only are you getting a giant overall cut to the amount of telehealth you can do, you are getting an added 50% cut.

Jeeez … have they really thought that bit out?

This could actually end up killing some patients, if you think about the importance of telehealth in the bush.

But no one should be surprised.

This is a financial decision (and equation), not a quality-of-healthcare one. And getting the PSR involved works, because the PSR is a financial instrument of fear we all understand all too well.

So how is any of this a good event for the future of the profession (as I sort of promised in the intro)?

Well, you didn’t have telehealth before covid, and now at least you’ve got it forever in some form, moving forward – albeit in a much-strangled format.

And telehealth is like one giant foot in the virtual-care door that the government can now never remove.

It’s showing us the potential and the opportunity of doing things differently and more efficiently, and it’s going to keep showing us that in all sorts of ways.

Soft shoe shuffle or not, telehealth is a genie that the government can now never put back in the bottle, 30/20 rules or not.

Would you like one more metaphor here (no, no more, please stop)?

Telehealth is like a wise traveller sent to us from the future of healthcare to show us the path to connected medicine and the utility of integrated virtual care .

It’s not the future itself. It’s actually pretty basic so far.

But it’s showing us there are ways to do things much better (and often without too much extra expense) with simple technology.

As it evolves – it’s a genie the government can’t control, remember – it’s going to start posting signs to a whole series of emerging connectivity and virtual technologies that are going to change how GPs work in the future.

Really?

- The connected GP will be a GP with multiple new revenue streams

Covid has entirely changed the government’s mind and direction on the importance of better technology in the medical system. And we aren’t talking about the My Health Record here, which in many senses is already a bit of a relic compared with what is coming down the pipeline.

With this change of mind, and attitude, has come a lot of money to expedite many of these technologies. Saying you intend to spend $17 billion to fix aged care in the next few years, and you intend to fix it as far as you can using some of these technologies, was always likely to create a bit of market buzz and start investors salivating.

And it has.

If you are watching healthcare technology company valuations in Australia at the moment and can’t understand what is going on – $340 million for Medical Director, $200 million for Genie, $100 million valuation on a consumer healthcare app that still has less than $10 million in revenue – then have a quick look at what is going on in the US.

Healthtech investment is going nuts. It’s going nuts because, finally, digital transformation, which has affected so many major markets so significantly, is making an appearance in the health sector. Covid gave it the push it needed. People needed to solve problems much more efficiently and quickly, so rules got overlooked and technology got tried. And it worked.

About six weeks ago, the person who heads up digital health strategy and implementation for the DoH, Daniel McCabe, sort of let the cat out of the bag on a conference call to a gathering of members of the Medical Software Industry Association (MSIA).

As things are, the majority of the members of this association aren’t ensconced in the sort of technologies that are making investors light-headed. Most have been around for a long time and their technology, though sophisticated and great IP in its time, is old, server-bound technology. By server-bound, I mean, it’s not “cloud-based” technology, which is what has driven digital transformation in markets such as finance, travel and retailing, and where the government wants to go.

McCabe is smart, driven and politic.

He’s not the sort to freak out anyone but on this call, he pretty much made it clear to everyone that all the systems of government are going to the cloud, that the government now recognised the utility of the cloud, and that while there would be a sensible roadmap and a timetable to give everyone a chance to get on board, everyone had better get on board as soon as they could.

He didn’t actually say it this bluntly. He’s politic. But we did, in a story HERE.

Next year, Services Australia’s Medicare billing will be cloud-based and all providers wanting to get paid by the government will need to be able to talk to this new cloud-based system. The PBS will also be on the cloud by then, for much better utility.

Now most of these vendors don’t need to reinvent their software in the cloud to talk to a cloud-billing system. They can build integrations, so that their old technology talks to the new technology.

But if they keep doing that, at some point in the not-too-distant future, they will go out the back door trying to write such integrations. It will get too complex and expensive because everything is moving to the cloud now and there is a tipping point where healthcare providers will change over.

The cloud, by way of simple explanation, is just software and services (e.g., data storage) that run on the internet, instead of locally on your computer.

It’s sort of that simple. And sort of isn’t.

Most GPs don’t get what the cloud can and will do to healthcare.

Why should they?

Some even still think that being able to see and hug their computer boxes means their data is more secure (it’s really not, everyone, I promise).

“Cloud schmoud”… I get that a lot from some very smart GPs.

But that’s OK.

No one ever asked for the mobile phone, or an iPhone.

It just arrived one day and things got (largely) easier to do and more efficient for us consumers.

And that’s how it should be (and probably will be) for GPs.

It’s coming – in the form of connected cloud technologies. McCabe thinks so, and he’s someone who has a lot of government authority and budget to make things happen. Telling the MSIA to get on board on cloud is a very big signal.

When it does come, GPs, who are very clearly the centre of our healthcare universe if we are really going to get on top of the oncoming chronic-care tsunami, should end up far more connected to patients, to hospitals, to their local aged care facilities, to their allied support network, and to specialists.

If you put two and two together on this trend, then GPs are facing a decade of enormous potential opportunity and that opportunity should open up significant new revenue models in things such as servicing local aged-care facilities, servicing local public hospital infrastructure with significant new “hospital in the home” programs, and even doing work on the side for private health insurers, which increasingly want what we all want, which is fewer people going to hospital.

This sort of technology isn’t going to be here working perfectly for you next year – although it’s available for those entrepreneurial types who really want to go there. There is risk but there will also be reward for those entrepreneurial GPs who see the value in better connectivity and facilitating virtual care as a part of their services.

2022 will reveal some fascinating work being done by many of the new cloud based based vendors.

One government department is about to reveal a huge project to build an entirely interoperable and mobile healthcare ecosystem for more than 85,000 users which includes primary, allied, hospital and specialist care, all seamlessly linked via the cloud.

Such a system is idealistic in some respects as it will be built without the legacy that besets much of general practice today, transitioning business models and without the complication of a mixed up federal funding paradigm.

But it will show what can be achieved.

Change is on its way.

2021 was the watershed year

In 2020 covid just smashed us around as we panicked trying to work out how to manage it.

By 2021, we had learnt a lot, and we knew we had to break some rules and change how we do things.

In 2022, the legacy of 2021 and covid’s first two years will start to unfold for general practice.

No, the government isn’t ever going to pay GPs much more. It really can’t afford to.

So 2022 marks the beginning of a whole lot of new ways of doing things for general practice: much more mixed billing (after you make the right comms and marketing plan for your patients, of course), telehealth (albeit, fewer than 30 services in 20 days for now), and the beginning of the era of the cloud and far better connectedness in Australian healthcare.

Not so bad after all, perhaps?

We’re taking a break – or you’re taking a break from us – for three weeks. See you in January.