Under pressure over its approval of the Alzheimer's drug, the agency has narrowed the set of candidate patients.

Amid an intense backlash in the month after the US Food and Drug Administration announced the ‘accelerated approval’ of Biogen’s aducanumab, the FDA has called for an independent investigation into its own review process.

It has also narrowed the prescribing indications for the controversial Alzheimer’s drug.

FDA acting commissioner Dr Janet Woodcock requested the investigation, citing ongoing concerns over interactions between representatives from Biogen and the FDA, that “may have occurred outside of the formal correspondence process,” which she said could undermine the public’s confidence in the decision to approve the drug.

Given the ongoing interest and questions, today I requested that @OIGatHHS conduct an independent review and assessment of interactions between representatives of Biogen and FDA during the process that led to the approval of Aduhelm. pic.twitter.com/iWJNxdZ5Cs

— Dr. Janet Woodcock (@DrWoodcockFDA) July 9, 2021

Allegations of off-the-books meetings were documented in a lengthy report by the health news site Stat, but the FDA’s close involvement in helping Biogen prepare its application had already raised eyebrows.

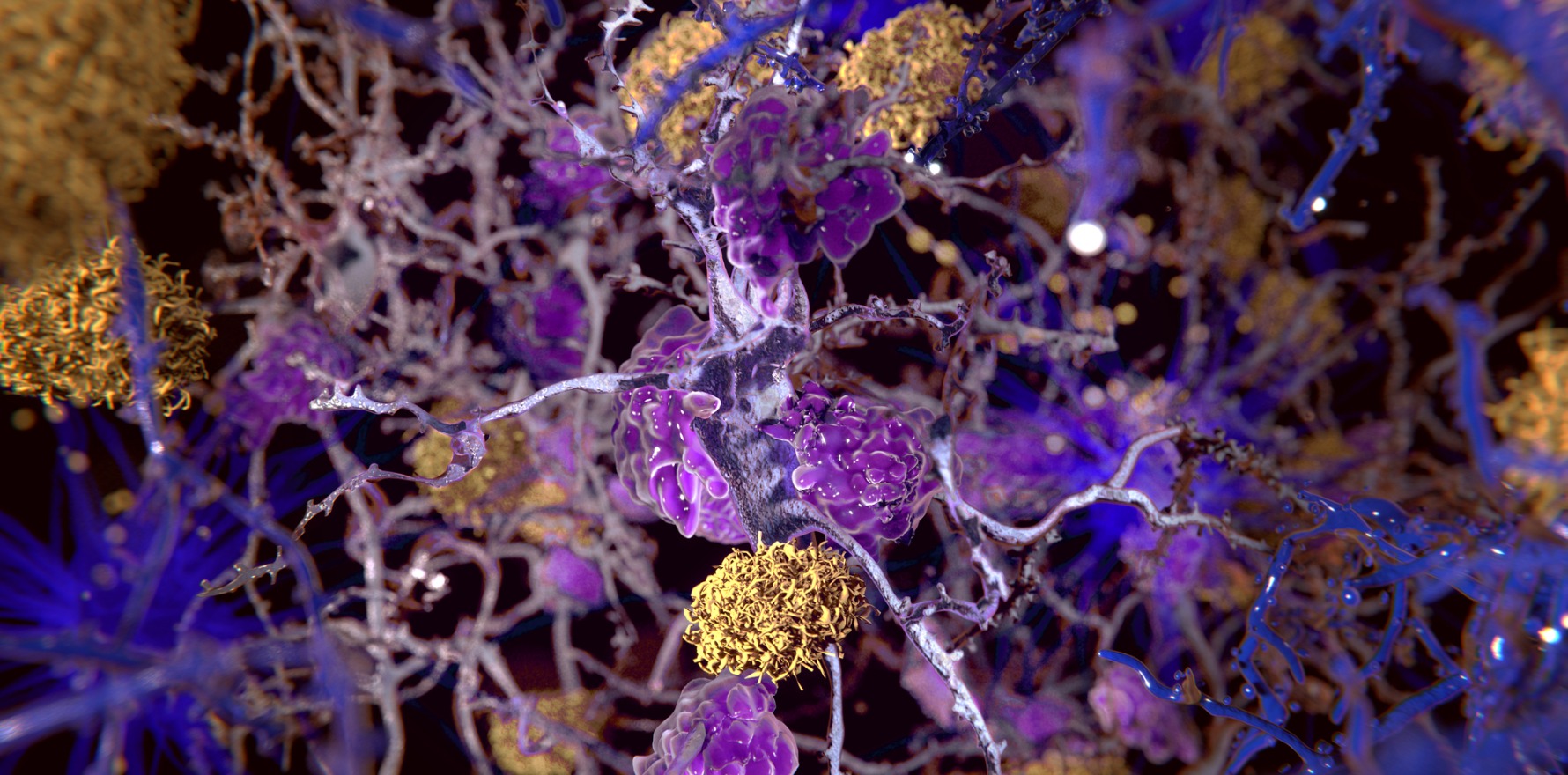

In response to fierce criticism over the strikingly broad prescribing indication “for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease”, the FDA has also updated aducanumab’s label to limit who it is recommended for. The label now says aducanumab (marketed as Aduhelm) “should be initiated in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which treatment was initiated in clinical trials”, and clearly states that there is no information on safety or effectiveness at other stages of disease.

Harvard Professor of Medicine Aaron Kesselheim, one of three experts who resigned from the independent advisory committee that had recommended against approving aducanumab due to lack of compelling evidence that it would slow cognitive decline, tweeted that the changes to the label were a start, but not enough.

“This is a welcome step and addresses one of many problems with this drug approval, but the FDA/Biogen should be doing much more now to help patients by actively combatting misperceptions about this drug,” he wrote.

Aducanumab’s new label now also notes that continued approval “may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s)”.

Accelerated approval allows for drugs to be approved on the basis of surrogate outcomes – for example reducing amyloid plaques, in the case of aducanumab. But although the process mandates further clinical trials, even negative results are often not enough to remove a drug from market.

In a white paper published in April, the not-for-profit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) highlighted just how fraught the accelerated approval process has become, noting that “In some instances, study sponsors fail to conduct or publish required studies at all.”

In other cases, such as bevacizumab for metastatic glioblastoma, the FDA has allowed drugs to stay on the market even after the required trials failed to demonstrate an effect on the primary clinical outcome, ICER found.

In fact, a review of confirmatory trials of 93 cancer drugs that had been granted accelerated approval found that just 20% improved overall survival.

As for aducanumab, the surrogate endpoints are questionable, given that evidence that reducing amyloid will translate to reduced cognitive impairment has been severely lacking.

The US office of the inspector general has yet to announce whether it will accept the FDA’s request to investigate the drug’s approval.