One in five patients cancelled or delayed GP visits during covid, and the rate was higher among those with the biggest risk of heart disease.

Hundreds of Australians may die of preventable heart-related deaths in the coming years, in the wake of covid disruptions.

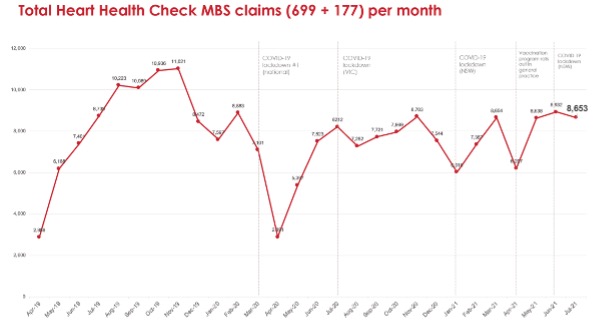

“With the introduction nationally of lockdown measures from March to May 2020, the average number of Heart Health Checks conducted during the period fell by nearly half, or just over 5,100 a month,” the Heart Foundation’s Risk Reduction Manager, Ms Natalie Raffoul, told The Medical Republic.

Before covid, more than 9,200 Australians get checked each month, according to an analysis of MBS items 699 and 117.

That equated to more than 27,000 missed checks, according to Heart Foundation modelling.

States least affected by covid, such as WA and Queensland, had the highest screening rates in the country (about 30 per 1000, compared with 25 nationally).

“A Heart Foundation survey of approximately 10,000 adult Australians from April to December 2020 revealed that one in five had cancelled or delayed medical appointments with their GP,” said Ms Raffoul. “The proportion at high risk of heart disease, as advised by their GP previously, had the highest rate of cancellations or delayed appointments (36%) from July to December 2020.”

Using the absolute CVD risk distribution of patients in the general population, and the treatment of those at moderate and high risk of heart events who weren’t receiving blood-pressure- and lipid-lowering therapy, the Heart Foundation estimated that around 350 people would die of avoidable heart-related deaths in the coming five years.

CVD is still the leading cause of death in Australia, but numbers have been steadily decreasing. Figures published by the AIWH this week show a decline of 22% between 1980 and 2019, due to a combination of a reduction of some risk factors, clinical research, advances in treatment, care and management, and improved detection and secondary prevention.

Could the dramatic drop in screening jeopardise this trend?

Professor Garry Jennings, the Heart Foundation’s Chief Medical Adviser, warned that “silent conditions” such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia could have worsened or been missed altogether.

“This could create a dangerous situation and a backlog of people who need preventative heart health care for years to come, placing additional pressure on general practice,” he said.

Professor of General Practice Mark Morgan, who chairs the RACGP Expert Committee for Quality Care, said the Heart Foundation’s message was very important, but that relying on the use of MBS items 699 and 117 wouldn’t pick up all heart disease monitoring by GPs.

“Many GPS, if they do a comprehensive preventative medical consult, will simply charge a 36, a long-consult item number, if it’s more than 20 minutes long. They won’t necessarily bill the heart-check-specific item number because they’ve covered a number of aspects of a person’s life and risks simultaneously.”

But he said there has been “a big drop-off” in routine preventative checks. “I’m sure that there is a price being paid for taking our eye away from long-term prevention, in the face of the pandemic, lockdowns and reduced visits to GPs.”

However, he was optimistic that the medical fraternity could turn things around.

“As we get used to living with and around covid and a vaccinated population, we really need to pick up again on prevention,” Professor Morgan said.

Technology can help by using data already routinely collected to identify who’s at risk and prompt GPs to invite them in, or address it at the next booked appointment, suggested Professor Morgan, who is involved in the design of one such system.

Relying on existing calculators alone allowed some patients to fall through the cracks, he cautioned.

“There are groups of people – for example, chronic kidney disease – that put you in an automatic high risk, and then there are fudge factors that should be applied, like having serious mental illness, for example.”

“Calculators that might come out next year are likely to include additional factors that will be part of the algorithm for calculating some of these risks.”

The 2012 Absolute CVD Risk Guidelines are being updated. The Heart Foundation’s Ms Raffoul said new guidelines are expected to be published in October/November 2022.

“The guideline update will incorporate the latest evidence and approaches in CVD risk assessment and management that may include a revision of risk factors necessary for risk estimation,” said Ms Raffoul.