The demise of good general practice has been predictable for decades. The question is whether the community is happy to let it go.

Like many of my colleagues, I couldn’t sleep last Monday night after watching the ABC’s 7.30 report.

I was trying to make sense of the articles and newspaper reports claiming doctors were rorting Medicare to the tune of $8 billion a year.

The evidence for this claim is poor. It conflates fraud, “low value care”, misunderstandings of the overly complex MBS schedule and over-treatment motivated by profit. However, to the community, the rhetoric is much simpler. Greedy doctors are “ripping off” the taxpayer and doctors are treating patients inappropriately for financial gain.

There are instances of fraud, over-billing and inappropriate practice in any profession, and medicine is not immune. We should be responsive to legitimate criticism, and the community have a right to understand and expect good care and appropriate stewardship of the Medicare dollar.

However, the scale of this claim is immense. If it were true, it should trigger a fundamental rethink of the way medicine is financed and governed. However, if it is a vast overestimate of the problem, and many experts believe it is, the claims of widespread, callous, deliberate profiteering are a deeply damaging misrepresentation of who we are as a profession.

The impacts of the rorts narrative on general practice

GPs across the country are feeling the impact of recent attacks on our competence, professionalism and ethics. Patients are refusing to pay because we are apparently “rorting the system”, our staff are experiencing escalating abuse. More insidiously, media campaigns damage trust, and we need trust to be able to work with our patients to achieve health outcomes. It is exhausting and demoralising to endure these attacks on our reputation, but more importantly, it’s another nail in the coffin of general practice.

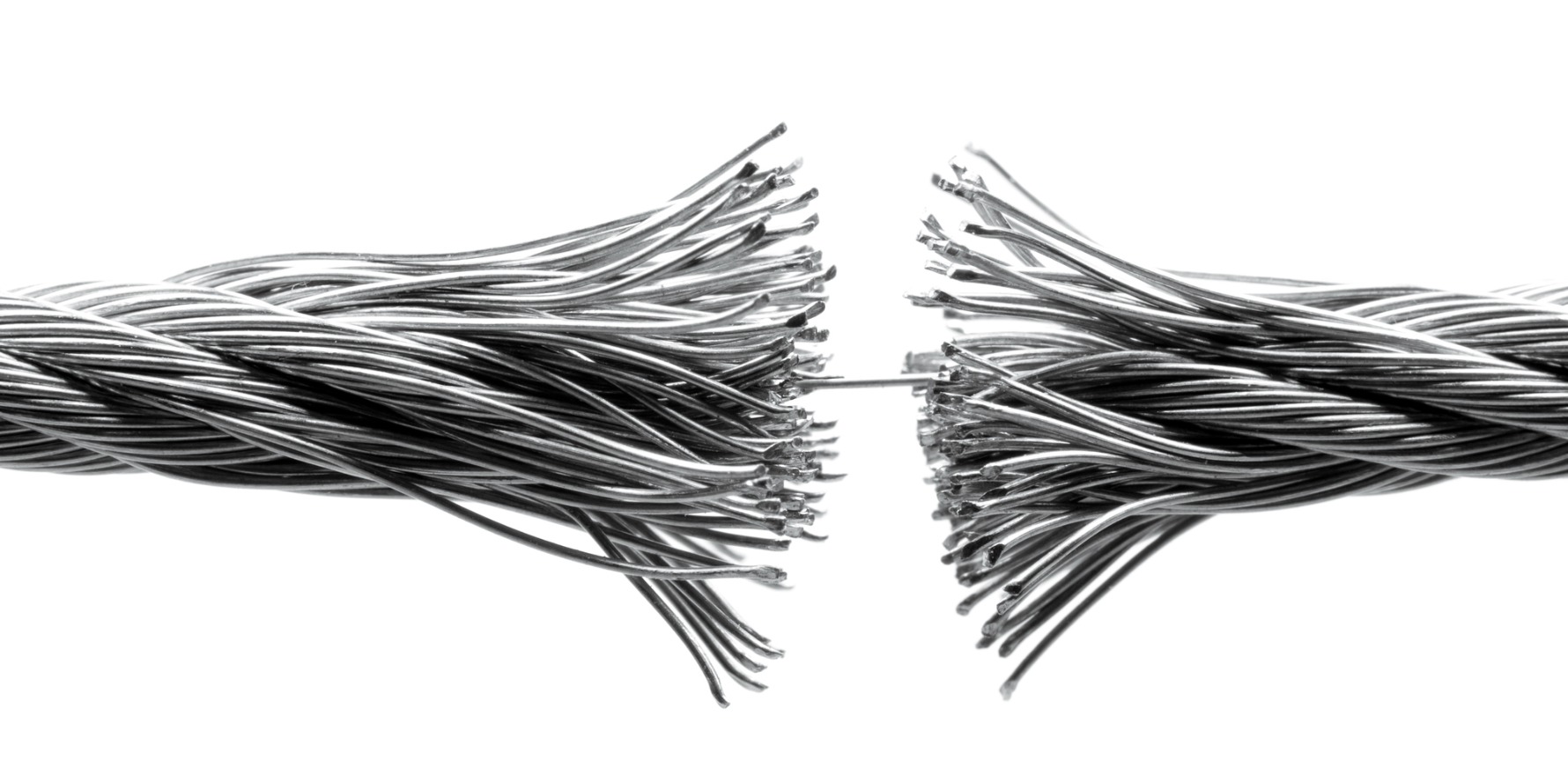

Caring for the community is a privilege and the genuine gratitude we feel for the patients who simply thank us when we go above and beyond is precious. But the balance is shifting, and the cost for us is beginning to outweigh our commitment to serve our communities. Which is why general practice is shrinking rapidly, and the GP is becoming an endangered species in the ecosystem of medicine. Frankly, our habitat, the environment in which we can flourish or even survive, is under threat.

The attacks on my beloved profession in mainstream and social media in recent years have made me feel sick. But I have finally recognised what was going on. The “heart sink” feeling we are experiencing demonstrates that the relationship we GPs have with governments, organisations and some sectors of the community has become emotionally abusive.

The social contract between GPs and the community they serve

I’ve been a GP for 30 years. We do what we do as part of a social contract. When I trained, that contract was clearer. I agreed to give my patients and community the best medical care I could with the personal and professional resources I have. Not just procedural or intellectual services, but compassion and care. “Cum Scientia Caritas”, serving my community with my head and my heart.

With hundreds of my colleagues, I’ve reflected on the millions of hours we have donated to keep the health system afloat over the years. Home visits. Deeply challenging consultations with people in mental health crises who have nowhere else to go. Calls on a Sunday from my patients who are dying, or suicidal, or just stressed beyond their capacity to cope. Setting up respiratory clinics and keeping up to date with the constant shifts in policy, process and evidence during covid-19. Begging the hospital systems to accept my vulnerable patients. Policy contributions. Research. Teaching. Advocacy. Donating the gap between the Medicare rebate and the cost of care so the nurse in the clinic gets paid and the clinic stays open and the patient gets food on the table. All the unpaid overtime as an intern, resident and registrar.

I could go on. And on and on and on.

And yet the other side of the social contract, the professional respect, the financial support for our care and the granting of autonomy to practice to the best of my ability is slowly eroding away. In its place are compliance measures. Like most doctors, trained for 12+ years in complex care, GPs did not train to simply impose protocols on patients. We were trained to think. To evaluate the evidence, consider the patient’s context and point of view and then negotiate the best outcomes we can achieve with this patient at this time with the resources we have available. Evidence-based medicine is the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.” Following a protocol is a vast underestimate of what you need me to do. The paradox of primary care tells us that forcing GPs to follow protocols reduces outcomes.

And yet the idea of “low value care” is often expressed in simplistic terms; take the evidence from studies examining one disease in a narrow population, and assume the outcomes apply to the patient in front of me. This was not what evidence-based medicine was meant to be, but it is how it is being applied. Which is why we have policies based on studies of patients who actually complete an intervention without considering the impact on the patients who drop out, or the people who never opted in. It’s bad science, poor policy and terrible medicine. But still, the rhetoric around low value care continues.

The relationship between GPs, the commonwealth and the community

There are so many parallels between what I feel as a GP serving the commonwealth government and other abusive dependent relationships. There are tactics – keeping us exhausted. Financial coercive control, which in our case leads 47% of GPs to underbill for fear of the PSR. Crazy-making contradictions in which we are lauded as “the cornerstone of the health system” and, in the same sentence, asked to shoulder more unpaid burdens of care. Dismissing concerns of GPs about patients safety as “turf war” arguments. Frank abuse in our clinics. And now public attacks on our professionalism and ethics. It is important to recognise that intent is not important here. It doesn’t matter what is intended when a perpetrator behaves this way. What matters is the perspective of the survivor.

Medicare has rorted me and my colleagues for years, especially female GPs. They have sucked me dry by cashing in on my empathy, relying on me to donate increasing bucketloads of compassion to plug the holes in the health system. The government knows most of us will do this in the service of our vulnerable patients, so it’s an easy characteristic to exploit.

Yet the “greedy, immoral doctor” narrative just won’t die. It’s too convenient for everyone, especially those who have a business model predicated on managing the “crisis”.

GPs are such convenient scapegoats, because everyone knows we will not turn our backs on our communities. We have been rorted for decades. There are thousands of us who hang on in a system that abuses our empathy – in aged care, mental health care, rural and remote, Aboriginal health.

We are not grubs. We are fools.

Policing “quality”

There is a revolving door of people who are convinced they could do my job. I still remember a close colleague attending one of my lectures on mental health care in general practice and saying with genuine surprise: “I had no idea there was any theory behind what you do”. Nobody really understands what we do, because if it were simple enough to explain in a sound bite, it wouldn’t need 12 years of training to achieve. We have also defunded attempts like BEACH which successfully quantified what we did for decades. However, the lack of relevant data on our activity or our outcomes doesn’t stop criticism from a variety of sources claiming we fail to do “it” well enough.

In the past three years there has been audit after audit after audit. There has been an increasing sense of threat from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and the Professional Service Review, including recent moves to publish our names publicly before a case has even been heard. We are all trying to protect our vulnerable young colleagues who are leaving in droves because they can’t cope with the public vitriol. Worse still, we are dealing with the suicidal doctors targeted by all and sundry who would rather drive off the road than go in the front door of their hospital. Dealing with the grief of their colleagues when they do die (and they do – here and here) is heartbreaking.

The result is an over-burdened workforce which feels constantly under attack. Defensive medicine is bad medicine. It is not good for the doctors, and it achieves poor outcomes for the patients. There must be a balance. Over-governance leads to poorer outcomes through defensive practice.

What is the impact on the GP workforce?

But let’s think strategically. There are lengthening waiting lists in general practice because the number of GPs in practice is plummeting. fewer GPs and more dispersed primary care? Isn’t that cheaper? And it it’s less effective, will anyone know? If we do accept role substitution as a solution to the GP shortage, what was all that training and sacrifice around meeting standards the community developed for general practice for? Why did we make the training and assessment so onerous?

In the UK, introducing multidisciplinary primary care teams did not seem to be effective in reducing hospital admissions, and the evidence for the efficacy of these teams is not clear. While there is no doubt nurses and allied health professionals bring invaluable skills into primary care, the evidence for the best use of multi-disciplinary skills in the Australian context is still evolving.

It may be cheaper in the short term to shrink the GP workforce. The ability to manage the patients no one else will see will drop, but I’m not sure anyone is measuring the metrics that will detect a change. Because trying to develop metrics for truly complex care is hard, and you need us to do it, and the investment in GP research has plummeted.

And I and my colleagues – who weren’t given personal protective equipment (PPE) early in the pandemic, who were told we weren’t frontline workers so we didn’t need vaccination early like hospital kitchen staff, but were frontline workers when we were needed to give vaccinations, who sourced our masks from patients with a sewing machine, who were vilified for protecting the immunosuppressed Granny in our waiting rooms by redirecting people with potential COVID-19 to the respiratory clinics we set up, who are being assaulted regularly in our clinics – we know we are expendable.

I’ve taught generations of doctors, written policy briefs, sat on committees, done GP research, worried myself sick about suicidal junior doctors, mostly unpaid, definitely undervalued. We used to attract 50% of the junior doctor workforce into general practice. Now it is 13%. We are expecting to be 11 000 full time GPs short by 2030. On any metric, this is a poor outcome.

Next steps

For decades I have defended my profession and my patients against policies that will disadvantage the most vulnerable. I have questioned policies that give more “consumer choice” for those with the literacy, health literacy and resources to access it, while reducing equity. I have taught professionalism, ethics and patient centred, value-based healthcare.

But none of us can endure persistent vitriol. It is easy to scapegoat doctors, and hang on to the idea that we are greedy, self-serving grubs. But the consequence is losing thousands of GPs from a shrinking workforce. Like many of my colleagues, I am just too bruised and battered to fight for my patients while I’m being accused of incompetence, callousness and fraud; to have my motives questioned; to challenge the narrative that I’m a greedy elitist with a hidden fortune fleecing the public for my own gain.

After 30 years of dedicated service, I no longer trust political assurances, or the expression of good will. The sad thing is that the system is behaving the way it was designed to do. Intentional or not, the demise of good general practice has been predictable for decades.

The question remaining is whether the community is happy to let it go.

Louise Stone is a GP with clinical, research, teaching and policy expertise in mental health. She is Associate Professor in the Social Foundations of Medicine group at the Australian National University Medical School, and works in youth health.

This piece was originally published at MJA Insight.