Women and girls account for half the population, yet most medical research is conducted in males.

Women and girls account for 50% of the population, yet most health and physiology research is conducted in males.

This is especially true for fundamental research (which builds knowledge but doesn’t have an application yet) and pre-clinical (animal) research. These types of research often only focus on male humans, animals and even cells.

In our discipline of exercise physiology, 6% of research studies include female-only participant groups.

So why do so many scientists seem oblivious to the existence of half of the world’s population?

Read more: Equal but not the same: a male bias reigns in medical research

Females, women, trans men and non-binary folks

Firstly, it’s important to understand key terminology in society and research. As referred to throughout this article, “male” and “female” are categories of sex, defined by a set of biological attributes associated with physical and physiological characteristics.

In comparison, “men”, “women” and “non-binary people” are categories of gender: a societal construct that encompasses behaviours, power relationships, roles and identities.

Here we discuss research on specific sexes, but further consideration of gender-diverse groups, such as transgender people, also remains a gap in science.

Why aren’t females studied?

The main reasoning is that females are a more “complicated” model organism than males.

The physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle add a whole lot of complexities when it comes to understanding how the body may respond to an external stimulus, such as taking a drug or performing a specific type of exercise.

Some females use contraception, and those who do use different types. This adds to the variability between them.

Females also undergo menopause around the age of 50, another physiological change that fundamentally impacts the way the body functions and adapts.

Even when research with females is performed properly, the findings may not apply to all females. This includes whether a female individual is cisgender or gender nonconforming.

Altogether, this makes female research more time-consuming and expensive — and research is nearly always limited by time and money.

Does it really matter?

Yes, because males and females are physiologically different.

This does not only involve visually obvious differences (the so-called primary sex characteristics, such as body shape or genitals), but also a whole range of hidden differences in hormones and genetics.

There’s also emerging evidence from our research team that sex differences impact epigenetics: how your behaviours and environment affect the expression of your genes.

Conducting health and physiology research in males exclusively disregards these differences. So our knowledge of the human body, which is mostly inferred from what is observed in males, may not always hold true for females.

Some diseases, such as cardiovascular (heart) disease, present differently in males and females.

Read more: Women who have heart attacks receive poorer care than men

Males and females may also metabolise drugs in a different way, meaning they may need different quantities or formulations. These drugs can have sex-specific side effects.

This may have major consequences in the way we treat diseases or the preferred drugs we use in the clinic.

Take COVID-19, for example. The severity and death rates of COVID-19 are higher in males than females. Sex differences in immunity and hormonal pathways may explain this, therefore researchers are advocating for sex-specific research to aid viral treatment.

We’re finally starting to see some change

No matter the cost or added complexity, research should be for everyone and apply to everyone. International medical research bodies are now starting to acknowledge this.

A March 2021 statement from the Endocrine Society, the international body for doctors and researchers who study hormones and treat associated problems, recognises:

Before mechanisms behind sex differences in physiology and disease can be elucidated, a fundamental understanding of sex differences that exist at baseline, is needed.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest medical research board in the United States, recently called for researchers to account for “sex as a biological variable”.

Unless a strong case can be made to study only one sex, studying both sexes is now a requirement to receive NIH research funding.

The Australian equivalent, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), indirectly recommends the collection and analysis of sex-specific data in animals and humans.

However the inclusion of both sexes is not yet a requirement to receive funding in Australia.

But researchers can start now

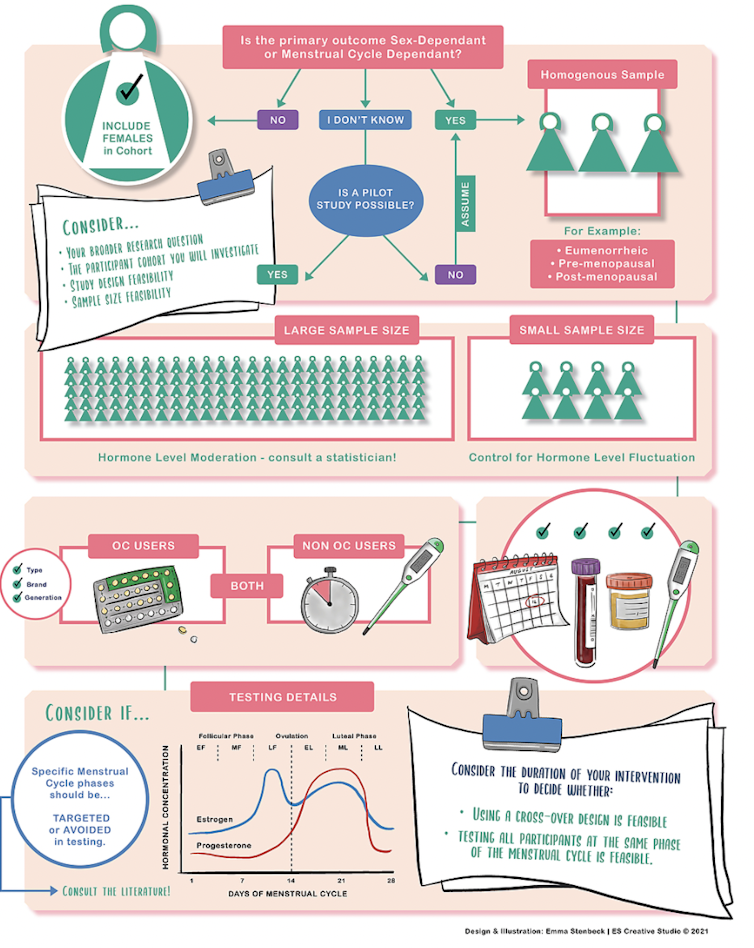

Because sex matters, we created a freely available infographic based on our research that aims at making female health and physiology research easier to design.

It presents as a simple flow through diagram that researchers can use before starting their project and prompts them to consider questions such as:

- is the phenomenon I am investigating influenced by female hormones?

- should all females in my cohort use the same contraception?

- on which day of the menstrual cycle should I test my participants for the most reliable result?

Depending on the answers, our infographic proposes strategies (that can be practical — such as who to recruit and when — or statistical) to design research that takes into account the complexity of the female body.

It’s easy to follow and accessible to all. And, while initially designed for exercise physiology research, it can be applied to any type of female health and physiology research.

Read more: Medicine’s gender revolution: how women stopped being treated as ‘small men’

Based on our infographics, we designed a female-only, four-year research project to map the process of muscle ageing in females. Females live longer than males but, paradoxically, are more susceptible to some of the consequences of ageing. Despite lots of ageing research in males, we still know very little about the female-specific characteristics at play.

So yes, the future is female — so is our research. And we hope to inspire health and physiology researchers all over the world to do the same.

Severine Lamon, associate professor, nutrition and exercise physiology, Deakin University

Olivia Knowles, PhD candidate, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.