Cultural conditioning and social pressures are driving a surge in demand from women for a mostly unnecessary cosmetic procedure

A 16-year old who lives in Sydney is so distressed by how her vulva looks she tries to take a pair of scissors to her labia. Another goes through puberty petrified that someone will spot her longer-than-average labia minora through her swimwear. She suffers emotional abuse from a partner who calls her genitals “weird”. She undergoes labiaplasty aged 23 and is satisfied with the result; it’s a relief to finally feel comfortable in her own skin, she says.

Girls as young as 11 are now seeking genital cosmetic surgery in Australia, despite their genitals being comfortably within the bounds of what is considered normal by gynaecologists.

At the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, the average age of females presenting with concerns about their genital appearance is 14.5 years.

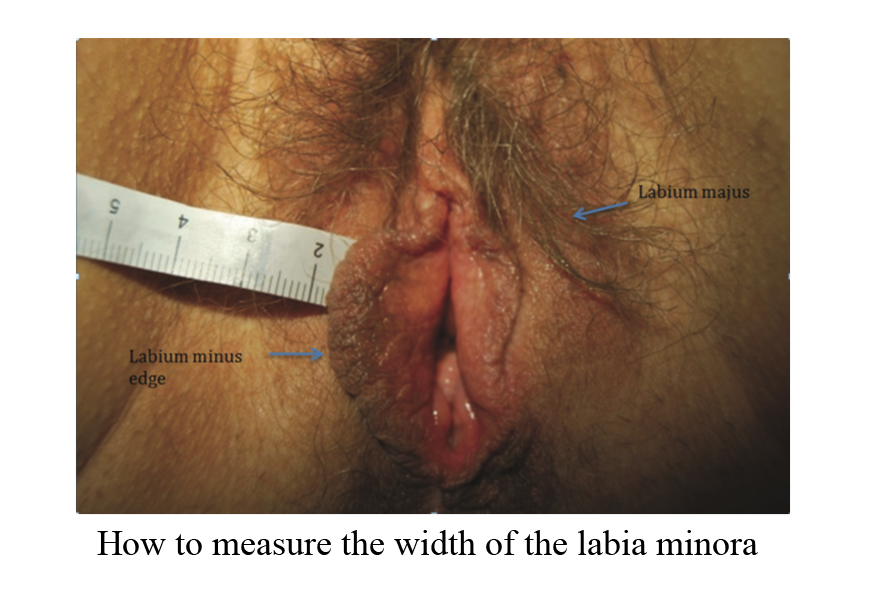

Surgical removal of labia minora tissue is generally only medically indicated, and Medicare rebatable, in women who suffer significant functional impairment due to labia that extend more than 8cm below the opening of the vagina while the patient is in a standing position.

But, of 46 patients seen by the Royal Children’s Hospital for perceived genital issues, only three women had labia more than 5cm in width. Most girls with anxieties about their genital appearance were anatomically normal.

In fact, there appears to be absolutely no correlation between labia minora width and the desire for surgical reduction; even women with labia minora as small as 1cm requested surgery in a UK study.

This worrying trend of women with normal genitals seeking surgery has been seen around the globe. Labiaplasty is now the fourth most popular cosmetic procedure, after liposuction, breast augmentation and rhinoplasty.

In Australia, 1,588 women had a blade taken to their genitals in 2013, representing a 140% increase in labiaplasties since 2001. The UK saw a five-fold increase over a decade, while rates of labiaplasty grew by 44% in one year alone in the US.

Disturbingly, labiaplasty is medico-legally indistinguishable from female genital mutilation, which is now illegal in Australia even for consenting adults.

That doesn’t stop some of those profiting from labiaplasty from shaming women into becoming clients. Do a Google search and you’ll find that the “before” images on labiaplasty provider websites actually pathologise the genital anatomy of up to three-quarters of the world’s female population, which is, no doubt, good for business.

Many websites also pair images of healthy labia with words like “unattractive” and suggest that “excess” labiae tissue is in need of “correction” to create labia that are “smaller and nicer”.

A review of five studies looking at labiaplasty advertisements found that vulva diversity was pathologised in cyberspace through disparaging, hurtful language.

“Innie” labia minora are currently considered fashionable (at least in Western culture), but this passing trend is highly problematic because an estimated 73% of women don’t naturally fit this classification.

The vast majority of women have “outie” labia minora and/or clitoral hoods that extend beyond the labia majora.

The average width of the labium minus is 1.38cm, but it ranges from 1mm to 6.1cm. Around half of women have asymmetrical labia minora.

The variation in size, shape, texture and colour of female genitals is so enormous that Gynodiversity, a Tumblr project that has collected hundreds of images of vulvas, has published a 30-page report just documenting the differences.

Gynodiversity’s analysis reveals that few women (only around 27%) naturally have flat genitals that happen to conform with the “after” images promoted by cosmetic surgeons.

Gynodiversity was started in 2012 as a a self-funded crowdsourcing project run by Vicky Pryce-Henderson, a UK-based physical therapist, and her husband, Leland. “[The project] actually started because of my own insecurities,” said Ms Pryce-Henderson. It now has one of the largest collection of photographs of real vulvas in the world.

“After ‘processing’ and placing a many hundreds of contributions in the various panels, Leland started to notice patterns and recurring traits regarding the genital appearance of all these women,” said Ms Pryce-Henderson. “In an effort to map and describe these patterns, he created the classification as presented in our paper. We did receive some helpful input from a retired GP.”

Print censorship laws in Australia, prohibit “genital emphasis” in pornography, art, surgical advertisements, medical images, and the mainstream media. This creates a distorted media environment where almost every depiction of female genitals is simplified to resemble a Barbie doll or pre-pubescent girl. The genital anatomy of the majority of women is not represented at all.

In everyday life female genitals are usually so well hidden by clothes or pubic hair, that many heterosexual women have no idea what other women’s vulvas look like. Women need to use a mirror just to look at their own.

When a woman is kept in the dark about what real female genitals usually look like, a casual remark from a sexual partner can easily inflame private anxieties and cement a decision to have parts of the vulva permanently removed.

GPs TO THE RESCUE?

When Dr Magdalena Simonis was first confronted by a young teenager asking for a labiaplasty a few years ago, she was caught off guard. “I didn’t know anything about it at the time,” says Dr Simonis, a GP and research fellow at The University of Melbourne.

Dr Simonis felt that something needed to be done to counter the online bias that was influencing young minds, and thus the Labia Library was born. Created in partnership with Women’s Health Victoria, the Labia Library is a website that contains 40 images of real vulvas. “I like to bring these images up for my patients when I have these discussions [about labiaplasty],” says Dr Simonis.

Since its creation in 2013, nearly six million people have visited the site from around the world, with an average of 3,000 to 5,000 visitors per day.

“The majority of users are women and girls who are concerned about their genitals and are really just looking for a point of reference and some basic information,” says Dr Amy Webster (PhD), senior policy and health promotion officer at Women’s Health Victoria.

For a project that was funded through a one-off grant of $10,000, it’s had an astonishing impact. A recent survey of 3,000 users reveals that many women harbour life-long anxieties that can be instantly resolved by a quick glance at the vulva gallery.

“I am 38 and I have thought for a long time that I need labia surgery it’s a relief to see many like me,” one woman wrote.

“Thank you for taking my worst insecurity and making me feel normal.”

Another woman responded: “I’m 66 years old and this is the first time I’ve had this information. Always thought my bits didn’t look normal and never had the courage to ask. Now I know they are just fine.”

Even seemingly small interventions can reduce anxiety, and may stop women from resorting to surgery, says Dr Simonis.

“At first pap smear or when examining a woman for the first time I will always comment, ‘Everything looks entirely normal. The response is always relief, even when I wasn’t aware there was any anxiety beforehand.”

GPs are now being inundated by requests for labiaplasty; a survey of around 400 GPs found that nearly half had patients asking for female genital cosmetic surgery.

More than half of of GPs suspected psychological disturbances, such as depression, anxiety, relationship difficulties and body dysmorphic disorder, in patients requesting the procedure.

Alarmingly, 35% of GPs had been asked for the surgery by girls under the age of 18.

One of the reasons that teenagers are so concerned about their genital appearance is because Brazilian waxes are in fashion, says Dr Simonis.

“When you are a little girl you have a slit, a single line,” she says. “Then you go through puberty and you have genital hair. Behind the genital hair the tissue grows. And the appearance when the hair is removed is actually very foreign to the young woman.”

Genital cosmetic surgery should be avoided before the age of 18, says Dr Simonis. Genital anatomy changes dramatically during the teen years, and if women are operated on before full maturity, the outcomes can be very poor.

Guidelines from the Medical Board of Australia recommend mandatory psychological evaluation for women under the age of 18 requesting labiaplasty, and a three-month cooling off period.

The RACGP recommends that GPs refer adult women requesting labiaplasty to a gynaecologist for a second opinion. Where mental health issues exist, GPs should refer to counselling first.

Labiaplasty is not a risk-free procedure. The RACGP guidelines’ list of complications includes: bleeding, wound dehiscence, infection, scarring, sensorineural complications, dyspareunia, removal of too much tissue, pain, tearing of scar tissue during childbirth, psychological distress, and reduced lubrication.

Reports from cosmetic surgeons indicate that most women are satisfied with their labiaplasty, however, none of these findings are published, and there is a clear conflict of interest in surgeons carrying out these surveys.

There is a complete absence of research on long-term outcomes.

The trimming of the labia minora removes some of the most sensitive and nerve-dense tissue women have. “And it’s not being focused on enough,” says Dr Simonis.

“Women don’t fully understand when they are having this done that reduction in surface area might actually have an impact on their responsiveness and pleasure later on in life when they are post-menopausal, when there is genital atrophy.”

PSYCHOLOGICAL REMEDIES

Women often say they are concerned about having “normal” genitals, but what many women really fear is being considered ugly, says psychologist Dr Gemma Sharp.

So, when a GP assures a woman that her genitals are statistically normal, that might not be enough to stop her pursuing surgery.

Surgery addresses one aspect of the problem, but it leaves some women feeling disappointed.

In a prospective, controlled study of around 50 women, the women who underwent labiaplasty felt better about their genital appearance after six months. However, labiaplasty did not lift their self-esteem, life satisfaction, or sexual confidence.

Dr Sharp invites GPs to try a slightly different approach when counselling women about genital appearance concerns.

Firstly, GPs can validate women’s feelings by letting them know that it’s actually pretty normal to feel self-conscious or unhappy about one’s genital appearance, given all the socio-cultural pressures that women are under, says Dr Sharp.

“And I think it would just be about exploring what their options are besides surgery,” she says.

Dr Sharp’s proposes using a psychological strategy rather than a surgical one. Her team is building a mobile app for self-directed CBT, which helps patients challenge negative thoughts about their body.

“So they are doing the same kinds of exercises that someone would do in therapy but not with the embarrassment of having to go and talk to a psychologist about it,” says Dr Sharp. It’s also a much cheaper intervention than surgery, which costs around $4,000, with a Medicare rebate of just $262.40.

The app will be launched next year under the discreet name, MyMandorla.

“Mandorla is the Italian word for almond,” says Dr Sharp. “The Mandorla is the giver of life, so it’s a bit of a slang term for vagina. But it has a very spiritual connection to it.”

The ultimate aim of therapy is to replace harsh thoughts with helpful ones. But it’s sad, and somewhat absurd, that this intervention is necessary.

“Why do we even get these genital ideals? They make no sense,” says Dr Sharp.

“It’s not even the same the world over. In [Rwanda and Zimbabwe], they attach weights to their labia to make them longer because that’s considered beautiful. A women with larger labia would be super attractive in Africa.”

Dr Maggie Kirkman, a psychologist and senior research fellow at Monash University, has concerns about the emphasis on diagnosing individual psychopathology in women seeking labiaplasty.

“I’m not denying that some women have huge problems with body dysmorphia but, as far as I can gather, most of the women are just trying to do what they see as the right thing, being autonomous, making choices and making the best of themselves, which is a different thing,” says Dr Kirkman.

GPs can try to jolt women out of their cultural conditioning by pointing out that women are under extreme social pressure to modify their bodies, sometimes in painful and dangerous ways, which is sexist and unfair.

A few men undergo penis enlargement every year in Australia, a procedure that costs around $10,000.

“[But] you will find very few men chopping off bits of their penises and scrotum because they are afraid of what women will think of them,” says Dr Kirkman.

“Women will say things like, ‘It’s uncomfortable when I ride a bicycle or you can see my labia minora in tight clothes’. “You could imagine, if that happened to men, they wouldn’t say, ‘Oh, I’ll just chop off my balls’, they would say, ‘I will modify my bicycle seat’ or ‘I will wear different kinds of shorts’.”

PLASTIC SURGEONS’ VIEW

The official view from the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons is that surgeons should say ‘no’ to patients with significant mental health problems asking for labiaplasty who have not undergone a psychological assessment.

“I think we do need to be careful about who this operation is offered to and what their motivations are for seeking this surgery,” says Associate Professor Gazi Hussain, the vice president of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Plastic surgeons will usually arrange two separate consultations to talk through why a patient wants labiaplasty, with a cooling off period of ten days before surgery, says Professor Hussain.

Patients are shown before and after images of labiaplasty to give them a realistic idea of what labia normally look like, as well as what they can realistically expect from surgery.

When labiaplasty is performed correctly by trained surgeons, there are usually no significant long term problems, says Professor Hussain.

But it’s currently legal for any doctor with a basic medical degree to perform cosmetic surgery in Australia, so botched labiaplasties are still common.

Patients are often embarrassed at the consultation and don’t feel confident to question the training and expertise of the doctor, says Professor Mark Ashton, the president of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons.

He urges patients to do their research beforehand by checking whether the labiaplasty provider is registered as a doctor with AHPRA, and is a member of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

“The most common mistake is that the patients have the procedure done under local anaesthetic in the doctors’ rooms,” says Professor Ashton.

“In some cases I have seen the entire labia amputated to less than 5% labia left. This is very difficult to treat. We have seen multiple patients where this has occurred.”

Victoria, Queensland and NSW have recently banned labiaplasty outside of fully licensed and accredited facilities.

Patients often don’t complain about cosmetic surgery procedures that have gone horribly wrong because they feel they have brought the suffering on themselves, says Professor Hussain.

The Health Care Complaints Commission in NSW launched an inquiry into cosmetic health service complaints earlier this year to try to address the problem of under-reporting.

For such a poorly regulated market, there’s little trace of labiaplasty complaints or litigation. The Medical Republic emailed medical complaints bodies in every state in an attempt to uncover complaints statistics. Queensland’s Office of the Health Ombudsman reported four labiaplasty complaints since 2014.

The only other state body that provided numbers was NT’s Health and Community Services Complaints Commission, which reported zero complaints about labiaplasty.

The Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons says that no complaints have been made against any of its members in relation to labiaplasty.

The only example of an Australian woman speaking out about a botched labiaplasty in the media is that of Carrie, a 25-year old from Queensland, who told the ABC in 2015 that her life had been a living hell after an untrained GP performed a labiaplasty that stitched over her urethra, disrupting the passage of urine.

Carrie ended up in hospital with a haematoma, and, three years on, she was still seeking treatment to correct the surgery.

“Hopefully, this helps someone to not make the same mistake that I did,” she said.

“I just don’t want this to happen to anyone else.”

Image credits:

1) Reproduced with permission from Gynodiversity. See the full report here: bit.ly/2z0TZLP

2) Reproduced with permission from the Labia Libraryand Women’s Health Victoria

3) Published with permission from Annemette W. Lykkebo