DoHAC’s 12% increase in spend on Medicare, aged care and the PBS is our biggest health investment in a decade, but is it sellable to the voters?

Who’d want to be an incumbent government after this week’s US election result?

Post-pandemic and amid a couple of significant ongoing hot wars in Europe and the Middle East most western governments are struggling to tame cost-of-living pressures, largely because those costs aren’t within their ability to control.

Voters don’t care.

The release of this week’s Department of Health and Aged Care annual report should prompt both the government and the opposition to think a lot more carefully about how they are going to treat healthcare in the upcoming election.

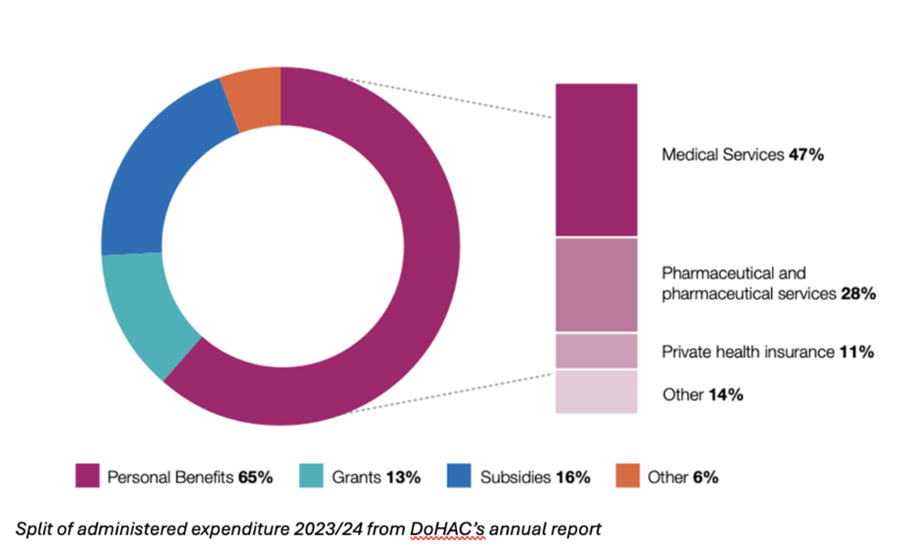

The report reveals that our second largest spending government department increased its administered expenditure from $93.6 billion to $104 .5 billion (by $9.825 billion), an 11.6% increase on the previous year’s spending which is more than any one single year in the last decade.

In the current febrile cost-of-living hyped-up environment, will the electorate reward or punish the government for increasing its investment in healthcare in one year in net terms by more than in any year of the last decade? And by more than any other federal government administered sector?

The reported result largely isn’t a surprise.

Most of expenditure was planned in the budget. The department spent just $1.182 billion more than it budgeted, which is only a 1.1% overspend.

By comparison, our largest spending government agency, Services Australia, which includes the significant impost of the NDIS, increased its administered expenditure by 9.8% from $217.7 billion to $239.7 billion this year.

It means that healthcare appears to be the current government’s biggest policy spending gamble in political terms, something that doesn’t seem immediately obvious if you’re reading daily newspapers or watching network TV news.

It all might make the federal health minister Mark Butler one of the most important salespeople on the government’s front bench going into next year’s election, depending, of course, on how the government wants to position and sell its significant healthcare spend.

Although we are still very early into the election campaign cycle you so far don’t get the feeling that health is one of the current government’s major election sales pitches.

That might be because the government is still trying to weigh up how the opposition, and potentially the electorate, will view the investment against seemingly inevitable attacks about government spending driving our cost-of-living crisis.

Will the opposition somehow try to frame this spend as reckless and a significant contributor to the cost-of-living in Australia? Which of course it largely isn’t.

That would surely be risky as well: “Look at all this money that this reckless bunch has spent on you so you can get to see a GP more quickly, pay less when you do, access an ED, have more access to aged care and pay less for your drugs … it’s causing the cost of Corn Flakes to skyrocket.”

No matter which way the opposition chooses to play the spend, our current government’s significant commitment to healthcare could, if it played its cards the right way, put the sector on the map as a major swing factor in the upcoming election.

One thing the US election may have taught our government is that you want to get on the front foot early with solid and electorate-friendly signature policies. Make them simple to understand, relatable to everyday life, and sell them hard. Healthcare access and cost feels ripe for that given the investment this government has now made.

Healthcare wasn’t one of those policies in the US, but it could easily be here in Australia given the series of crises gripping the sector – GP access, ED access, cost of seeing a GP and so on.

Given just how much the federal government has invested why wouldn’t they get on the front foot and try to make it one?

The two largest elements of investment are in personal benefits – mostly Medicare benefits (including bulk-billing incentives), PBS (drug subsidies) and private health insurance – and residential aged care subsidies.

Both might have reasonable election optics if sold the right way, although a key problem could be the perceived gap between investment and what is happening at the coalface.

In other words, is the electorate seeing any shift in any of the key issues it faces in healthcare today as a result of this investment?

Related

As far as cost to see a GP is concerned, bulk-billing stats indicate only a slowdown in the trend to private billing, not a reversal, so the pitch can’t be “it’s better” – yet.

ED and GP access also remain largely fraught issues, so the pitch might end up coming down to investment.

The largest single element in both net and relative terms is the investment in residential aged care places for senior Australians of an additional $5 billion, a 30% increase on the previous year.

The increase to personal benefits in the year (Medicare including bulk billing) totalled $4.8 billion and rose in relative terms by 8% in the year.

The other element of spending that increased overall – albeit by only 4% and $480 million – was investment in health research, mental health, first nations health, and aged care quality grants.

Might this detail matter to the electorate in any potential sales pitch?

It likely would.

“Strengthening Medicare” is a much used and increasingly droll tagline that doesn’t mean much to an electorate who largely have never even understood how Medicare has ever worked.

Honing in on the investment made in some of the relatable specifics such as the cost of seeing a GP and GP access might be the better way to go from here.

Read the full DoHAC annual report here.