The numbers suggest not, but there are still ways to do it more safely.

New South Wales Premier Dominic Perrottet is driving a push to reduce isolation requirements for people who test positive for covid from seven to five days. It’s slated for discussion at tomorrow’s National Cabinet meeting, with Perrottet urging a consistent approach across all states and territories.

Others, including Health Services Union president Gerard Hayes, have called for the isolation requirement to be scrapped altogether, and instead, urging people to stay at home if they’re infectious.

So what will states be weighing up? Here’s what the available evidence says.

How many infectious people are in isolation?

Not everyone tests for infection, even if they suspect they might have covid. Many people won’t know to test if they have mild or no symptoms and are unaware they’ve been exposed.

Our latest serosurvey data, which tests for antibodies in blood donations, suggests around one quarter of the population has had a covid infection in the three months up to June. That equates to about 6.8 million people.

But only 2.7 million infections were reported in that time period. And these will include cases where the same people had multiple infections. Therefore, it’s likely four to five million infections went untested or unreported.

Some people who don’t test or report a positive result might still isolate. At the same time, some who do report their infections may not isolate properly.

This isn’t just about people being compliant or not. It also reflects the large number of asymptomatic infections, as well as other respiratory symptoms that can mask covid.

A survey of 210 people in the United States found only 44% were aware they’d had a recent Omicron infection. Among those who weren’t aware, 10% reported having had any symptoms which they mostly put down to a common cold or other non–covid infection.

For those who do test and isolate, it’s important to also ask how far into their infections they are when they start isolating.

Isolation starts with a positive test which, in most cases, follows the onset of symptoms, possibly by a day or two. If someone knows they have been a close contact of a case, they may be on the lookout for signs of infection, knowing they have been exposed. Others may miss the signs initially if they commonly experience respiratory symptoms from other causes.

How long are we infectious?

A UK study in The Lancet of 57 people who developed covid while under daily monitoring tracked participants’ infectious viral load and symptoms.

It found half had an infectious period that lasted up to five days. One-quarter had an infectious period that lasted three days or less. Another quarter were infectious beyond seven days – though with much lower levels of live viral shedding late in their infection.

However, the infections in this study were the Delta variant, so may overstate the duration of infectious periods nowadays.

A JAMA review of the time from exposure to symptoms found the mean incubation period has shortened with each new variant. It went from an average of 5 days for infections caused by Alpha, to 4.4 days for Delta, and 3.4 days for Omicron variant. Omicron may therefore also have a shorter overall infectious period on average than Delta.

In the Lancet study, vaccinated people also had a faster decline in their infectious viral load than those not fully vaccinated. The high rates of vaccination and hybrid immunity in Australia could also be shortening the time we are infectious compared to Delta infections.

The Lancet study also reported one-quarter of people shed infectious virus before symptoms started. Interestingly, it found RATs had the lowest sensitivity during the viral growth phase and viral load peak. This means people were less likely to have a positive result in the first days of their most infectious period.

So some people will not test positive, and therefore not isolate, until one or two days into their infections, even if they’re testing with a RAT every day.

Overall, when you sum up the infectious time for those who do not isolate, and the days before isolation for those who do, people with covid spend more time infectious in the community than they do in isolation. And this includes the time they are at their most infectious.

So, how many exposure days are prevented by current isolation rules?

It’s impossible to know, but based on the above, at most it would be around one quarter, and will probably be much lower than that.

The question, then, is whether reducing isolation by two days towards the tail of the infectious period when infectious viral loads are low will have an impact.

This is unlikely, and that has been the experience overseas, probably because this is a marginal change to a risk-mitigation strategy that can only be partially effective at this stage in the pandemic.

However, there are ways to make the transition from seven to five days safer. This includes:

- requiring acute symptoms experienced in the initial stage of the covid infection to have resolved before they end isolation, especially fever

- using negative RAT tests to allow people with a persistent cough or other lingering symptoms that may not be associated with an active infection to leave isolation

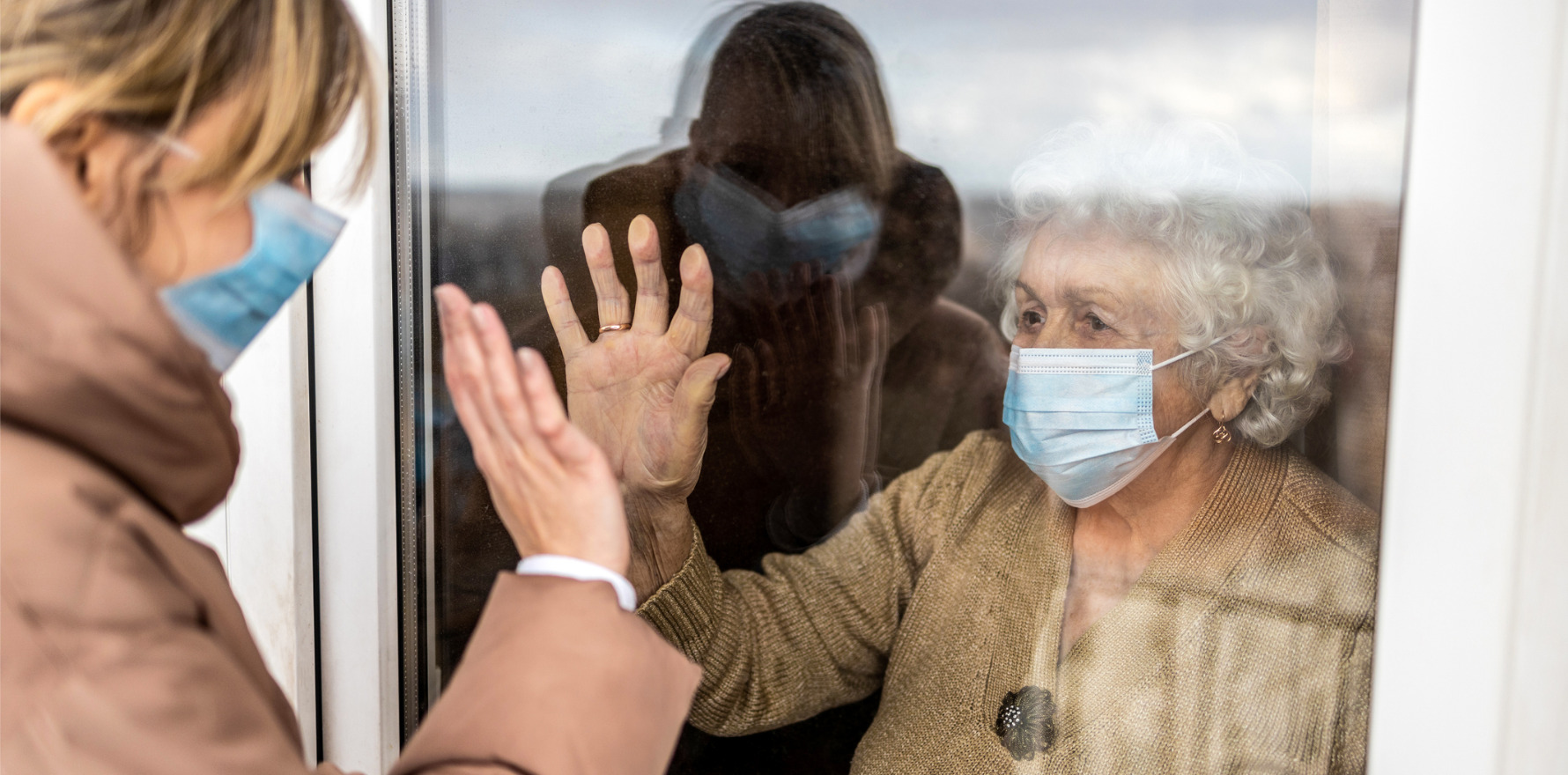

- screening workers from high-risk settings such as health care and aged care before they return to work

- providing clear information on the infection risk to others in the week following isolation, and how to minimise risk.

Whether we take half steps away from isolation or a large leap, the small risk that people may still be infectious enough to pass the virus on to others on leaving isolation – whether that’s at five or seven days – needs to be managed.

It will always be important to wear well-fitted masks, preferably respirators, when around others and avoid people with compromised immune systems for those first two weeks after a covid infection begins when you may still be shedding live virus.

Catherine Bennett is the Chair in Epidemiology, Deakin University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.