“She goes down quickly with a breastfeed at 7pm, but from midnight she is awake every hour or more. Often it takes up to an hour to get her back to sleep … I can’t keep going like this!” This parent describes a baby with disrupted sleep patterns. Her little one’s circadian rhythm is poorly […]

“She goes down quickly with a breastfeed at 7pm, but from midnight she is awake every hour or more. Often it takes up to an hour to get her back to sleep … I can’t keep going like this!”

This parent describes a baby with disrupted sleep patterns. Her little one’s circadian rhythm is poorly aligned with parental circadian rhythms and with real time. That is, her baby is waking excessively, more often than we’d expect with developmentally normal night waking.

(Editor’s note: This article was published in The Medical Republic print magazine on 5 April and online on 7 April. A fact box that contained production errors has been removed from the online version.)

Even if this is the mother of a newborn coping with the circadian immaturity of the first weeks of life, she will benefit from education about how to support the speedy maturation of her baby’s circadian clock over the coming week or two, for the sake of her own and her family’s well-being.

Many parents are concerned about their baby’s sleep.

In a 2014 Victorian study, 38% of 781 recruited mothers reported infant sleep problems at four weeks of age. (This randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the program Baby Business, which incorporates “sleep training” strategies, went on to show that it did not prevent infant sleep and crying problems.)1 In a cohort study of 5,700 Finnish children, 40% of parents of eight-month-olds were concerned about their baby’s sleep.2

Disrupted infant sleep patterns can increase the risk of mood disorders in both mothers and fathers,3-5 and may set psychosocially or biologically vulnerable infants and their families on trajectories of stress and distress, with long-term impacts.6 It’s important to make time for a long or prolonged consultation, preferably with both parents if possible, perhaps by making adjacent parent-child appointments.

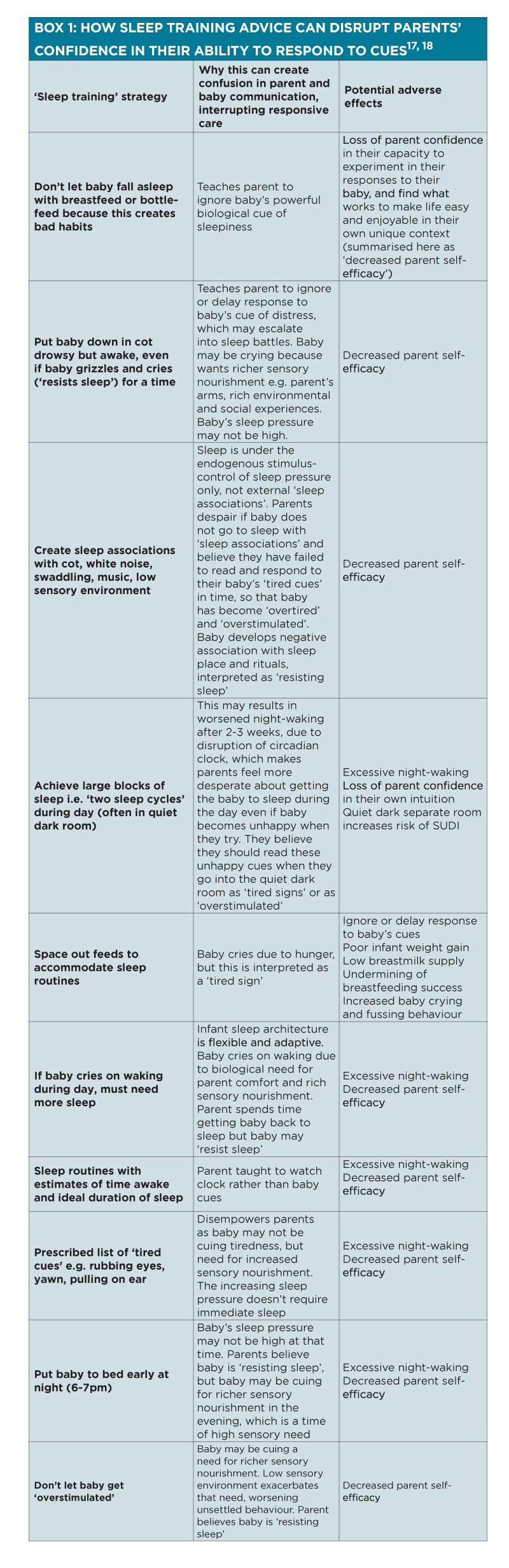

Parents’ high levels of concern about baby sleep occurs in the context of the societally dominant “sleep training”’ philosophy, which parents are advised will prevent sleep problems.

They receive this advice even though sleep training strategies do not decrease night-waking,7-11 and though sleep training has been linked with increased parental anxiety and less responsive parenting. (See box 1)12-18

It takes skill to address unhelpful beliefs without further undermining parental confidence, and you may prefer to refer your patient to an appropriately qualified practitioner for face-to-face or telehealth assistance. You can also direct patients to self-help online as back-up.

But parents trust you as their GP. Here are the basic steps of the evidence-based Neuroprotective Developmental Care approach to infant sleep – here and also in the next article, Hey, baby! How can I help you wake less in the night? This method was first published as the Possums Sleep Program, and is also being trialled in the UK as Sleep, Baby and You.19-23

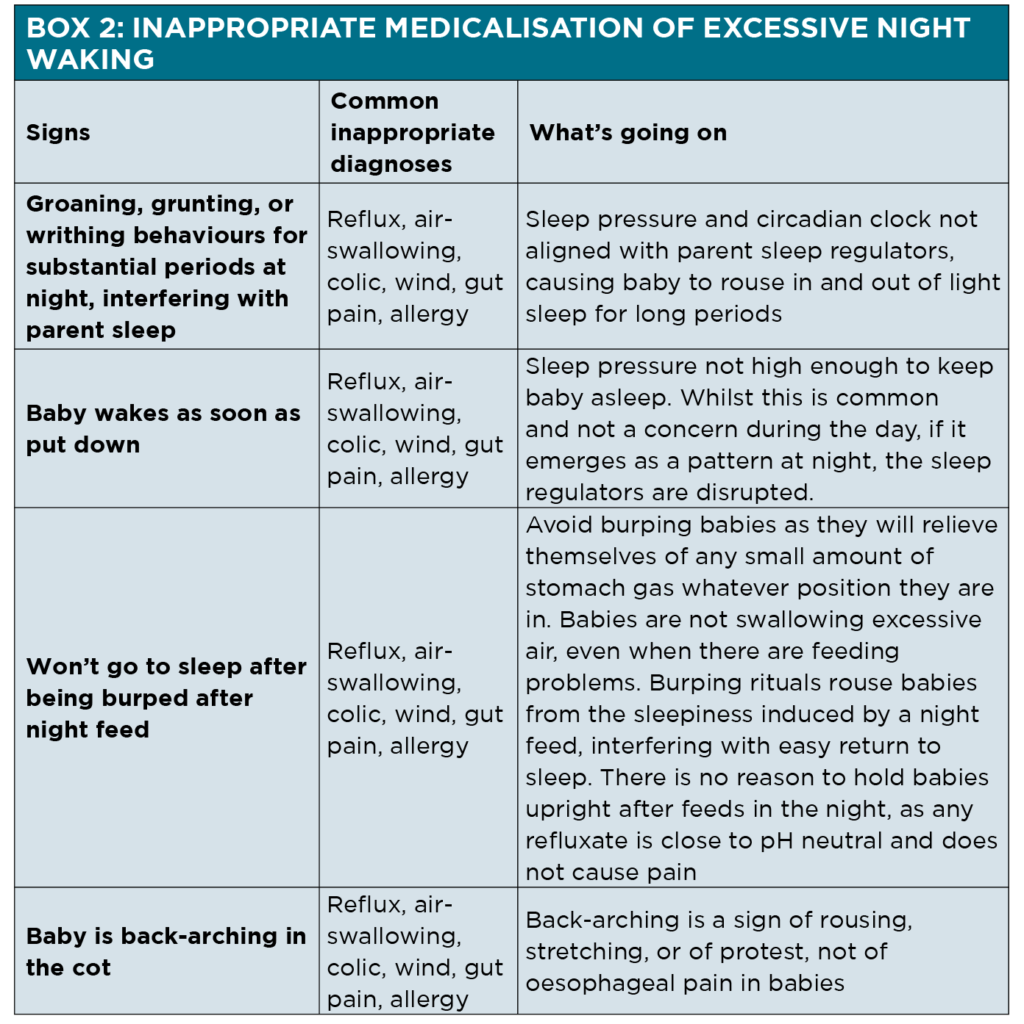

Firstly, take a medical history of both the primary carer and the baby. You may decide it is appropriate to screen for postnatal depression. An unwell baby, with a respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection, for example, might be unsettled in the night. A hungry newborn with breastmilk transfer problems might also wake excessively. Disrupted infant sleep patterns are often inappropriately medicalised. (See box 2)

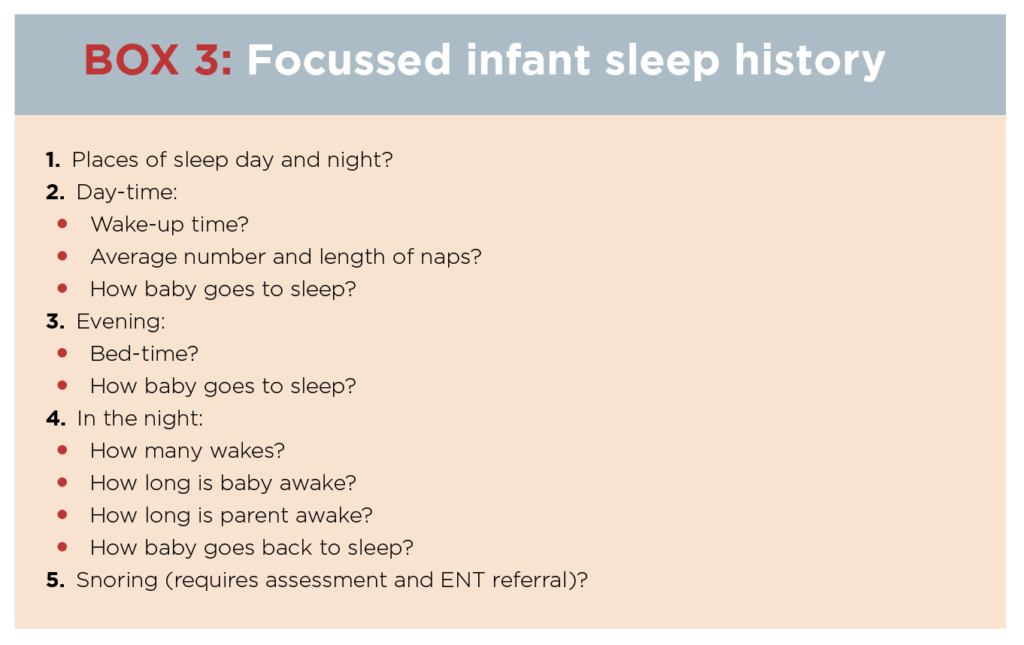

Next, take a focussed sleep history. (See box 3) Hearing parents’ sleep stories with empathy and acknowledging that they are doing a remarkable job meeting their baby’s needs despite their own sleep deprivation is in itself a therapeutic intervention.

I explain the assessment I’ve made, using words like: “Luckily, your little one is not experiencing a problem, since she is getting all the sleep she needs overall. Her needs for secure emotional attachment are being met quite wonderfully, and she is thriving! However, her sleep patterns are severely disrupted. (If the baby is under six weeks of age, I might say: her sleep patterns have not yet matured to be in sync with her parents’ sleep needs and the real world). I agree this situation is simply no longer sustainable. But if you experiment with some new ideas over the next one to two weeks, which we will discuss, I think it’s likely that your nights will become much more manageable, and the days more enjoyable.”

Then, I educate parents about normal infant sleep, drawing on sleep science and neuroscience.1

You might start with the following.

“I hate to say it, but it is developmentally normal for babies to wake up every couple of hours in the first year of life, even into toddlerhood.2, 24-27

“What’s important is that everyone gets back to sleep quickly. You might be comforted to hear that a new Australian study confirms what we thought: that breastfeeding women have as much sleep overall as those whose babies are taking formula.28, 29 Your little one, though, has excessive night waking, which is utterly exhausting and unmanageable for any family. Excessive night-waking occurs when there are regular patterns of waking every hour or more throughout the night, or when the baby is awake and unable to settle back to sleep for substantial blocks of time during the night.”

The following key discussion points are an essential part of parent infant sleep education when dealing with excessive night-waking. Remember that daytime sleep shapes night-time sleep patterns over time. Baby sleep needs are highly biologically variable. We can’t “teach our baby to sleep”, the way you might hear.

Low sleep need babies don’t have poorer developmental outcomes.

There are two biological sleep regulators which control infant and adult sleep, the circadian clock and the sleep-wake homeostat, which controls sleep pressure.

Babies often dial up inside the house because of their powerful biological need for rich and changing environmental experience.

Trying to teach babies to sleep for long periods during the day gradually disrupts the circadian clock, causing excessive night-waking. Putting babies down in quiet dark rooms away from you during the day will do the same.

Internationally, infants often go to bed closer to parent bed-time.

Baby sleep needs decrease throughout the first year of life. (For example, I don’t use the concept of the four-month sleep regression. Disrupted sleep patterns which emerge at this age are likely to result from parents expecting the baby to be in a sleep situation for the same length of time he needed when he was littler, but his sleep needs have decreased. Over a few weeks, this mismatch results in disruption to the baby’s circadian clock and increased night waking.)

It takes one or two weeks to re-set disrupted night-time sleep patterns.

You might find it helpful to use these two scripts which address common concerns parents often raise early in the consultation.

“Baby is not waking excessively because you are breastfeeding to sleep. It’s true that your little one has learnt that the loveliest way to get back to sleep when she wakes is with a breastfeed. This is a gift you’ve given her, not a bad habit you’ve set up! If there comes a time when you need to teach her something new about going back to sleep in the night (by weaning her, for example), we deal with that when the time comes. But for now, we need to deal with the actual cause of her disrupted sleep pattern.

“When a baby begins to rouse in the night, it is normal for that little one to groan and grunt and back arch and writhe, even though she seems to be still asleep. Then she might posset or pass quite a lot of flatulence. Parents naturally think perhaps the baby is waking because of gut pain. But the gut is like a second brain, and highly innervated. As her nervous system rouses, so the gut rouses and activates. I can reassure you that all those loud sounds don’t mean that she is in pain. But she is rousing, and soon you’ll notice she has a little (or big!) gut event. What we need to address is the problem of the excessive rousing in the night, so that you get better sleep. We don’t need to worry about your baby’s gut.”

Developing a management plan for a disrupted infant circadian clock is best framed as steps that parents might experiment with over the next couple of weeks. We will explore how to create this collaborative plan in the next exciting episode of Hey, Baby!

… OK, so maybe I’m overstating the excitement … but I hope you agree that this stuff is important, because it can dramatically improve a parent’s sense of well-being if she or he or they have a baby.19-21, 23

Dr Pamela Douglas is a GP and Medical Director of Possums & Co. www.possumsonline.com, a charity which educates health professionals in the evidence-based Neuroprotective Developmental Care (NDC) or Possums programs, including the Possums Baby and Toddler Sleep Program. If you wish, you can refer to an NDC accredited practitioner. There are lots of free videos and other resources for parents with babies here, and online parent peer support is available for a nominal fee. Pam is an Associate Professor Adjunct with the Maternal Newborn and Families Research Group MHIQ, Griffith University, and Senior Lecturer with the Primary Care Clinical Unit, The University of Queensland. She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying.

Footnotes

This has been delivered as the Possums Baby and Toddler Sleep Program since 2011. We hope you will name it as such with your families, and direct them to the www.possumsonline.com website where there is a great deal of free resource for them, and also the Possums Baby and Toddler Sleep Program and the Possums Parent Hub (PIPPS) available for a nominal fee. Acknowledging the source of this work matters because it helps our charity continue to raise funds for education and research, in the absence of external funding for primary care innovation. We notice some sleep consultants or educators have started to use this work for their own commercial benefit, re-labelling the steps in the program as their own ‘evidence-based approach to infant sleep’. But like all clinical translations of the research, this suite of education and clinical strategies is a unique and integrative primary care interpretation of heterogeneous evidence, first developed and delivered in 2011 and, with Dr Koa Whittingham, first published under the name of the Possums Sleep Program in 2014. It is updated as evidence emerges. Please direct parents to NDC accredited practitioners only, which will be safest for baby and family.

References:

Hiscock H, Cook F, Bayer JK, Le HN, Mensah FK, Cann W, et al. Preventing early infant sleep and crying problems and postnatal depression: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):e346-354.

Paavonen JE, Saarenpaa-Heikkila O, Morales-Munoz I, Virta M, Hakala N, Polkki P, et al. Normal sleep development in infants: findings from two large birth cohorts. Sleep Medicine. 2020;69:145-154.

Henderson JT, Alderdice F, Redshaw M. Factors associated with maternal postpartum fatigue: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):1-9.

Wilson N, Lee JJ, Bei B. Postpartum fatigue and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;246(224-233).

Cook F, Giallo R, Petrovic Z, Coe A, Seymour M, Cann W, et al. Depression and anger in fathers of unsettled infants: a community cohort study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2017;53(2):131-135.

Douglas PS. Pre-emptive intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder: theoretical foundations and clinical translation. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2019:doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2019.00066.

Kempler L, Sharpe L, Miller CB, Bartlett DJ. Do psychosocial sleep interventions improve infant sleep or maternal mood in the postnatal period? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2016;29:15-22.

Douglas P, Hill PS. Behavioural sleep interventions in the first six months of life do not improve outcomes for mothers or infants: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:497–507.

Bryanton J, Beck C, Montelpare W. Postnatal parental education for optimizing infant general health and parent-infant relationships. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(11):CD004068. DOI: 004010.001002/14651858.CD14004068.pub14651854.

NHMRC. Report on the evidence: promoting social and emotional development and wellbeing of infants in pregnancy and the first year of life. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au: Australian Government, 2017.

Sasaki N, Yasuma N, Obikane E, Narita Z. Psycho-educational interventions focused on maternal or infant sleep for pregnant women to prevent the onset of antenatal and postnatal depression: a systematic review. Neuropsychopharmacological Reports. 2020;Dec 19:doi:10.1002/npr1002.12155.

Etherton H, Blunden S, Hauck Y. Discussion of extinction-based behavioral sleep interventions for young children and reasons why parents may find them difficult. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2016;12(11):1535-1543.

Blunden S, Etherton H, Hauck Y. Resistance to Cry Intensive Sleep Intervention in Young Children: Are We Ignoring Children’s Cries or Parental Concerns? Children. 2016;3(2):8.

Whittall H, Kahn M, Pillion M, Gradisar M. Graduated extinction and its barriers for infant sleep problems: an investigation into the experiences of parents. Sleep Medicine. 2019;64:S418.

Morales-Munoz I, Partonen T, Saarenpaa-Heikkila O, Kylliainen A, Polkki P, Porkka-Heiskanen T, et al. The role of parental circadian preference in the onset of sleep difficulties in early childhood. Sleep Medicine. 2018;54:223-230.

Gallaher KGH, Slyepchenko A, Frey BN, Urstad K, Dorheim SK. The role of circadian rhythms in postpartum sleep and mood. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2018;13(3):359-374.

Harries V, Brown A. The association between use of infant parenting books that promote strict routines, and maternal depression, self-efficacy, and parenting confidence. Early Child Development and Care. 2019;189(8):1339-1350.

Harries V, Brown A. The association between baby care books that promote strict care routines and infant feeding, night time care, and maternal-infant interactions. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2019:e12858.

Ball H, Douglas PS, Whittingham K, Kulasinghe K, Hill PS. The Possums Infant Sleep Program: parents’ perspectives on a novel parent-infant sleep intervention in Australia. Sleep Health. 2018;4(6):519-526.

Ball H, Taylor CE, Thomas V, Douglas PS, Sleep Baby and You Working Group. Development and evaluation of ‘Sleep, Baby & You’ – an approach to supporting parental well-being and responsive infant caregiving. Plos One. 2020;15(8): e0237240.

Whittingham K, Douglas PS. Optimising parent-infant sleep from birth to 6 months: a new paradigm. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2014;35:614-623.

Whittingham K, Palmer C, Douglas PS, Creedy DK, Sheffield J. Evaluating the ‘Possums’ health professional training in parent-infant sleep. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2020:doi:10.1002/imhj.21885.

Ozturk M, Boran P, Ersu R, Peker Y. Possums-based parental education for infant sleep: cued care resulting in sustained breastfeeding. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2021:DOI: 10.1007/s00431-00021-03942-00432.

Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, Herbison P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2012;16:213-222.

Teng A, Bartle A, Sadeh A, Mindell J. Infant and toddler sleep in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2011;48:268-273.

Williams JA, Zimmerman FJ, Bell JF. Norms and trends of sleep time among US children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:55-60.

Price A, Brown JE, Bittman M, Wake M, Quach J, Hiscock H. Children’s sleep patterns from 0-9 years: Australian population longitudinal study. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2014;99:119-125.

Smith JP, Forrester RI. Association between breastfeeding and new mothers’ sleep: a unique Australian time use study. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2021;16(7):https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-13020-00347-z.