While it’s frustrating not to see a decrease after tighter restrictions – which some are flouting – Victoria has avoided exponential growth.

Melburnians have now been wearing mandatory face coverings in public for two weeks.

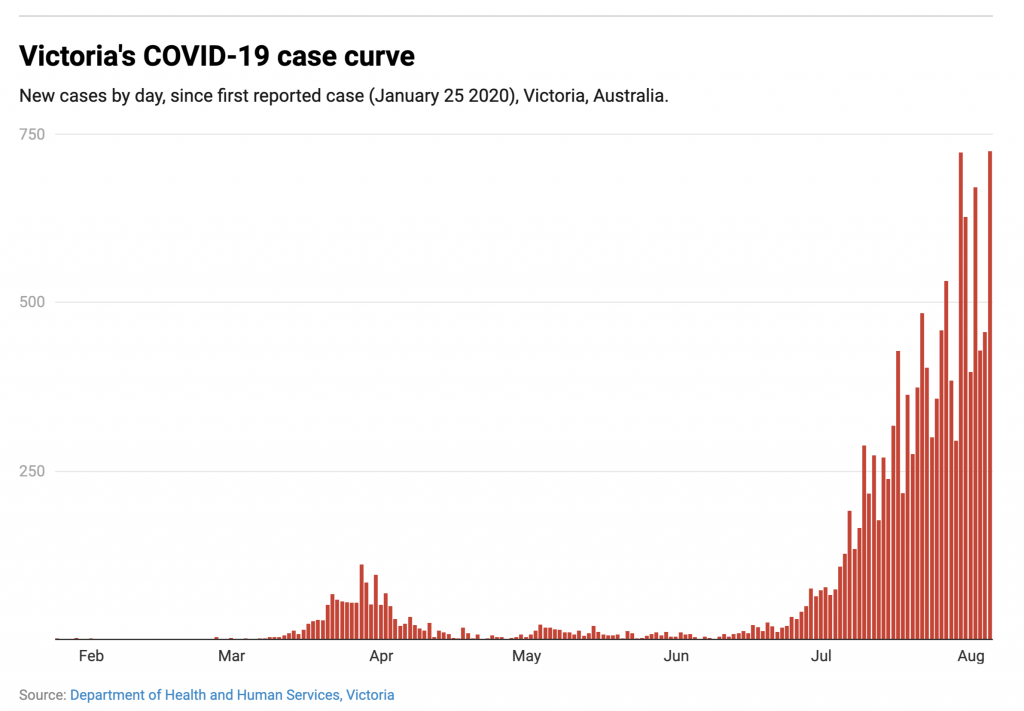

Yet Premier Daniel Andrews yesterday announced another grim milestone in Victoria’s second wave of COVID-19 infections: 725 new cases, a record daily tally for any Australian state since the pandemic began.

Four weeks after Melbourne reintroduced stage 3 restrictions, logic suggests the coronavirus curve should have flattened and begun heading downwards by now. And on July 27, Victoria’s chief health officer Brett Sutton suggested the plateauing figures could represent the peak of the state’s daily case numbers.

But on August 2, Andrews announced Melbourne was moving to even stricter stage 4 restrictions, imposing a night-time curfew and shutting down a swathe of Victorian businesses for a further six weeks.

Read more: Which mask works best? We filmed people coughing and sneezing to find out

Why haven’t masks made a difference?

The premier announced on Tuesday a new deterrent aimed at those who continue to disregard the restrictions: a fine of $4,957, the largest on-the-spot fine applicable in Victoria. People who repeatedly breach the rules can also be taken to court, where the maximum penalty is $20,000.

Proper, widespread use of masks by the public should have made a big dent in coronavirus numbers. So why hasn’t there been a drop in cases?

It can’t be blamed entirely on the government’s response. A portion of the blame also lies with the public.

Philip Russo, president of the Australasian College of Infection Prevention and Control, last week lamented the “really obvious disoedience” displayed by some people, and speculated masks may also have created a false sense of security among the wider public who may view masks as more effective than they truly are.

Andrews said “far too many people” were going to work while sick, labelling this behaviour “the biggest driver of transmission” in the state. The stage 4 restrictions will clamp down heavily on this.

Julie Leask, a social scientist at the University of Sydney, said workers’ reluctance to call in sick was linked to how financially stable they feel, explaining that for casual workers, “isolation after a test could mean no work, less chance you will get a shift in future, and considerable financial stress. In that situation, it’s easy to rationalise a scratchy throat as just being a bit of a cold.”

Another difficulty is the lag time between when someone is infected and when they start showing symptoms.

What we are seeing now is actually infections from 5-10 days ago. And any public health interventions implemented now will take 5-10 days to show an effect.

Taking this time lag into account, the full effect of mandatory mask wearing will start to be seen this week.

We also know COVID-19 thrives in environments where it can quickly infect large numbers of people – and the recent uptick in cases has largely been driven by workplace transmission which occurred before the stage 4 restrictions came into effect.

Read more: ‘Far too many’ Victorians are going to work while sick. Far too many have no choice

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has announced a $1,500 disaster payment available to workers in Victoria who do not have sick leave and who need to self-isolate for 14 days.

Lax lockdown?

During July’s stage 3 lockdown, Melburnians were under the same restrictions as the original lockdown in March and April. Yet vehicle traffic was almost 20% higher than during the earlier lockdown (albeit well below normal, pre-pandemic levels).

Victorian government epidemiologist James McCaw said people generally haven’t changed their behaviour as much during the second lockdown as they did the first time around.

Nevertheless, there are early signs the stage 4 lockdown is markedly reducing the number of Melburnians who are out and about. On Monday, the first day of the new strictures, pedestrian numbers in the CBD plummeted. Typically, 1,300 people walk across Sandridge bridge during morning peak hour; on Monday it was just six.

Read more: Mapping COVID-19 spread in Melbourne shows link to job types and ability to stay home

The persistently high numbers may also be partly explained by infected people transmitting the virus to their families, partners or housemates – something that’s hard to avoid even in lockdown.

The government will presumably not attempt enforce mask wearing or social distancing within our own homes, yet this has profound implications for disease transmission.

It is helpful to consider your household as a single unit; if one person puts themself at risk, perhaps by not wearing a mask, they put their entire household at risk.

Masks have slowed “sharp upward trend”

While it’s frustrating that Victoria’s numbers have not trended downwards, it’s also true the state has successfully avoided the kind of exponential increase in cases seen in many other countries. An analysis published this week in the Medical Journal of Australia estimates that Victoria’s restrictions have averted between 9,000 and 37,000 coronavirus infections.

Masks are a crucial part of this, and the state government is distributing more than 1.37 million free reusable masks to those most in need.

Read more: A $200 fine for not wearing a mask is fair, as long as free masks go to those in need

It’s also possible Victoria is partly a victim of bad luck and unfortunate timing. The case clusters that spurred the second wave arose just as social distancing rules were easing after months of restrictions.

Regardless of how Victorians got here, it is clear what they must do next. It’s vital for people in Melbourne and Mitchell Shire to diligently follow the stage 4 restrictions, and that all Victorians maintain physical distancing, stay at home if unwell, get tested if they have symptoms, and self-isolate if they test positive.

Erin Smith is an associate professor in disaster and emergency response in the School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University.

This piece was first published at The Conversation.