What parties outside the ADHA might be important players in this potentially game-changing access project, and why?

The national Health Information Exchange project is, as outlined so far by the Australian Digital Health Agency, the centrepiece of the future digital health infrastructure (and true interoperability potential) of the Australian healthcare system.

As a result, it has the front-and-centre attention of a lot of major software platform vendors, software and system integrators, downstream suppliers to each, and even some savvy provider organisations that have cottoned on to how critical the project might end up being to the future operational effectiveness of the providers they represent.

The project is so big in its aspiration that it has started to take on a life of its own outside of the thus far limited framework for moving forward that the Agency has provided.

Speculation around what it will end up being, who will be involved and why, is rife.

So, let’s have a rough go at breaking down that speculation with what we know so far to see what might happen over the next year or so.

- This article was first published by Health Services Daily. Read the original here, or sign up for your discounted GP subscription here.

To begin with, it may be worth noting that is that this is probably not My Health Record 2.0 – and it had better not be.

The history of what went wrong with the MHR and why is there for everyone to see and to learn from. And while the current Agency leadership was not around to learn from some of the errors and so has limited corporate memory, there are plenty of good people working with the Agency or tangential to this effort for them to avoid making similar mistakes.

One irony of all those mistakes is that when originally conceived as the personally controlled electronic health record (PCEHR) well over a decade ago, the MHR was never meant to be a centralised repository of data. It was originally conceived as a series of federated data repositories that would be polled for data, which is what, in essence, an HIE should end up being.

Now, the MHR will likely be one of those many federated distributed data repositories that the HIE polls when someone needs specific information across the system.

It may even be an important one, as the ADHA plans for it to keep holding a lot of longitudinal information, some of which will always be very hard to get in real time from other parts of the system.

Perhaps still with the weight of politics behind it the ADHA has cast the MHR as an important synergistic partner to the precise and real-time capabilities of an HIE.

The MHR also has provided an important legislative framework for consent which will now form much of the privacy legislative framework for an HIE to operate nationally as well.

In all those important lessons learnt, and its possible role as some sort of synergistic counterweight to the new distributed HIE model, and in its consent framework, it may be that not all the more than $2 billion spent on the MHR has been wasted.

But for the MHR to survive into the new HIE era its fundamental architecture needs to be rebuilt to be properly FHIR-enabled for faster and more seamless sharing of its data, according to the Agency.

In this project, which the agency has listed as one of four major impending tenders scheduled for this year, we probably have the first iteration of the HIE project. So who tenders and who wins might be informative as to what happens down the line when the most critical component of the HIE goes to tender.

The most important component down the line will be for a system that can search for, find and access in real time, meaningful data anywhere in the system that someone somewhere else in the system needs urgently.

The nature of the search component of an HIE the ADHA has in mind at this stage is the subject of a lot of speculation and will likely depend on a few variables that have yet to be settled.

Are they going to go for something that can poll to an intimate distributed level for instance? Say, an individual EMR in a hospital or a patient management system in a single GP practice?

Or, will they be looking for something that operates a little more upstream? Like, for instance, something that can poll the NSW single digital front door and let that state’s HIE do all the heavy lifting of hospital-by-hospital and pathology group by pathology group data?

Maybe, if the big GP patient management systems can manage it one day — they will need a lot of work from here to do this – poll one of the major PMSs and let that system do all the downstream work of getting individual GP practice data that might be needed.

More detail of what sort of distributed architecture searching the agency has in mind will mean vendors and integrators can get a much better handle on what existing technologies and platforms might be in play, and just how much integration work will be required to get such a system up and maintain it.

To give you a quick sense of what is up for grabs financially, currently the MHR has a maintenance bill of upwards of a $120 million per year – software licensing, cloud hosting, maintenance and ongoing integration work – and that’s for a single centralised data repository which is accepting and storing information mostly, and not yet doing much meaningful distribution of that data to the many points of the healthcare system compass that do poll it.

The exorbitant cost of maintaining an MHR which isn’t that accessible (and not usually in real time) is one reason the Agency is going out first to upgrade their favourite database.

They want to be able to release any latent potential that is trapped in the MHR given how much data they already managed to get into it.

A key problem now is that it’s hard data to get at, but if the Agency can make it much easier they might be able to make the MHR a lot more useful going forward and in particular, they might actually be able to make it a coordinated part of information sharing with the HIE they eventually build.

Which should mean that the first important tender for the HIE is already largely in play.

Whoever wins the tender to upgrade the MHR to proper FHIR-enabled capability should be in a good position to keep working with the Agency in developing the broader HIE ecosystem, especially if they do a good job early.

So, who might be potential candidate third parties for participation in the project via this early-stage work?

The MHR tender is in two parts:

- Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) Server products and/or services listed as application implementation services;

- Operational management and product enhancement services listed as system administrators.

You probably can’t rule out the incumbent system integrator and maintainer, Accenture, and the various deeply imbedded platform vendors in the current operational paradigm of the project, which includes Oracle and Microsoft.

Accenture presents something of a dilemma though.

On the one hand they are the long-term builders of something which is not fit for purpose for which they have been paid hundreds of millions of dollars over the years.

On the other hand, they are a large and capable integrator with access to plenty of FHIR expertise and lots of overseas experience building similar platforms.

Whose fault was it that the original design concept was so flawed anyway?

Also, Accenture will clearly understand where the skeletons are buried in the existing set up which should give them a leg up in trying to bridge to the new FHIR-enabled iteration.

But you’d have to think that after hundreds of millions spent for so little return in 10 years as an incumbent operator the political optics of sticking with Accenture would be difficult. Especially when there are plenty of other capable integrators out there.

Obviously, Accenture are interested and working on their positioning. Rumour has it that they are also very interested in being the integration partner for the discovery component of the HIE, which looks like it will be the main game moving forward.

Accenture might end up trying to partner with Microsoft in this respect.

The core HIE work will be the discovery and presentation component, for which the requirements at this point of time remain too unclear for most platform vendors to get a sense of whether they have a shot at meaningful participation.

This is despite the recent review of progress by the Connected Care Council listing the following as one of nine completed tasks in the long list from the Agency’s interoperability plan:

“Drafting a National Health Information Exchange architecture and roadmap in consultation with jurisdictions and key stakeholders…”

Most vendors waiting on the sidelines are going to tell you that there is nothing like a draft architecture of the HIE available yet. Certainly nothing that they can take and start planning around.

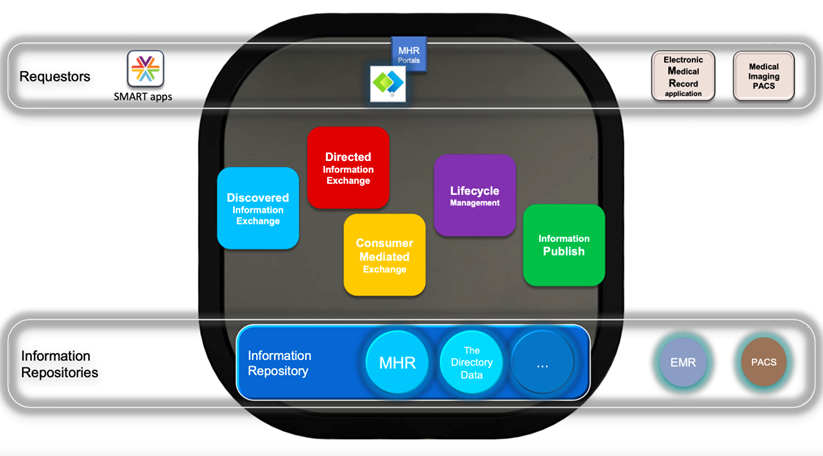

There is a very high-level architectural view from the Agency and a series of concepts, one of which is the idea of “interoperability patterns”.

The Agency presented this slide around that concept at its recent information day, but talking to various vendors, it doesn’t make things any clearer in terms of actual architectural requirements. Each of the boxes in the middle represent an interoperability pattern.

Whatever detailed architectural requirements eventually emerge, the project is likely going to need a core platform product of some description and someone to build and integrate it with the other existing components of the plan.

Normally an owner would seek a consortium which would bring both an integration partner and a vendor or two. An intriguing possibility suggested by one analyst recently is that the Agency might end up going out separately for each element, the logic being that when you accept them as a team, like we have with Accenture and Oracle, you have no leverage and less flexibility moving forward.

There are quite a few vendors with products that might be in play who already have a track record in Australia and overseas, including Oracle, Intersystems, Orion, Altera, and possibly even iterations of the current Microsoft CRM medical stack and Salesforce’s Mulesoft.

There is also SMILE, which is a highly rated HIE platform, working already and with plenty of plaudits for how it is working in parts of Canada and the US, and which was recently introduced to Australia through an exclusive licensing deal with Telstra Health.

Telstra Health has worked with SMILE to incorporate it into its virtual care platform, but if SMILE were to end up the platform of choice, it’s likely that it would need to work with a major integrator outside of Telstra Health, as Telstra does not have that capability in house. That might make for some interesting licensing negotiations.

Outside of the above, there are also some major global vendors who so far haven’t operated in Australia much yet or at all such as AxSyx Technology and Medcity.

It’s likely that one of the major global integrators will try to partner up with one of these groups.

It starting to look pretty busy behind the scenes.

On the integrator side of things there is also a long line-up of interested parties.

When the time is right most of the usual suspects – Deloitte, Accenture, KPMG, Scyne Advisory – are likely to cosy up with one or more of the above vendors in a consortium to bid.

But the usual suspects are very likely to have quite a bit of competition from a few US-based system integrator groups that have already been there and done that via the 21st Century Cures Act in the US, and through existing major contracts with major HIE-type service providers in the US such as Commonwell.

One such group that is expressing quite a bit of interest in Australia, given the new strategic direction of creating a distributed search paradigm, is Ellkay.

When you look at Ellkay you see an enormous amount of experience and expertise in building and running HIE-type technology in every aspect of a healthcare system, including interoperability between hospitals, laboratories and various ambulatory systems and a lot of FHIR integration capability

Ellkay is also the major integrator for what is one the two largest HIE providers in the US system, Commonwell.

Commonwell has been involved in the US journey from the start so it understands what to do and not to do if you are rolling out an HIE system along the lines of the US. Notably the Agency is following quite a bit of the script from the US rollout of a distributed system based on clusters of HIEs.

There are other companies in the US like Ellkay which might be interested as well, like Redux Engine.

Related

Another interesting potential player in terms of system integration which is US based is Leidos. It is a major US consultant and integrator that most people wouldn’t associate much with Australia let alone healthcare. But they’d be wrong.

Leidos is the lead on a massive transformation contract of the entire Australian defence healthcare system called JP2060 and a lot of that contract has been done well.

Leidos has also led major interoperability projects in healthcare for the US government.

The system that Leidos is overseeing and delivering for defence in Australia has probably the most advanced interoperability capabilities of any health system in Australia, connecting hospitals to GPs to pharmacists to dentists and allied professionals via both FHIR-enabled cloud technologies and with redundancy built in for on premise operational capability when needed – which you obviously do at times in the military.

The system will eventually even talk to a submarine parked somewhere at the bottom of the ocean, to give you some idea of the problems Leidos is having to solve.

As an enclosed system (defence personnel only), it provides several examples of the sort of interoperability that the broader healthcare system is aching for, such as a clean line of data sharing between hospitals, GPs and community services.

Of course, JP2060 doesn’t have to worry about the vast complexities of Medicare and activity-based state hospital funding models and all the payment problems that go with that, so implementing such neat solutions has been made easier.

But as an example of what you can achieve, Leidos certainly has some interesting IP to bring to the table now, including IP from other interesting local cloud and AI-based software platform vendors such as MediRecords and Alcidion.

In all this mix you are also likely to see some of the specialised consultants such as Nous involved in some parts of the process, at least in a strategic and planning sense.

If the project is going to work in the manner that the Agency is envisioning there is also going to need to be significant involvement along the way from our major local GP and allied health patient management system vendors.

It’s not likely that any will be part of a consortium for the core part of the HIE project but it’s certain that if the major GP and allied patient management systems don’t adapt quickly to be able to talk to the new HIE via some sort of FHIR-enabled functionality, then the most important patient information will be lost to the project and the project will fail.

It feels a little like the Agency might have approached their HIE plans more from the hospital side of things than the GP side of things, which could ultimately present a very big problem to the project.

The GP systems, though not strictly in the HIE project, are absolutely critical to the success of the project. If in the end they can’t talk in real time to the HIE and through it providers and patients, then nothing will work.

GPs and the information they have and transact on are the hub of any system that is aiming to shift its focus onto chronic care management into the future.

Both major GP systems in Australia have plans to move in alignment with the HIE project and both are deeply imbedded in important projects like Sparked.

But their intent to move forward and involvement at the heart of interoperability activity may not be enough. Moving their platforms from old on-premise server-bound systems to cloud-enabled sharing systems is ultimately a massive business challenge for the major vendors.

And it’s not just going to be expensive for the vendors to do the work.

GPs don’t have any money to invest in new systems and we know that moving from their familiar on-premise UIs and processes to cloud is anathema to them.

It’s a big change that ultimately the government is going to need to help the GP community with a lot more than is currently planned.

And when and if the vendors do succeed in doing what the Agency and DoHAC want – rearchitecting their systems to be able to share meaningful patient data in real time with other providers and their patients, likely through their HIE – a good chunk of their current business models, which involve taking a cut from various integrators to exist to their on-premise systems, will likely disappear.

And that chain of events means there are lot of applications that currently integrate with the on-premise PMSs that will face business model problems with cloud themselves.

For example, if a patient management system does have a fully functional FHIR cloud interface it’s likely that they’ll be able to talk directly to all their GPs patients, and that might mean they won’t need the booking engines anywhere near as much as they did in the past.

With something like 70% share of GPs and therefore GP patients, Best Practice will be in a powerful position to simply move away from some third-party applications and take the money they make, directly.

It’s hard to think of any point of the software vendor compass that isn’t in some way materially affected by the plans the Agency and the government have for the HIE.

For some it’s lining up to be a party.

For others maybe not so much.