The life-or-death clinical standoff and what you can do to turn it around.

It doesn’t happen a lot, but when it does it can be infuriating and distressing: the patient who refuses treatment.

While some doctors take a “my way or the highway” approach, others have found a better path to working with patients who say no to conventional therapies.

When you think of people who refuse cancer treatment, Steve Jobs – the co-founder of Apple – immediately springs to mind.

He was the unfortunate poster child for treatment refusal when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2003. Jobs tried alternative therapies such as acupuncture and special diets that are touted widely as cures for cancer online. When he later changed his mind and accepted conventional treatment, it was too late to have made a difference and he died in 2011.

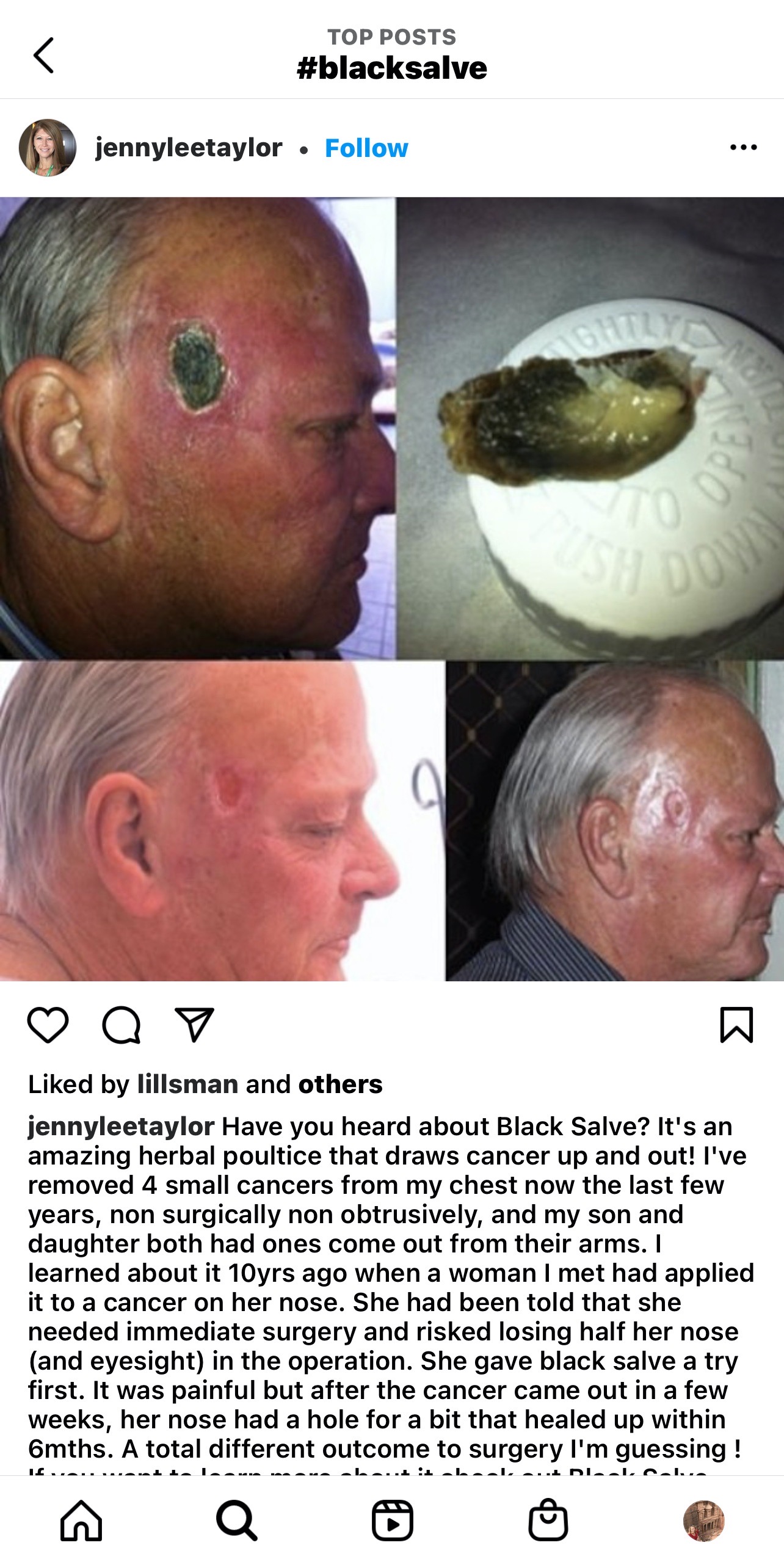

Online communities that support alternative treatment often label conventional therapy as toxic and alternative medicines as “natural” and safe, and fail to provide information about how deadly some cancers are leftuntreated. Some social media groups also peddle alternative remedies that are quite questionable and disturbing.

“It’s false information that alternative treatments are safer,” said Professor Christobel Saunders, professor of surgical oncology at the University of Western Australia.

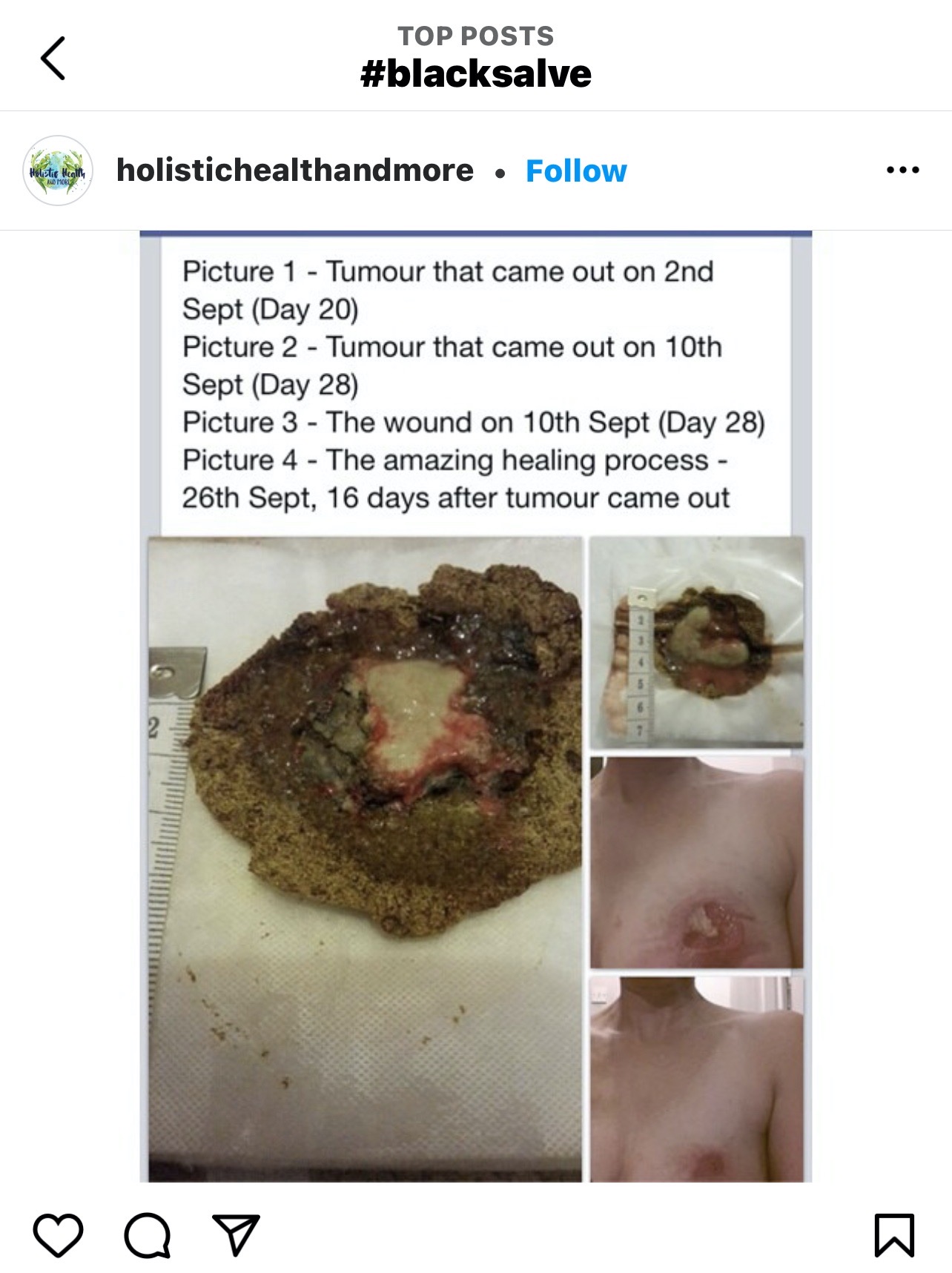

“Some patients try quite nasty treatments on themselves. I mean, it isn’t pleasant going on starvation diets or giving yourself a coffee enema or applying black salve that burns great holes in you.”

Black salve is a formulation that usually includes bloodroot and zinc chloride, and slowly burns off flesh when it’s applied. People have tried to remove breast and ovarian cancers by topical application.

Other troubling alternative treatments for cancer include oral dosing of laetrile, which breaks down into cyanide, and expensive herbal and supplement regimes. None of these have robust scientific evidence to support their use and there’s increasing exposure to this kind of misinformation on social media.

“People can now very easily justify their model of disease online and find others who support that model,” said Professor Saunders.

“When you go into a search engine and start researching those topics, the next time you go online, alternative treatments ads pop up and take you further and further down that rabbit hole.”

Is there a “type”?

There is not a vast amount of research on people who refuse conventional treatment for cancer, according to Professor Saunders. This group of patients is more sceptical about medicine and are therefore less likely to want to participate in a scientific trial, she said.

“But it’s not one size fits all,” said Professor Saunders. “This is not one group of people. There are different motivations and nuances.

“For some, it’s a very specific reason such as a religious or a psychiatric condition. But the larger group is actually well educated, younger, healthier, fitter, and they have a high need for decision-making control.”

An Australian study from 2012 suggested that one in four cancer survivors has used alternative treatments and dietary supplements but no Australian research is tracking numbers to see if refusal of conventional treatment rising.

Danielle Spence, the head of cancer strategy and support at Cancer Council Victoria, agrees that the reasons for refusal are quite broad. She urges health professionals to take the time to understand what those issues are.

“It can be misconceptions and myths or cultural misinformation,” Ms Spence said. “It can be stigma. Some people don’t have a relationship with a GP. They might be too embarrassed to come forward. Some people might not be able to stop working or caring for children.”

A lack of health literacy combined with fake news on social media makes it difficult to reach those who are hesitant about conventional treatment.

“When we take those calls on our Cancer Council information line we’ve really got to try and unpack what’s influencing the caller,” Mrs Spence said. “And it can be coercion from people online.”

Ms Spence also said that some people are really fearful of cost. Research shows that half of the Australians who are diagnosed with cancer will have out-of-pocket costs exceeding $5,000 within five years.

“It’s a significant cost for many Australians,” Ms Spence said.

What’s a doctor to do?

What many psychologists and doctors have found is the best starting point is to just be really curious about the reasons a patient is avoiding cancer treatment. But that is often not what happens.

Associate Professor Lesley Stafford, a clinical psychologist at the Royal Women’s Hospital Melbourne, has had doctors refer breast cancer patients to her for psychological services.

These women have been labeled “difficult” by doctors who assume that there is something psychologically wrong with the patient because they question conventional treatment.

Professor Stafford said that it’s indicative of a breakdown of the doctor/patient relationship, which reinforces the patient’s treatment hesitancy.

In one small American study, researchers followed 60 women with breast cancer, half of whom refused conventional treatment and half of whom accepted both conventional treatment and alternative treatment.

The women who declined conventional treatment perceived their oncologist as being uncaring, insensitive and unnecessarily harsh. They felt the doctor didn’t understand the depth of their fear.

“They also weren’t necessarily opposed to conventional therapy, but they were worried about the side effects,” Professor Stafford said. “They needed time to think and educate themselves. And they wanted to be cared for by a doctor who could offer hope and encouragement during treatment.”

The study showed that the patients were also more likely to believe that alternative treatment was safer. They may have also witnessed suffering or loss of family members from cancer.

“These types of patients tend to have a greater belief in their ability to exercise influence over their life events,” Professor Stafford said. “There’s a kind of a strong belief system in this group in favour of a whole person healing.”

But when the patient feels sidelined, and the doctor is tearing their hair out, the onus has to be on the health professional to be the bigger person, said Professor Stafford. They must find a non-judgmental starting point for a conversation and explore the fears and what’s driving the hesitancy.

A part of this frustrating and sometimes distressing divide is that doctors and patients are thinking about treatment from two very different perspectives. Health professionals are generally goal oriented and value scientific evidence. But many patients base their decisions more on their personal values and experience.

From the point of view of the doctor, when a patient rejects medical advice it can feel as though they’re challenging a doctor’s expert status and their reputation.

“When a patient refuses life-saving treatment, it goes against everything a doctor works for,” said Professor Stafford.

“And that’s where the conflict comes in, because it just beggars belief, the doctors cannot understand it. Then the doctor gets riled up, the patient starts to feel alienated and the relationship breaks down.”

Professor Stafford suggests that doctors stop and think: “What am I feeling? Am I getting irritated? Am I too angry to listen? Am I actually feeling punitive now?”

“Don’t go too heavy too soon before exploring what the barriers are,” she said. “And tell the patient what’s worrying you without blaming them. Try to validate how patients feel and be explicit.”

Professor Stafford suggested the following conversation approaches:

- ‘Let’s think about how we can work together to do the best we can to manage your disease.’

- ‘I can see these decisions need a bit of thought and I can see you need some time to process that information. It is a lot of information to assimilate.’

- ‘I know the quality of your life is important to you. I don’t want you to feel coerced or rushed.’

- ‘It sounds like it’s really important that you have control over what happens to your body.’

- ‘I hear that you are really afraid of the side effects.’

- ‘I can hear that you witnessed a lot of suffering when your dad had his chemotherapy.’

- ‘I wish I could say that omitting chemotherapy would be safe for you. But I can’t.’

- ‘Let’s think about the big picture: what we’re hoping for in the treatment of your cancer.’

- ‘Can I suggest we trial some options?’

- ‘I’m really worried because I know that a raw food diet alone is not going to help prevent a recurrence.’

- ‘I want to show you this paper that describes what happens to women who use only alternative therapy to the exclusion of conventional therapy.’

Another suggestion offered by Professor Stafford was to focus more on the positive options and outcomes.

“Doctors also often spend quite a bit of time talking about the toxicities of chemotherapy, but they don’t spend enough time explaining what we do to counteract those toxicities,” she said.

“We forget to tell patients that they actually get a truckload of steroids upfront that helps with nausea and vomiting. And breast cancer women now use these fantastic cooling caps to reduce hair loss. So, there’s lots of things that we can do to counteract that horrible toxicity and to take away some of the fear.”

A phrase I have repeatedly heard in interviews with psychologists and doctors was “you have to leave the door open”. Leave the door open for the patient to feel OK to come back for more information without feeling shame and that the patient won’t be worried the doctor will be smug or patronising about their change of mind.

“It’s not ‘my way or the highway’,” said Professor Saunders. “First, explore the reasons why a person is thinking that way and try to meet them halfway. You have to keep open the ability for them to come back.

“You also need to be careful that you don’t collude with the patient,” she said. “But I think we can offer patients a lot more complementary treatments now as an accepted part of mainstream cancer.”

Professor Saunders said offering options such as meditation, yoga and acupuncture could help patients cope better with cancer but also have an added bonus for doctors.

“The patient will see you as a more holistic practitioner rather than just somebody who wants to give them chemotherapy,” she said.

The bigger picture

Ms Danielle Spence’s experience at Cancer Council Victoria suggests there’s much to be done beyond the treatment room, she said.

“We have to do more as an oncology sector to address misinformation,” she said. “We need to rule out the unscrupulous, non-evidence-based providers and get them out of the system so people don’t get coerced.”

Unlike the UK, Australia does not have a Cancer Act that prevents patients from predatory advertising of alternative treatments. But the cancer sector’s response to covid-19 could provide one solution, she said.

“Around 85% of Australian people with cancer have had at least one dose of a covid vaccine,” said Ms Spence.

“But that’s been a concerted effort with all of the sector coming together to develop those key vaccination messages in public-facing ways. And that could be a good precedent on how we tackle misinformation around alternative cancer treatments.”

That messaging needs to be consistent, whether it be in clinics or in communication with the Cancer Council, she said.

“It’s also about surrounding that person who is hesitant with resources and ways to access information,” added Ms Spence.

“It’s coming at it from all angles and making it contemporary; like giving patients platforms they can access on smartphones. There are also great ways that you can support patients with programs such as Cancer Connect, where they meet someone else who’s had a shared experience.”

What covid has made clear, though, is the increasing influence of social media over medical decision making.

Refusing conventional treatment can be distressing for both patients and doctors – and profoundly tragic when the outcome is fatal for the patient.

“When you talk to clinicians, most of them will say it’s a small minority of people,” Ms Spence said. “But for health professionals, it’s a devastating clinical situation. It is those cases that everybody remembers.”