How to handle it and stop it happening again. And again.

After a challenging few weeks, a friend and colleague reached out to say “Are you OK? You’ve been quiet of late, hope all is well.”

So we had a chat. No, I was not OK. Yes, I was stressed. Yes, I was exhausted and had had some challenging conversations with patients that had resulted in my ending the therapeutic relationship.

She listened, then said, “It must be the way things have changed since covid. We’ve had a rise in that too, patients threatening to complain if they can’t get in to see us the day they call.”

One of my receptionists was far more pragmatic when I was sitting on my pitypot after a particularly fruitless phone call in which I terminated the relationship after one too many issues. I said to her, “What am I doing wrong?” She said, “Maybe it’s not that you’re doing anything wrong; maybe it is that we are seeing more people and some of those people, statistically, are bound to be people who aren’t a good fit for the way we work.”

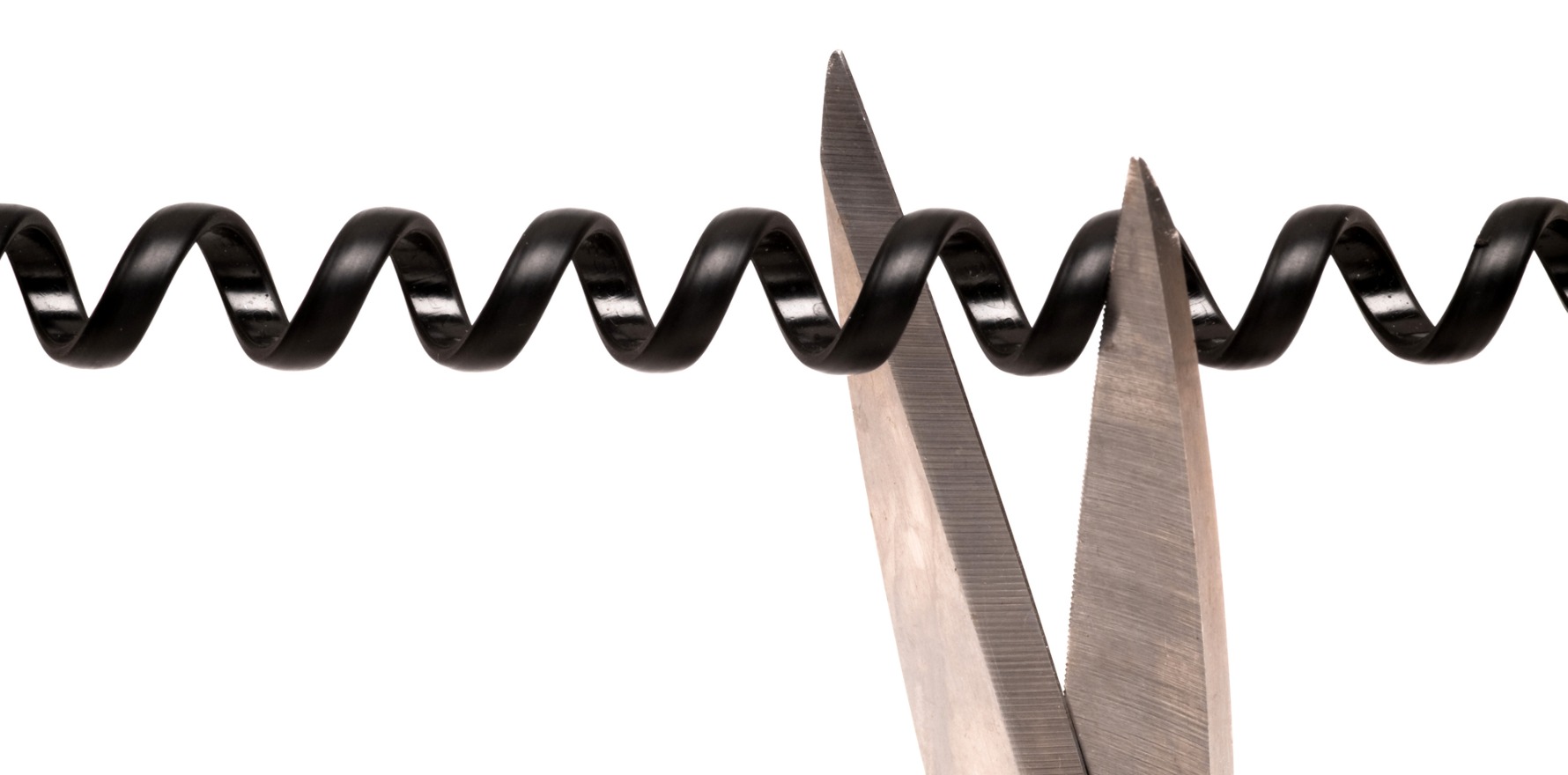

It’s been a time to revisit our MDO guidelines on how to end the doctor-patient relationship, as some people seem to be under the impression that this is a one-way street. “You can’t fire me, I pay your bills!”

This is what I’ve been told:

- It’s not necessary to end the relationship in person, though it’s ideal

- It IS necessary to advise them of the end of the relationship and their options going forward, including providing alternatives e.g. scripts and adequate cover till they can find someone else, especially for time-sensitive care

- It is important to place this information in writing, for their safety and yours, as we absorb less when we are upset and stressed

- It is OK to end a relationship for issues such as failure to comply, repeated cancellations and rechedulings, failure to pay fees and to follow other policies

- Some incidents are grounds for immediate bans such as (verbal) abuse or sexual overtures

It is also important to recognise that when a patient tells you “I’ll take my business elsewhere if you won’t do XYZ”, it is OK to let them do so.

On the two occasions I’ve done this, both have backed down and asked to stay with me.

Maybe it is covid.

Maybe it’s the pervasive posting on social media platforms about having to “advocate for” themselves, their friend or loved one against “gaslighting” by doctors and “medical misogyny”.

Related

I’d be the first to say there are many of us in health who likely should not be, many who aren’t very good at caring for people and many who communicate poorly. It’s likely some of us do have outdated access to guidelines and are less sympathetic to women’s pain.

That does not mean that all of us are bad, incompetent or, as is regularly implied, out to harm our patients.

We likely no longer carry the authority as a group that we once did, but we are still held to very, very high standards by the regulators and the general public.

In many groups, I’ve seen people use the threat of complaints as a first-line remedy instead of talking to their doctor.

Especially since covid, the line between work and personal life can blur to the extent that we are often expected to be on at all times for our patients, who email with photos for medical advice between consults and direct message on social media (“I’ve also emailed but just letting you know here too”).

And the pushback when we say no is sometimes threats. Threats of leaving and “taking my business elsewhere”, of complaints, and occasionally of lawyers.

It’s exhausting.

As a result, I’m finding, as a largely procedural GP, that the bulk of my initial consultations now are spent in assessing the new patient for red flags once I know they have an issue that I can help with. Are they likely to have unrealistic expectations? What are they expecting? Will they complain? Will they ask for a refund if something goes amiss? Will they say “if I’d known this might happen I’d never have had the treatment”?

Having spent a decade in a high-pressure surgical speciality (O&G) where we had to push back regularly against birth plans that risked the health of mothers and babies, this feels like more of the same.

All that work, all that consent, all those discussions, all those cooling-off periods, only to be told “If I’d known…” or be accused of not caring enough.

My patients who work in dentistry, orthodontics, surgery, psychotherapy, tell me this is what they are seeing too.

My MO going forward is making the covert overt at the first line crossed. Even after 11+ years of mental health training including psychotherapy, this is hard.

“Ms X, you’re 20 minutes late to a 30-minute appointment, so we have 10 minutes left as my next patient is already here and I don’t want to keep them waiting.”

“Mr Y, I know you said that as a backhanded compliment, but it’s not OK and I find it offensive.”

“Look, Z, if you reschedule/late cancel one more time, I’ll have to end our working relationship. Would it be easier for you to schedule an appointment when you can guarantee you’ll attend?”

And then I write these down in the consultation in the event of any complaints or disputes later. As the MDO advised me, “If it is something that was said, you’re allowed to write down the facts as you recall them even if they request a copy of their notes later.”

Effective boundaries and communication is something none of us is taught, and the lack of them is, I’m convinced, one of the biggest contributors to burnout among doctors. Many of us are leaving due to the persistent injury of being told we are not good enough because we refuse to be doormats, or called “bitches” and worse if we dare to have boundaries that we hold others to.

It’s fine to have expectations, the MDO told me. Make them explicit. “Here’s what you can expect from me as your doctor. In return, here’s what I expect from you as my patient.”

She even told me to put it on my website for prospective patients to peruse, and to raise it at the first consultation. That way, when there is a problem, you can say “remember that conversation we had around … ?”

Without these boundaries, the thought of retiring from medicine and working in a supermarket as a checkout chick can seem sweet. I know it has been for me of late, and that is a signal that I’m slipping and need to tighten my boundaries.

Dr Imaan Joshi is a Sydney GP; she tweets @imaanjoshi.