Behind every new system, there is a temptation to mine data, and then the even more attractive prospect of monetising the data-mining activity.

Recently the government announced the removal of the 2712 and 2713, two item numbers for mental health consultations in general practice.

I’ve been asked what I think about this, and I’m conflicted.

In one sense, I think this is a good thing.

It has always been financially unfair to have a cap on the length of a mental health consultation. Why should a 40-minute physical health consultation bring in a rebate of $122 and a 40-minute mental health consultation just $82?

The impact has been to widen the gender pay gap, because the majority of patients with mental health needs see female GPs.

Removing the 2713 also removes the complexity of deciding when a GP can co-bill a 2713 and 23, which has been the cause of much angst for GPs and the bureaucrats who police the MBS.

It is impossible to tease out mental health from physical health in a typical consultation. Which bits are which? Do I allocate family history to the mental or the physical part of the equation, or is it equally allocated? What about sexual health, tension headache or carer stress?

Because we fear the PSR, we have historically underbilled to avoid this risk.

The change reduces the problem of announcing a person’s condition to the MBS using an item number. Consumers tell us that there are still implications for their insurance when mental health needs are flagged, and this is discriminatory.

However, I know that there will be a problem with data once these numbers are gone. I have never seen a situation where governments are happy with less data than they had in the past.

At the moment, mental health activity in general practice is counted using mental health item numbers, a surrogate measure of mental healthcare activity in general practice. This metric is, of course, an underestimate of our mental health work, because we all do more mental health work than is captured by our billing, but it is something.

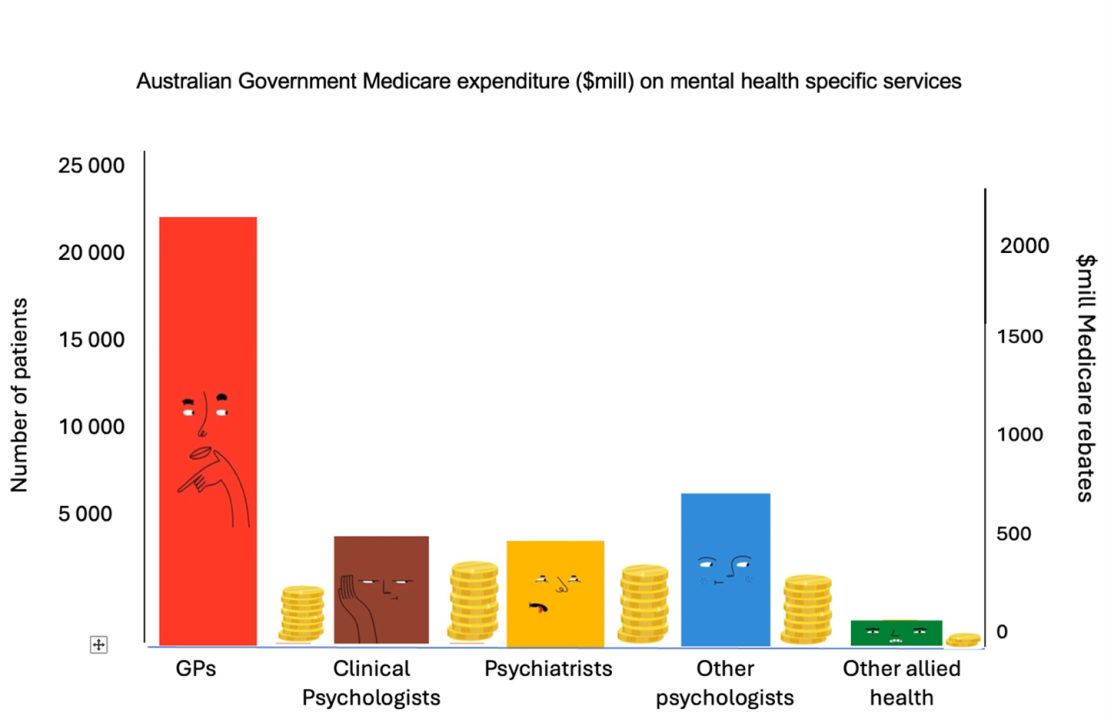

Existing data gives us an opportunity to represent the importance of GPs in mental health care.

I am always bewildered by the exclusion of GPs in mental health policy and planning committees (including in my state of the ACT) and the gross underestimation of what we actually do. I am beyond frustrated at the tendency to see my role as referring into services and being educated by them.

I am not a passive learner and have my own knowledge and skills to contribute. Psychologists and psychiatrists are not the experts in the patients they will never see.

I need figures to demonstrate the argument. Here is the graph showing the number of patients seen by each profession. GP numbers are calculated using the mental health item numbers billed, seen on the left. The cost to the taxpayer is seen on the right. It’s an excellent demonstration of our efficient management of a broad scope of patients.

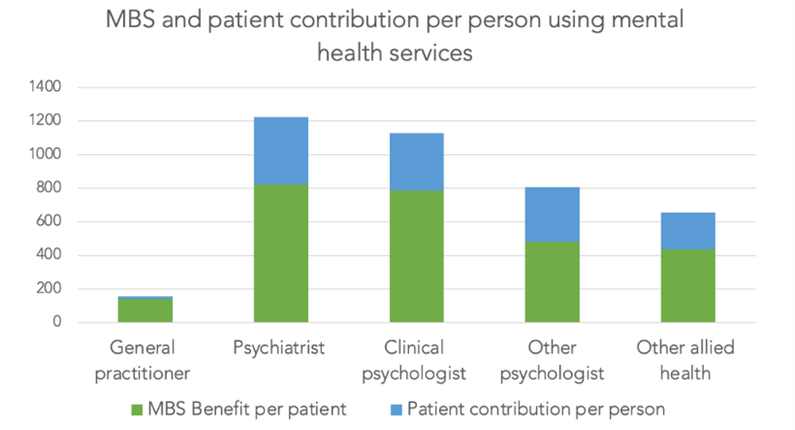

In response to the argument that we are expensive, and exploit poor, vulnerable patients, I have this graph.

Both graphs are based on the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing.

We charge, on average, $16 out of pocket per patient per year in mental health, hardly enough to bankrupt the average patient.

Without this data, I worry the void will be filled one of two ways.

The policymakers may represent our work counting mental health treatment plans, a gross underestimate of our mental health activity. Or they may count the number of times a patient thinks they discuss their mental health with their GP, again likely to be a gross underestimate of what we do.

Related

An alternative, of course, is even more scary.

The data entrepreneurs have a product that will provide a solution, with an associated business model. They are likely to reference the data they have in their handy AI databases.

Why use academic research, they will say, because AI already collects appropriate data? Governments can crunch the numbers by extracting mental health references in the entire database of transcripts of real GP consultations with real patients.

There is no risk to individuals, the government and AI companies will say, because the data is de-identified. Behind the data GPs see, the companies must have entire transcripts, so they can just count the number of times a GP uses the following words …

To make this even scarier, it is unlikely to be subject to ethical approval.

During the nudge letter period, research was done on GPs without their knowledge or consent, to see which phrasing was most effective in modifying their practice. The team involved thought it was appropriate to avoid consenting the GPs, because the intervention was going to happen anyway, as it was auspiced by the federal government.

Where do ethics fit in mining clinical data when it is gathered to “reduce low value care”? Will the GPs know? Will the patients know? How will the data be interpreted when we extract only words and turn them into numbers, ignoring the complexity of the interaction between doctor and patient?

Behind every new system, there is a temptation to mine data, and then the even more attractive prospect of monetising the data-mining activity. Data mining, as we have seen recently, can also be used to ensure compliance. It’s a short step to implementing an intervention to “reduce low value care”, ensuring GPs adhere to guidelines in their management of mental health conditions.

The carrot to GPs will be that it “will free up our time to focus on the patient” using AI, and potentially a small incentive. The risk is an enormous step up in surveillance, of our work and our patients’ “private” health needs which, historically, is likely to make inequity worse.

In my experience, every technological innovation has promised to free up my time but has, instead, brought with it the potential for more audit, forms, regulation and time on administrative tasks. It has also reduced privacy.

So, I am conflicted on this front. Counting activity using item numbers in general practice is poor practice. However, the alternative for governments voracious to increase outcomes and reduce costs may well be worse.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.