No drug is a silver bullet for low back pain, but a new Australian review suggests there may be a few bronze-coated options available.

NSAIDs and opioids are best for low back pain, according to possibly the most comprehensive review into pharmacological treatments for the condition.

Surprisingly, researchers found ‘high certainty’ evidence tapentadol led to a small reduction in chronic low back pain.

While drugs are the most common treatment option for both acute and chronic low back pain, countless studies and reviews (of varying quality) into the efficacy of each make it difficult for clinicians, policymakers and the public to easily assess what works – and what doesn’t.

A new overview of seven Cochrane reviews (including over 100 studies and 22,000 participants), published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, cuts through the noise and collates the relevant efficacy, effectiveness and safety data into one useable document.

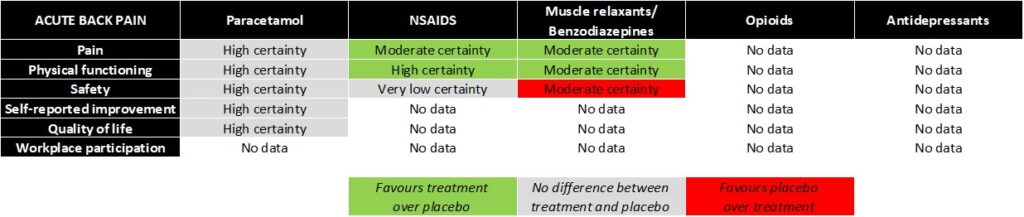

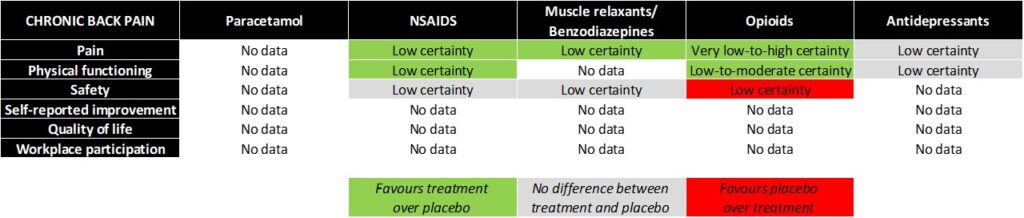

Researchers failed to find any moderate- or high-certainty evidence that any of the treatments they investigated – paracetamol, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants/benzodiazepines, opioids and antidepressants – provided a medium or large effect on pain intensity (defined as a reduction of 10 or more points on a 0-100 scale) for acute or chronic low back pain compared to placebo.

However, NSAIDs got the nod for acute low back pain ahead of muscle relaxants/benzodiazepines despite both treatments having moderate-certainty evidence of a small benefit on pain. This is because NSAIDs had very low-certainty evidence of no increased risk of adverse events, while there was moderate-certainty evidence of an increased risk of adverse events for muscle relaxants and benzodiazepines.

There was high certainty evidence paracetamol had no effect on pain (compared to placebo), nor were there any data for the use of opioids and antidepressants in acute low back pain.

Summary of evidence for pharmacological treatments in acute low back pain

Researchers also found low-certainty evidence that NSAIDs may provide a small benefit for chronic low back pain.

As for opioids, there was very low- to high-certainty evidence that opioids provided some benefit for chronic low back pain, depending on the specific opioid used.

For example, there was high-certainty evidence that tapentadol led to a small reduction in pain, low-certainty evidence that tramadol led to a medium reduction in chronic low back pain, and very low-certainty evidence that buprenorphine led to a small reduction in chronic low back pain. However, opioids should be used judiciously due to their well-established side effects, including nausea, headache and constipation, the authors said.

Summary of evidence for pharmacological treatments in chronic low back pain

“It’s starting to become quite clear Cochrane reviews are of [a] higher quality than reviews done in the wild. By focusing on Cochrane reviews for this high-level synthesis, we think you can be more certain, or trust the evidence we’ve generated more than if you were to include other reviews,” said Dr Aidan Cashin (PhD), lead author and postdoctoral research fellow at Neuroscience Research Australia.

“The broad finding is that drugs or medicines for low back pain don’t work as well as we thought they might, or may want them to,” Dr Cashin told TMR ahead of his presentation at last week’s Sydney Spinal Symposium.

“[But] medicines or drugs will always have a place in the management of low back pain. There’s a clear need to prioritise non-pharmacological treatments – good quality advice and education about their condition, structured exercise and psychological support – where appropriate and available.”

Dr Cashin emphasised the importance of remembering the review only compared each treatment against a placebo, not another drug.

“We recently conducted a network meta-analysis for people with acute low back pain, where we wanted to compare each medicine against each other to determine which one you should prescribe.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t have a rich or developed enough evidence base to provide certain or reliable evidence of what people should do. I feel that really talks with the evidence base for medicines in back pain – it’s incomplete and quite disconnected,” he told TMR.

Researchers noted a slight reduction in confidence in their findings, with all bar one Cochrane review being more than five years old, meaning the studies included in the reviews could be 15 to 20 years old. Dr Cashin and his colleagues are planning to update several of the reviews in the coming years.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, online 4 April