If GPs weren’t so insecure, we wouldn’t fear losing the low-hanging clinical fruit – we might be happy to leave it to others.

I recently received a rather sad email asking me, as medical practitioner, about a recent article that was published by a certain prominent college body about community pharmacists.

The article questioned whether community pharmacy was in fact needed, or whether perhaps it was better to have a centralised pharmacy unit where all the dispensing can happen, with medications sent direct to the consumer.

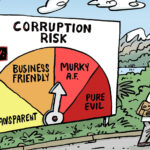

This was in response to the latest attempt by the community pharmacy sector to colonise work usually done by GPs, and represents another skirmish in the turf war between pharmacists and doctors.

This concept of turf war and power play has never really made much sense to me. I, and probably most clinicians, would say that we are all on the same team and that our sole purpose is to serve and help our patients.

Yes, we must look after our business needs and our own wellbeing, but then shouldn’t our focus be on efficacy and maximisation of our resources, rather than competing?

I wondered: what is driving this behaviour?

There must be some intellectual reasoning behind it, as the comments are usually made by highly reputable organisations and individuals.

In my opinion it comes down to three main elements.

1. Politics

Anecdotally, the Pharmacy Guild has been regarded as a strong political advocacy group for pharmacists, with nearly 75% of practice owners being part of the guild. They have the money. They have the members, and they have the executive structure to have meaningful and powerful conversations with the decision makers. There are no questions about this. They have a voice.

In comparison, in the medical world, we lack a similarly cohesive fraternity under one roof, one with a strong financial and executive functioning. There are various organisations representing many different crafts within the medical fraternity, but without that unity, we lack an effective voice.

2. Invalidation and insecurities

I can totally understand why GPs and other medicos would be distressed about the expansion of scope in the pharmacy world. Every day I hear my peers joking that now that pharmacists can prescribe meds and do vaccinations, what’s the point in being a doctor? These comments and mindsets are counterproductive and, frankly, depressing, and shows the lack of respect and confidence we have as a fraternity.

GPs are the heart and soul of primary care. Without the GPs, our healthcare model would crumble. Yet, GPs are not valued or validated.

Perhaps, if effective advocacy could be achieved to give doctors their rightful place and validation, especially in primary care, that would enable doctors to understand that it is okay and in fact better to delegate certain simpler tasks of business/clinical operations to colleagues we can trust and support, so that we can concentrate on those more complex and hard tasks we are trained to do.

As an analogy, no CEO of a big corporation does all the work themselves. GPs are the CEOs and the heart of the primary care network, and I believe they should be empowered and supported to play this vital role, rather than to continue to feel threatened by progress because of societal needs and the lack of representation.

3. Lack of integration

Being the CEO of an advocacy group representing 19 craft groups in the healthcare profession, in conjunction with my legal advocacy work as a law graduate, I have had the pleasure of attending various symposiums and exhibitions. Every time I walk into these, and although the craft-specific themes are amazing, I keep having these dreams and visions of one day having an exhibition of Australian Healthcare Professionals; a space where we can integrate, present and learn from each other’s craft. One that defines the best and most efficacious ways we can deliver healthcare to our patients and in conversation with our fellow peers in the trade.

This type of integration can be seen in the hospital system every day, where multidisciplinary teams get together with a clinical lead who governs the patient’s care needs and we derive the best outcomes for the patients.

Why can we not do this in the field of primary care? Or is this already being done, and perhaps the so-called turf war is in fact just an illusion that the higher political beings are creating?

In the line of work I do, we receive on a weekly basis inquiries and distress calls from various colleagues from various craft groups. Often, it’s because a healthcare worker has been pushed to notify a clinician for their shortfall – the chain of communication and mutual respect between colleagues has been severed.

It really does not have to be like this.

Notifications from patients is a whole different ball game, but when it comes to notifications among colleagues, notwithstanding the extenuating circumstances of mandatory reporting needs, it is always more traumatic and distressing for the person under investigation to know that their own peers “betrayed” them.

Sadly, most of these cases would have been solved with a simple phone call to the clinician seeking a peer-to-peer clarification. Rather, it often fuels the turf war theme even further.

My humble perspective is that the turf wars and power plays should be a theme of the past. Let us focus on the solution, one that most of us aspire to: validation, integration, efficacy and, most of all, happiness in practising our individual craft, ultimately seeing positive outcomes in our patients and in society.

Systems are set up by people; people can change, so can systems. Much work needs to be done in this space and one can only hope that in future we can leave behind these elements of negativity and concentrate on what is most important to ourselves and our patients.