The Australian Universities Accord recommends moves to stamp out ‘placement poverty’ in degrees with mandatory work components.

The government should work with tertiary education providers to lend financial support to students while they’re on placement, according to a weighty new report on the challenges facing Australia’s university sector.

Far from being an academic brain fart, the idea already has legs in the medical sphere.

The latest Australian Universities Accord has emerged from its 18-month gestation period with no fewer than 47 detailed recommendations designed to breathe new life into tertiary education.

Increasing the number of medical graduates from underrepresented backgrounds was one of the first recommendations listed, at number three.

The government was advised both to increase the number of new Commonwealth-supported places for medicine in areas of acute need and to provide funded places for all First Nations students who apply and meet the entry requirements for a medical degree.

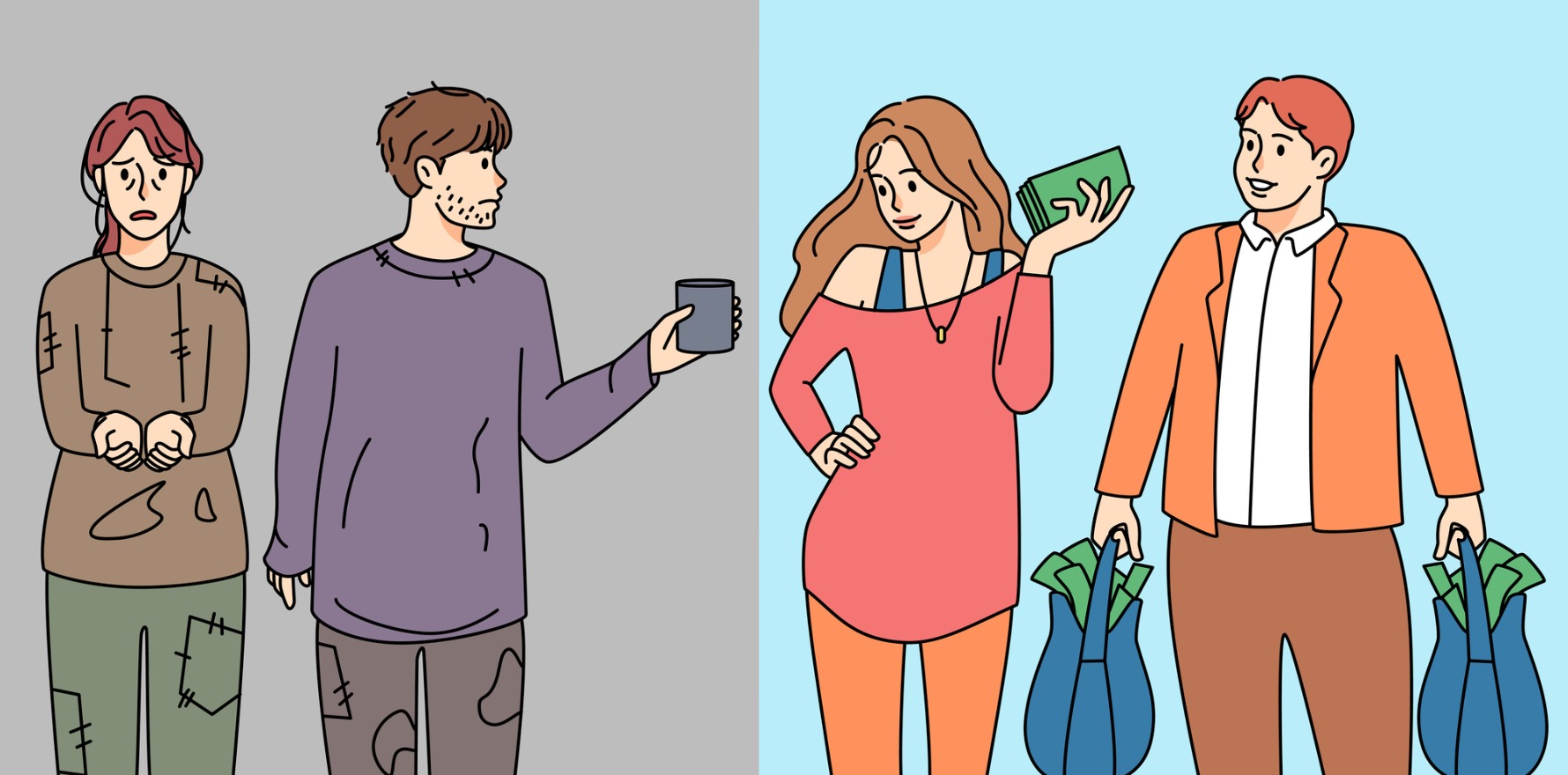

Coming in at number 14 was a recommendation to reduce the so-called “placement poverty” created by mandatory unpaid placements, particularly in the care and teaching professions.

“Many students have to forgo paid work to undertake unpaid placements and relocate away from home, leading to ‘placement poverty’,” the paper says.

“This results in poor early experiences in the workplace and negative perceptions of employment in the relevant industries, many of which are industries with longstanding skills shortages.”

Related

Coincidentally, the MJA published a perspective article just last week spruiking medical students as “a potentially sustainable solution for our workforce crisis”.

Western Health, which operates several public hospitals in Victoria, started a successful clinical assistant program in response to covid-19 which employs final-year medical students.

The students were paid $32.73 an hour and had their hours capped at 20 per week.

Their duties were limited to admin work and simple clinical tasks.

According to the authors, who were attached to the Western Clinical School at the University of Melbourne and the Victoria University Institute for Health and Sport, this is just the tip of the potential iceberg.

“Given the current workforce shortages and predicted required increase in skilled health care and social assistance professionals of 301,000 by 2026, clinical assistants have the potential to be an ongoing and sustainable workforce for an understaffed health care system,” the MJA article read.

Unlike junior doctors, clinical assistants are not bound by the rigidity of rotations and training structures.

They could act, according to the authors, as care navigators for older people and chronic disease sufferers, or bolster the medical presence in community aged care settings.

“Clinical assistants could also play a key role in primary care, mental health, and potentially as concierges helping vulnerable patients to access and navigate the health system in times of need,” they wrote.