Adhering to a protocol simply means the average person gets good care, but it also means the outliers are not helped and may be harmed.

The worst sort of interprofessional disagreement is where one side of the argument is about the evidence or outcome, and the other side is about the personal characteristics of the health professional.

It usually goes something like this. “I’m concerned that this project won’t get good outcomes for patients because it doesn’t deliver appropriate care”, countered by “you have no right to assert this because the people proposing this healthcare solution are highly trained health professionals”.

It has been so frustrating to have our genuine concerns about extended scopes of practice dismissed as “turf wars” or “gatekeeping”.

Anyone would think we have nothing better to do than undermine others, purely for our own professional gain, when if someone were able to reduce our waiting room load safely and well, I suspect we would all be grateful.

So, I wanted to ask, just this once, if we could look at a policy, and assume that everyone is a well-meaning health professional with a deep commitment to care before we assess whether this program delivers a good service for patients.

Here we have pharmacy undertaking a trial of antibiotic prescribing on the basis of symptoms alone. The important outcomes are those of the patient and the community. We want effective, efficient and accessible care for women with urinary tract infections and their communities.

Related

Unfortunately, the evaluation of the trial doesn’t tell us much about the outcome of this particular project, except that patients were satisfied, and there were no more drug side-effects than expected. But we do know what was done, and what the literature tells us. So, let’s look at the outcomes.

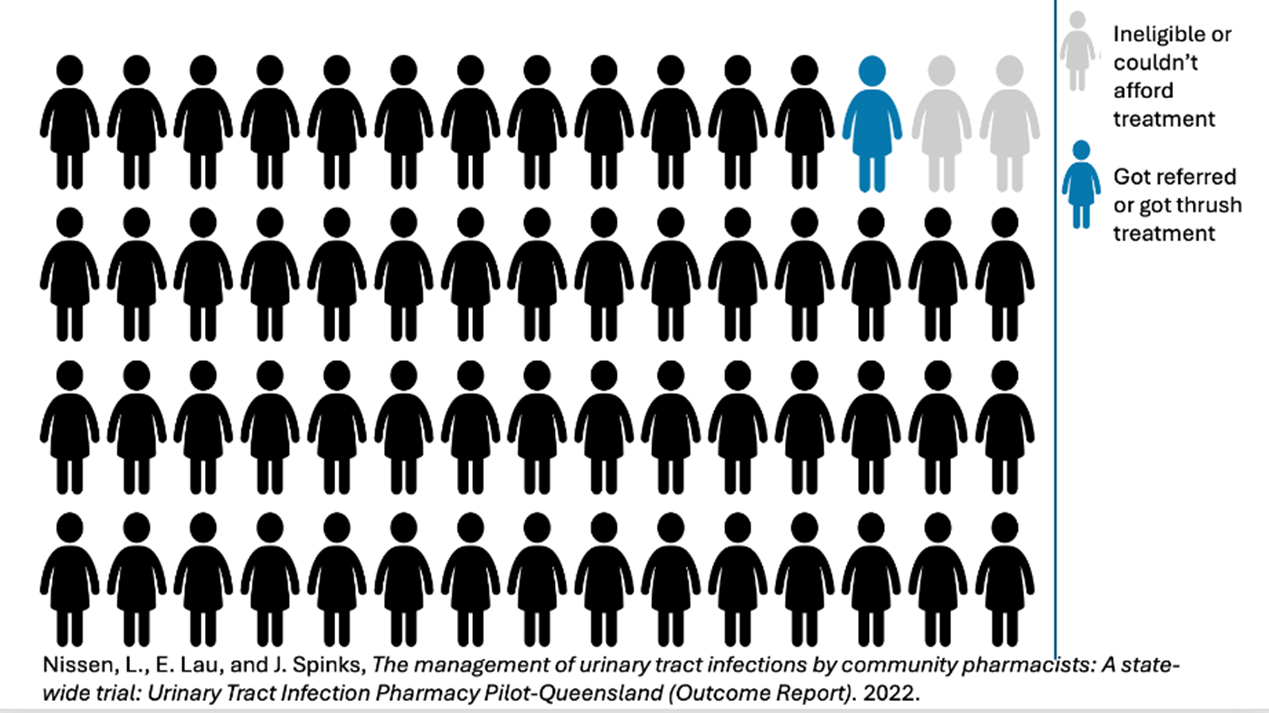

In total, 12,510 people approached the service for care, presumably because they had symptoms consistent with UTIs. About 800 decided not to proceed, many due to cost, or because they were ineligible. Some were given alternative over-the-counter treatments. The rest were given antibiotics.

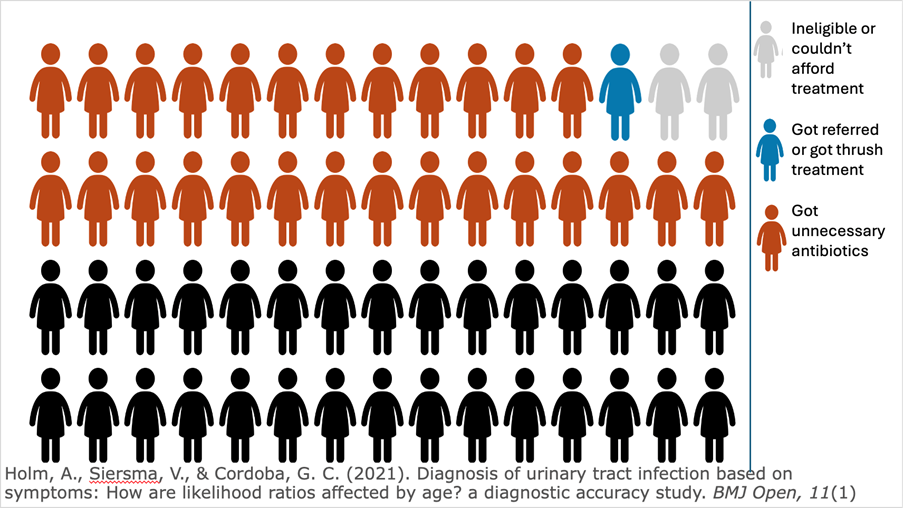

Based on the literature, we know that around 50% of women with classical UTI symptoms do not, in fact, have a UTI. This means that about 6000 women were given unnecessary antibiotics.

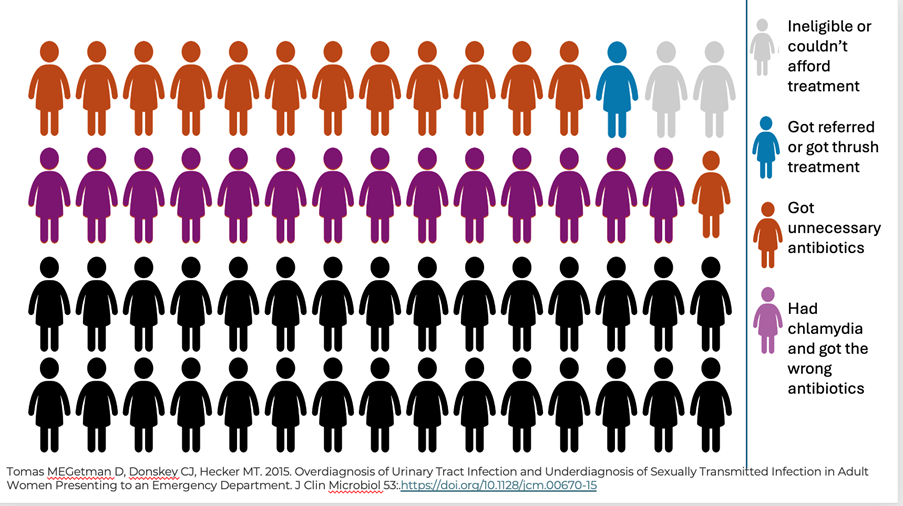

Based on the literature, we also know that about a quarter of these women were likely to have an STI. Unusually, the health professionals involved decided nine of the 12,500 women who presented were “at risk of an STI”, which I must say indicates a remarkably celibate population. This means that over a third of the women in the study got the wrong antibiotic, putting themselves and their partners at risk.

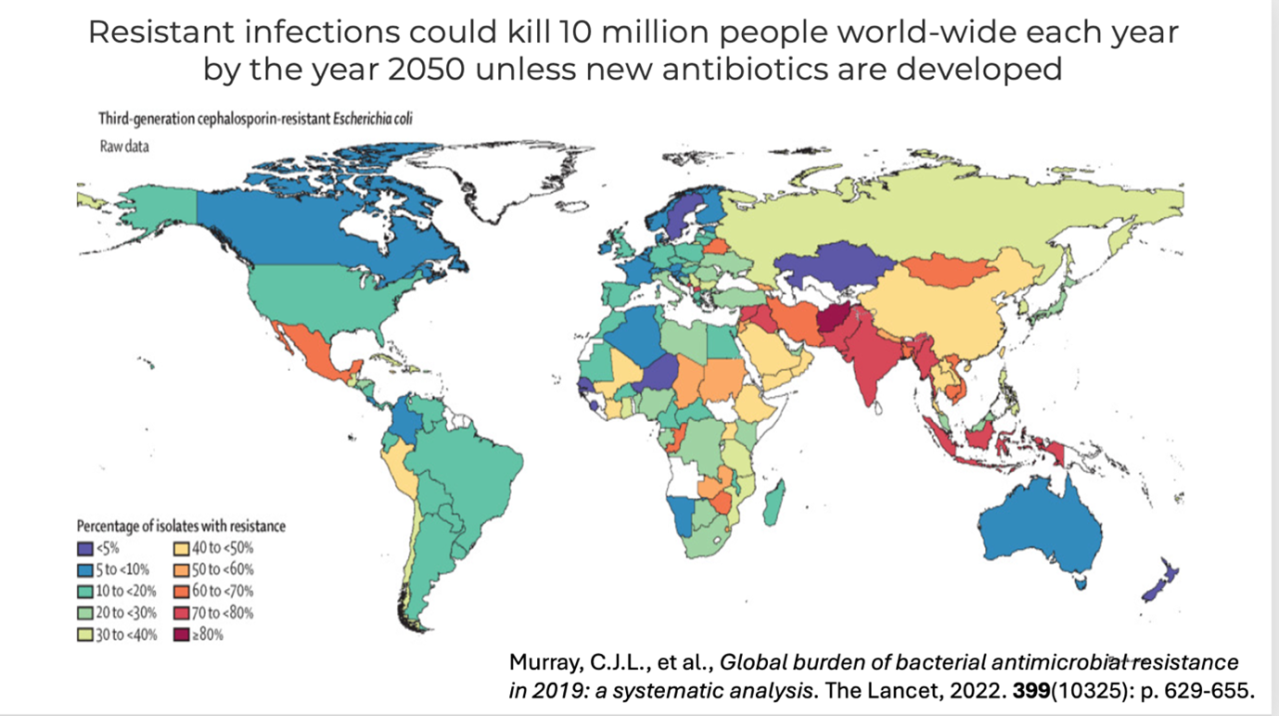

It takes approximately 11 days to develop antibiotic resistance. Which means we are likely to have more than 3000 women with resistant bacteria after this trial.

Many of our Asian neighbours have over 80% resistance to the antibiotics we use for UTI, giving them few choices for therapy. It is likely that we will follow this trend, which means we will increase hospitalisations for IV antibiotics. We are running out of oral options. The cost alone of IV antibiotics is prohibitive. The side-effects are significant.

Given this evidence, I think we have an issue. It is not good care for women, and it is not good care for the community. When I say this, the answer is usually (after “but they are highly trained health professionals”) that the pharmacists are following an “evidence-based” algorithm.

Adhering to a protocol simply means the average person gets good care, but it also means the outliers are not helped and may be harmed. Which is why following algorithms is not the same as clinical reasoning.

What’s worse is that the privileged people who can afford to access this service and pay the pharmacist are not the ones likely to die from an antibiotic resistant bug. It’s another case where the rich get the benefit and the poor wear the cost.

I know that the response to this argument is usually that I am a turf-warring GP who has some sort of moral or financial objection to a particular profession. Maybe I am and maybe I do, but that has NOTHING to do with this argument.

Clinical and population care in this trial wasn’t good enough. I don’t think the participant satisfaction due to convenience offsets that. I don’t care who the profession was, or what their motivation was. As a community, we can’t afford the cost.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.