A dystopian TV series has shown us that we are only as good (or bad) as we are pushed to be.

Sydney lockdown has finally ended after 15 long weeks.

Against all odds, we as a city have so far done remarkably well – with cases plummeting, hospitals calming down – as we ease restrictions (rather rapidly) and look forward to a new normal.

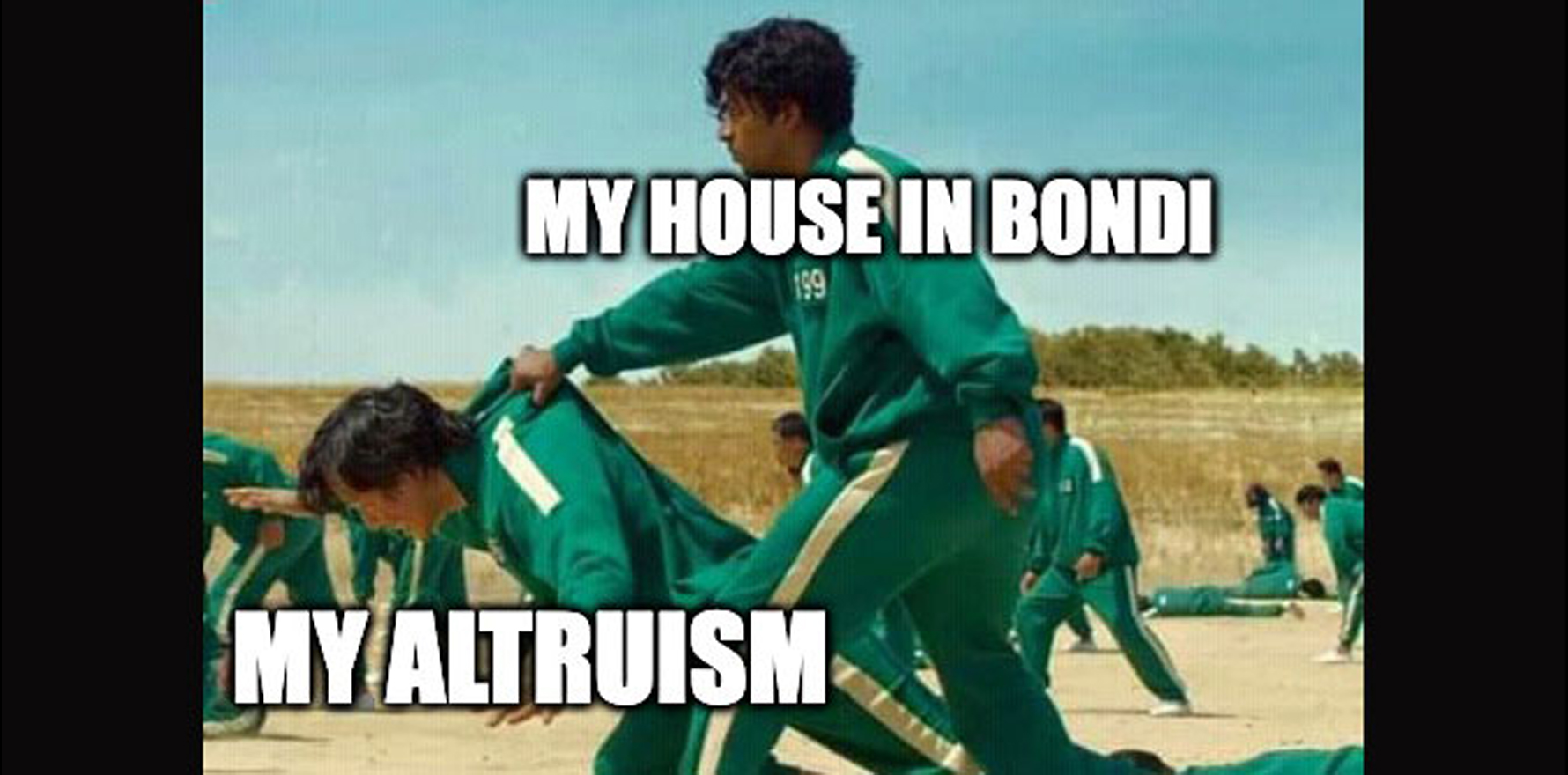

Unless you eschew TV altogether, or have been living under a rock, you are no doubt aware of Netflix’s #1 show and internet sensation: Squid Game. The basic premise, as in all dystopian genres, is of people on the brink of financial poverty and ruin making the choice to fight to the death, on the chance of leaving with millions of dollars.

In the days since I finished binge-watching the show, after my teens pushed me into it, we have been discussing its themes and greater meanings. Specifically how, when push comes to shove, seemingly good, kind and nice people will ultimately still end up choosing themselves first.

For me, the parallel to what we saw during Sydney lockdown – and in a somewhat similar, but less divisive fashion in Melbourne – is what I saw among peers, many of whom live in affluent parts of the city.

I used to be friends with many of these people, who were regularly posting change.org petitions, speaking out for helping those elsewhere in need, and all-around Good People.

When Sydney went into lockdown, however, and from my vantage view as a GP working and living in southwest Sydney, I began to advocate for my patients. Many of them were in the worst-affected local government areas (LGAs), with helicopters overhead till 2am, disrupting any chance of remote learning with their kids, unable to go out even to the park and stuck in two-bedroom apartments as a family of five or six.

Several of these peers became very defensive.

“Don’t judge, we are all suffering too.”

“Reporting someone just because they are on the beach in Bondi and mask-less is tribalism.”

“Read the room.”

“I am convinced some of the problems with these people is a lack of basic hygiene if they are getting it by going to Woolworths.”

On one group, I was reported multiple times and the post was eventually shut down. On another, the admin members themselves began arguing with me: “Some of us feel that … ” Eventually comments were shut down there too.

For me, the Sydney lockdown has been a surreal view into our own individual ethics and the ways in which we hide behind labels and defensiveness when confronted with facts and truths we don’t wish to see. In this case, I was led to believe that we were all equal, and dedicated and committed to caring for the genuinely disadvantaged.

I learnt, however, that this held true only as long as our own individual comfort was not at stake; for example, when the 5km rule came into effect, but in lower- risk LGAs, it meant an actual expansion of travel the breadth of the LGA, up to 30+ kilometres. Or when people earnestly and genuinely made arguments that beachside suburbs needed to go to the beach for their mental health and “people in SW Sydney need to stay in because you guys have the highest case numbers”. The irony was completely lost on them.

I was reminded of the parallel to Squid Game when one said to me: “I’m a good person, I donate money regularly, and we are not perfect, but there is no need to judge.” Again, without any hint of irony.

So in my discussions with my teens, when they speak of flawed characters, and how nice they thought they were and how it turned out they were wrong, it helps me to remember, now that the lockdown is fast becoming a distant memory, the truth is that we are only as good (or bad) as we are pushed to be.

Dying aside, when I am pretty sure most of us would choose ourselves first, none of us is probably as good, or altruistic as we like to think we are, until challenged. And then it is entirely likely that most of us would react with defensiveness and blame, instead of responding after reflection.

None of us likes to think the problem might lie with us, after all.

Dr Imaan Joshi is a Sydney GP; follow her @imaanjoshi