Everything we know about the new star of the covid show.

Omicron has made a stunning debut as the biggest diva on the pandemic stage.

The speed with which it has swept around the world has left researchers scrambling to get to grips with the B.1.1.529 variant. Here’s what we know so far.

Where did it come from, where did it go?

It took just over two weeks for the first confirmed case of B.1.1.529 infection in South Africa – diagnosed on 9 November 2021 – to turn into several thousand, and for Omicron to become only the fifth variant to earn the World Health Organisation’s designation as a variant of concern. Within a month, it had spread to at least 77 countries.

Omicron is now responsible for nearly 70% of global SARS-CoV-2 infections, including 94% of infections in the United Kingdom, 86% in the US and 77% in Australia.

It’s all in the genes

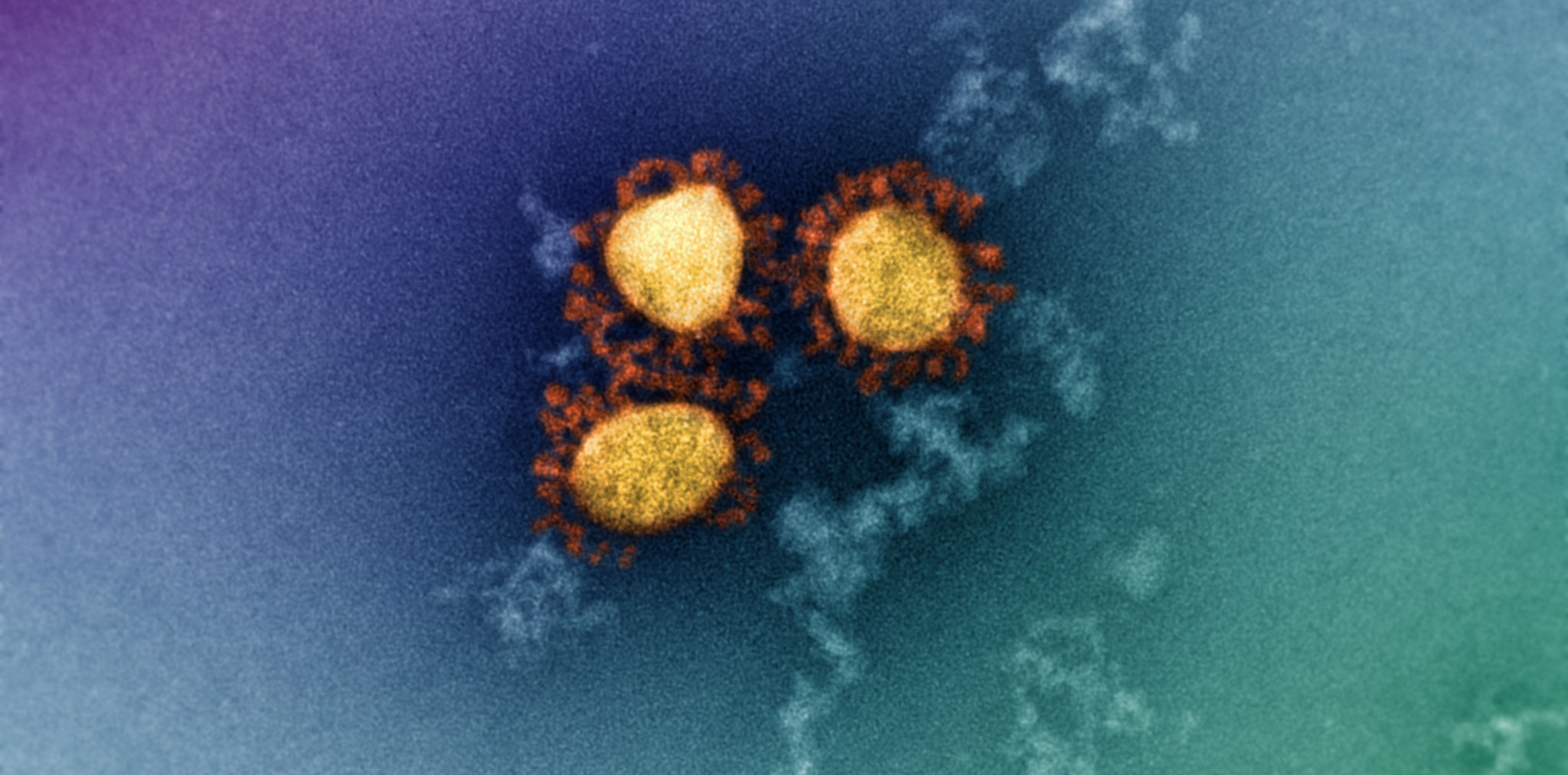

Omicron set an impressive new record among variants of concern for the number of mutations in its genetic code. Overall it has around 50 mutations but 30 of those are in the section of the genome that codes for the spikes on the virus’ surface, which the virus uses to interact with and gain access to host cells.

The reason this was originally – and now justifiably – cause for concern is because some of those mutations were in regions associated with how the spike protein binds to the ACE2 receptors on human cells, and potentially increased the strength of its bond with the ACE2 receptor, thus increasing its transmissibility.

The mutations also affect the ability of antibodies to recognise and bind to the spike protein, which means immunity developed from vaccines or previous exposure to an earlier variant may not be as effective at neutralising Omicron.

One particular mutation in the spike gene in Omicron gives a negative result in one assay in commonly-used RT-PCR test for covid – the TaqPath – and is distinctive only to Omicron, Alpha and a couple of minor variants. Hence this “S-gene target failure” has become the characteristic for identifying Omicron in testing.

Spreading like wildfire

The indicators of Omicron’s increased transmissibility were there very early on. On 8 December, a Christmas party of 111 attendees in Oslo – all of whom were at least double-vaccinated and had tested negative one to three days before the event – resulted in 80 infections among attendees and a further 60 infections in visitors to the restaurant later that day. Most, if not all, infections were likely Omicron.

Delta had a doubling time of around 11 days, according to the population-based REACT-1 study in the UK. The latest data from Omicron suggests its doubling time is around 1.5-1.6 days, and this is despite the more widespread vaccine coverage that exists with Omicron compared to Delta.

Unlike Delta, where the increased transmissibility was largely attributed to a much higher replication rate and viral load, Omicron may actually be associated with a lower viral load than Delta. The answer to Omicron’s higher transmissibility may be a combination of its increased affinity for binding to the ACE2 receptor on host cells, but also its ability to evade pre-existing antibodies.

This also has implications for the effectiveness of mask-wearing. The US Centers for Disease Control has updated its advice on masks to advise that well-fitted N95 or KN95 masks offer the best protection against Omicron.

How good is immunity?

The Omicron mutations that caused the greatest alarm when the variant was sequenced were those that might enable the variant to avoid neutralising antibodies derived either from vaccination or previous exposure.

The nightmarish prospect that the biggest vaccination campaign in human history might crumble in the face of Omicron has been partly realised – but mercifully there’s strong evidence that while vaccines may be far less effective at preventing infection, they still appear to be very good at keeping people out of hospital and out of the morgue.

Two doses of AstraZeneca or Pfizer offer barely any protection against symptomatic infection with Omicron, but a booster dose of mRNA vaccine offers around 55%-80% protection.

And for those who think previous infection with Delta will keep them safe from Omicron (*cough* Djokovic *cough*), population-based data from the UK suggests that the risk of reinfection with Omicron is more than five times higher than it is with Delta.

Testing, testing

One particularly annoying feature of the new variant is its apparent ability to slip past rapid antigen tests in the early days of its infectious period, and to be less easily detected in nasal swabs than in saliva, according to early, preprint research.

‘Less severe’ or ‘more mild’?

Omicron does appear to be less likely to cause severe illness or death, but it’s not yet clear whether that’s the result of vaccination or the disease itself.

One of the earliest studies from South Africa, which does not have high vaccination rates, found that hospital rates were lower during the early Omicron outbreak, even while case rates were higher. It also suggested that around 28% of patients developed severe disease during the early Omicron period, compared to 60% during the Beta variant wave and 66% during the Delta wave.

Another study from the US suggested the risk of admission to emergency department was 70% lower with Omicron than with Delta, the risk ICU admission was 67% lower and the risk of mechanical ventilation was 84% lower, even after accounting for factors such as comorbidities and vaccination status.

And in the UK, where Omicron has run rampant even in its highly vaccinated population, population-based data points to a 20-25% lower rate of any hospitalisation with Omicron than with Delta, and a 40%-45% lower rate of being in hospital for at least a day. But the authors of that study warn that this has to be balanced against the increased risk of infection with Omicron, even among the vaccinated.

But the glimmer of good news is that while evidence suggests a double-dose of AstraZeneca offers relatively little protection against mild infection, it still holds fast against more severe outcomes.

Main image: Omicron negative stain image created at the Doherty Institute