This is confusing.

Apologies to any readers with obsessive-compulsive disorder that manifests in hand washing. This one’s going to hurt.

The importance of hand washing for doctors has been known since the mid-19th century – thank you, Ignaz and Florence.

The importance of hand washing for the general population has been well and truly known since 2020 – thank you, SARS-CoV-2.

What is, apparently, not known is how to keep the places where we perform this sometimes lifesaving activity free from “communities” of the potentially pathogenic filth we wash off, according to this Australian paper in Science of the Total Environment.

Calling hospital and home handbasins an “underrecognised source of infections”, the authors point that infection control guidelines tend to focus only on hospitals at a time when more and more care is being delivered in the home to reduce the burden on healthcare systems.

The team set out to investigate and compare “the bacterial diversity of biofilms formed on faucets and drains of handwashing basins present in a hospital and residential buildings”. They collected 40 samples from basins and taps in 11 South Australian homes and one NSW hospital and extracted and analysed DNA.

They found a total of 90 archaeal and 4079 bacterial “operational taxonomic units” including 250 bacterial phyla, the most common being Pseudomonadota, followed by Bacteroidota, Planctomyetota, Actinobacteriota and Verrucomicrobiota.

None of whom sound like the kind of folks you want gatecrashing your cleaning party.

There were seven pathogenic, 12 potentially pathogenic and 38 potentially corrosive genera, and 20 with “strong biofilm forming capabilities”. Biofilms, the authors write, “provide refuge and protection from environmental conditions for genera that may not survive in planktonic form resulting in the survival and proliferation of diverse communities”.

Of the “opportunistic premise plumbing pathogens” identified, Legionella was the only one more common in residential than hospital samples.

Plenty more bugs were uncultured or unclassified, so the real number of pathogens could be much higher.

Drain biofilms had significantly more of the taxa Pseudomonas, Chryseobacterium, Delftia and Microbacterium, whereas Methylobacterium-Methlylorubrum was more abundant in taps. Home basins had more Legionella, Bosea, Sphingomonas, Flavobacterium, Acidovorax and Delftia, while Staphylococcus was the only pathogen more plentiful in a hospital basin.

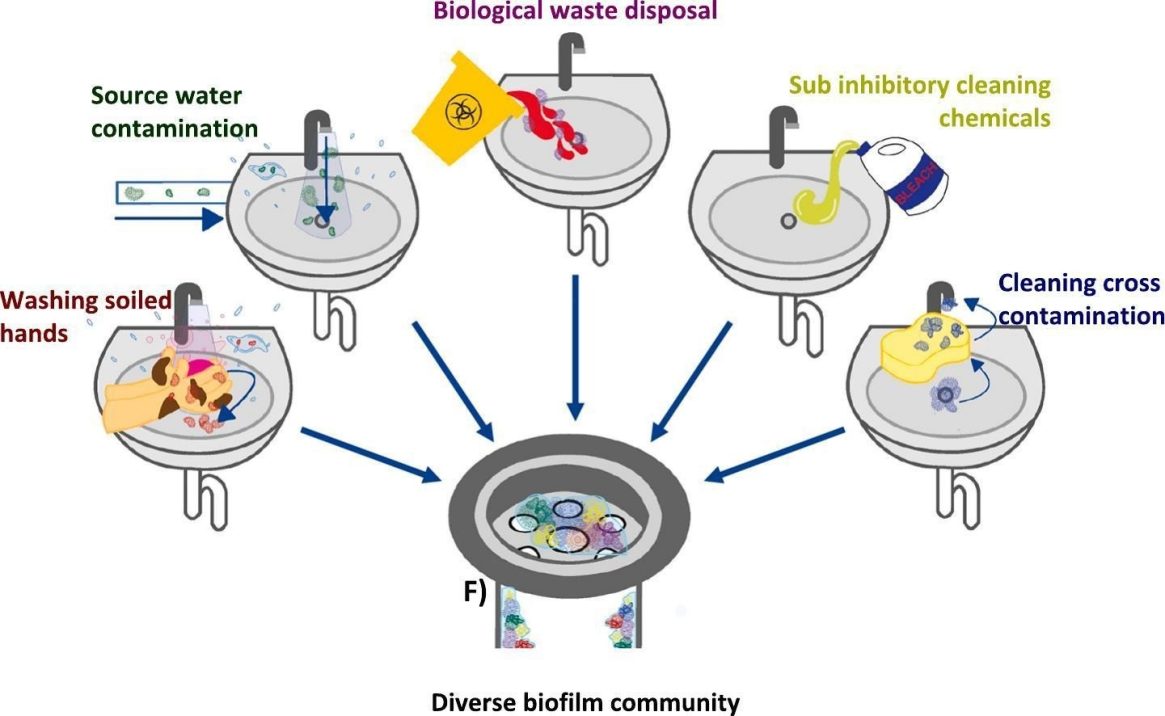

How do they all get there? Well:

While residential basins may be used to wash off soil from the garden, hospitals have other obvious sources of potential contamination. The authors cite an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Korean cardiology ward that was traced to someone putting contaminated dialysis fluid and human waste into a handwashing basin.

Yuck.

Current hospital infection control guidelines “overlook drinking water and water-related devices as a source of these bacteria, focussing instead of dry high touch surfaces and medical device”.

Even when guidelines do recommend cleaning basins twice a day, the authors note that cleaning different surfaces with the same cloth can transfer microbial communities – and what cleaning staff, realistically, is using different cloths for every surface every time?

As for residential infection control guidelines, there aren’t any.

Certain aesthetic designs like “under mounted basins, water saving low flow faucets and linear trench style drains” may encourage biofilm growth. The Back Page will not hold our breath for “low-biofilm” designs to start populating home renovation media.

All of this makes us want, and not want, to go and wash our hands.

Send vats of hand sanitiser to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.