Up until very recently, there has been no advocacy group in Australia for people with obesity. Doesn't that strike you as odd?

Soon after the first HIV cases were diagnosed in Australia in the 1980s, the gay community rose up against “AIDS hysteria” and demanded better healthcare.

Activists quickly formed networks, called public meetings and lobbied governments. AIDS councils were set up in every state by the mid-80s.

Thanks to these sustained advocacy efforts over decades, antiretroviral and PrEP drugs don’t cost patients a fortune, and HIV stigma is itself stigmatised, at least in politically correct society.

Likewise, the battle against diabetes has been hard fought by those who have the most to lose from staying silent – patients and their families.

Australia’s first Diabetic Association was formed in 1937, and there are now 134,000 paid members of state-based groups, many of whom are patients themselves.

In fact, it’s hard to find a single medical condition where people haven’t banded together to cut a better deal with government and society … except when it comes to obesity.

Until six weeks ago, there was no organisation that you could join as a person with obesity to publicly advocate for your healthcare rights in this country.

Seems strange, doesn’t it?

What you do see are lots of obesity organisations being founded and run by well-meaning – but almost exclusively skinny – healthcare practitioners.

One such group, The Obesity Collective, has helped form the first ever consumer advocacy group for people with lived experience of obesity in Australia – the Weight Issues Network (WIN).

WIN launched six weeks ago and now has more than 100 members.

There is a “desperate need” for a consumer advocacy group in obesity because weight discrimination blocks access to healthcare, says Professor John Dixon, an obesity expert at the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute.

“So much of the public health messaging is bound up in ideas that are contrary to the biology,” he says.

“They are being basically told, ‘Stop it. Just stop it. Don’t increase your weight’. Well, that doesn’t help people with the lived experience of obesity.”

We know that sustained weight loss is incredibly challenging, and yet obesity drugs aren’t on the PBS and the wait list for bariatric surgery is years long, says Professor Dixon.

The underground anti-dieting movement

Even though the rate of obesity has more than doubled in Australia since the 1980s (and now affects 31% of Australian adults and 25% of children), it’s hard to hear the voices of people with high BMIs anywhere in the media.

“Fat activists” are extremely rare in this country. A few, brave comedians, models and bloggers have spoken up about their experience of being plus-sized, only to be shouted down by trolls and tabloid newspapers such as Sydney’s The Daily Telegraph.

Kath Read, the Brisbane librarian who ran the “Fat Heffalump: Living with Fattitude” blog for 10 years, has bowed out of the public discourse.

Her final blog post reads: “I’m tired of giving my life to people who won’t even stand up to their own families, friends and colleagues in the face of hatred and bigotry, who then whinge that I’m ‘doing it wrong’. It’s someone else’s turn. I’m done. I’ve got a life to live.”

However, it’s hard to imagine that most people with BMIs greater than 30 – which is more than one-third of Australian adults – are remaining completely silent on issues like weight discrimination.

And they aren’t. They’re mostly just talking to each other in safe spaces online.

Take the 40,000 member-strong Facebook group called The Moderation Movement.

This is a closed group where people with larger bodies privately swap personal stories, clothing tips and advice on how to stand up to pushy doctors. This group is part of a global social movement, called Health at Every Size (HAES), which rejects weight loss as a health goal.

HAES advocates believe people with obesity should be accepted for whom they are, and that it is both immoral and impractical to attempt to eliminate this group through weight-loss programs.

HAES is firmly against dieting. Instead, it promotes an intuitive approach to eating where no foods are restricted, and people are taught to respond to their appetite cues, with a mind to nourishment, enjoyment and health outcomes.

Whereas the RACGP, the AMA and The Obesity Collective emphasise the fact that obesity is a major risk factor for chronic disease, HAES Australia believes weight should not be pathologised.

HAES Australia was founded in 2013 and its elected board of directors currently consists of two dietitians, a clinical psychologist and an occupational therapist, none of whom are obese themselves.

The organisation has an advisory council of people with higher BMIs, but the most visible members are slim healthcare practitioners.

Fiona Willer, a dietitian who is on the management committee at HAES Australia, says people with higher BMIs are “very out there in these closed Facebook groups” but there’s a great deal of personal social risk associated with speaking their minds publicly.

Telling the world that you are not going to try to lose weight anymore can risk relationships, she says. This can be devastating when care is conditional upon continued attempts to lose weight.

A familiar story

People with obesity are instructed – often at every GP appointment – to diet and exercise, but most people with obesity fail to keep weight off over five years using these commonsense interventions.

The human body is physiologically hardwired to bounce back to its baseline weight, according to the NHMRC’s 2013 clinical guidelines.

For some people living with obesity, dieting often feels like a cycle of self-abuse followed by failure.

That’s the story that Fiona Tibballs from Melbourne tells me over the phone. Ms Tibballs is a member of The Moderation Movement Facebook page. Doctors would classify her as obese.

“All my life I was either on a diet or feeling guilty because I wasn’t a diet,” she says.

She has only ever reached her goal weight once and she stayed there for precisely six weeks before putting the weight back on.

“For the last 20 years, I’ve been losing and gaining the same 10 kilos,” she says.

After joining Weight Watchers for something like the 25th time, Ms Tibballs went to see a HAES dietician who said that dieting wasn’t the answer.

“And I actually got quite angry at the time because she’s a very slim woman and I thought, ‘What would she know about it? I’d live on a diet of chocolate if I ate intuitively’,” says Ms Tibballs.

But she did some research and gradually came around to the idea.

Now that she’s not actively dieting, her relationship with food is much healthier, she says. “Chocolate will sit in the fridge for days sometimes even weeks” instead of being part of a pre-diet binge, she says.

Since adopting a freer, more relaxed attitude to food, Ms Tibballs says her weight has gone up but that she is more active, eating more fruit and vegetables and feeling happier.

Her latest blood tests show her cholesterol and blood sugar are down.

Kelly Gates, a personal trainer based in Sydney and a member of The Moderation Movement Facebook group, developed an eating disorder when she was 19. It lasted 10 years.

“I was in hospital, out of hospital … I was so weight focused,” she says.

When she recovered from anorexia at the age of 31, she began to put on weight.

“And every time I went to a doctor, they were always harping on about losing weight, but then I had an eating disorder. So why would you tell someone that had an eating disorder to lose weight?”

Ms Gates says she prefers HAES because it’s less harmful than the weight-centric approach.

“As soon as I stop dieting, I forgot about my weight,” she says. “I was just eating. I was just literally exercising three times a week and my weight just stabilised.”

Who will WIN?

There’s a war brewing between HAES Australia and the Weight Issues Network.

Both want to position themselves as the go-to representative body for people with obesity, but they have fundamentally different ideas about what their members want.

The rivalry has already started to turn ugly.

In a podcast episode earlier this year, HAES Australia dietician Mandy-Lee Noble and clinical psychologist Louise Adams ridiculed The Obesity Collective’s efforts to empathise with people with lived experience of obesity.

(All Fired Up! is a podcast associated with UNTRAPPED, a business that runs programs based on HAES philosophy. These programs cost between $570 (for three months) and $2,750 (for a retreat). Louise Adams and Fiona Willer are both UNTRAPPED guides. Psychologists, dietitians and personal trainers can sign up to become affiliates of UNTRAPPED, and “any time a client of yours signs up to the program you’ll receive a generous payment. The more clients you sign up, the more payments you can collect,” the website states.)

HAES Australia has also scrutinised The Obesity Collective’s ties to pharmaceutical companies.

“The pharmaceutical industry has a vested interest in framing body weight as a disease so that it can be treated,” says Dr Carolynne White, the president of HAES Australia and an occupational therapist.

“I wonder about [The Obesity Collective’s] motives in terms of the people that they’re bringing together.”

Since The Obesity Collective launched last year, it’s received funding from:

- NSW Health ($150,000)

- Bupa Health Foundation ($400,000)

- PwC Australia

- The University of Sydney ($250,000)

- Johnson & Johnson, a major manufacturer of obesity surgery devices ($5,000)

- Novo Nordisk, the creator of anti-obesity drug Saxenda ($32,000)

- Amgen Australia, a company investing in anti-obesity R&D ($40,000)

- Fitbit, a market leader in fitness wearables (plans to donate trackers)

So, less than 10% of The Obesity Collective’s current funding is linked with ‘treatment’ industries.

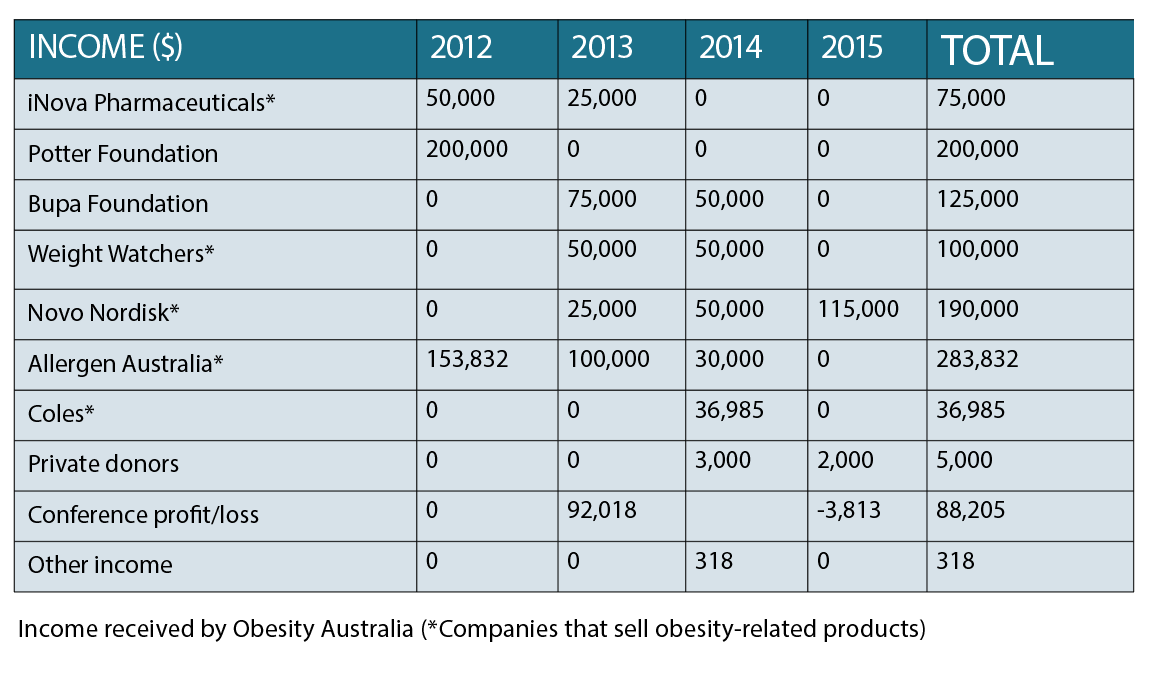

Obesity Australia (which has the same ABN as The Obesity Collective) has received over half a million dollars in funding from pharma companies, including $283,832 from Allergen Australia, which makes lap-bands.

By comparison, HAES Australia does not accept any money from sponsors. It is a not-for-profit that is 100% funded by membership fees.

Finding common ground

WIN had its first workshop in April and has only just started accepting new members, so it’s a little too early to pass judgment on the group.

But, from my 45-minute phone conversation with two members of the WIN advisory board, I got a sense that WIN is really trying to do this the right way.

The network is being supported by The Obesity Collective through volunteer work, but it has an independent board that will make its own decisions about who to approach for sponsorship.

The WIN board is mostly made up of people with lived experience of obesity who have few conflicts of interest.

Lyn Keppler, the Indigenous representative on the board, describes herself as a retired schoolteacher, businesswoman, mother of three and grandmother of 14.

“I’ve suffered obesity most of my life, since the age of five,” she says.

Ms Keppler has had surgery twice to treat her obesity.

“From that have lost 45 kilos. I have regained my mobility. I’ve gone from being on a scooter and a walking frame to now having no aids at all. And I’m back dancing and doing rock and roll. I hadn’t done the dancing for nearly 20 years.”

WIN is about fighting stigma, something that Ms Keppler has suffered first-hand. It’s also about providing evidence-based education on obesity, she says.

Divya Ramachandran, another member of the WIN advisory board, tells me that she doesn’t identify as a “patient”, but that she was born with obesity.

Ms Ramachandran never really faced weight stigma as a kid because she was seen as “cute” and was cast in “all the comic roles”, she says.

“Until about 10 years ago, I didn’t connect my weight with my health,” she says. “Weight was just a thing. It wasn’t central in my life.”

After the birth of her daughter, however, she started to recognise the health risks associated with obesity.

She tried many diets, “some very detrimental, some very restrictive” and found it almost impossible to get tailored weight-loss advice, she says.

“And mind you, I’m highly educated, well-qualified and not easily fooled,” she says. “The information out there is just not evidence-based.”

Tiffany Petre, the director of The Obesity Collective and former PwC consultant, also joins the call. She’s not on the WIN board but she’s helping the group get set up, she explains.

In the next year, WIN wants to media train people with lived experience of obesity so that they feel comfortable and safe telling their stories in public, she says.

I ask her whether HAES activists would be welcome at WIN.

“I think we have aligned interests around reducing stigma,” she says. “We’ve all experienced struggling with diets and the pressure and misinformation. So, I think the body positivity people are making a lot of progress in that space and I think it’s valuable.”

People who aren’t interested in losing weight should be “100% respected”, she says.

At the same time, we need to recognise the many people with obesity who are actively trying to lose weight; “There are people that want help”, she says.

It’s also unhelpful to ignore the links between adiposity and chronic diseases, she says.

For full disclosure, I’m a skinny medical journalist who has never had to worry about my weight. I don’t have any relevant lived experience to draw on here.

But my day job is all about finding untold stories, so it would be nice to see a few more media releases shaping a healthier public conversation around obesity in my inbox, next to those hundreds of emails about HIV and diabetes.

The bottom line is this: you’re not really offering healthcare if patients aren’t interested in accepting it.

And the absence of a consumer advocacy group means there’s very little public information about what people with obesity actually want.