Taking a child’s temperature has become a habit. But how often is it really necessary? asks Dr Michael Fasher

Do you need a thermometer when assessing febrile children between six months and five years old in general practice?

I think not; at least mostly not.

In our well-immunised population, there is a low prevalence of invasive bacterial disease. Thus most children in the community with a high temperature will have a self-limiting viral illness. Some will have a viral illness that results in admission to hospital; some will have a bacteraemia that progresses to invasive bacterial disease. Predicting the outcome is rarely possible after the initial history and exam.

Knowing the precise temperature at the time of consultation does not resolve the dilemma.

A child with a temperature of 37.8°C needs the same safety net as that provided for a child with a temperature of 40°C.

The concept of “precise temperature” in the community is problematic. The reading recorded depends on the instrument used, the operator and the body site selected for the measurement. Compounding these issues, temperatures fluctuate.

Taking and recording the temperature provides no guide to the next steps. A parental history of fever is all that is needed to trigger construction of a safety net.

Note that in hospital the situation is quite different. In hospitalised children, serious febrile illnesses are more common than in the community, and generally the measurements are made with one kind of thermometer at the same body site and charted to illustrate trends.

Temperature charts are an important element of the successful strategy, “between the flags”.

In general practice, the thermometer is sometimes helpful.

A focused history is needed to establish how long the child has been febrile. This should be followed by a search for symptoms of common febrile diseases and relevant features.

The length of the illness is important because in most febrile pre-schoolers the fever resolves by day four. If fever persists beyond then in a well looking pre-schooler, the provisional and differential diagnosis should be revisited. Most will still be viral but Kawasaki, atypical pneumonia, and UTI in younger children demand consideration.

At the back of the doctor’s mind lies the thought that not all fever is a result of infection. Young children do get cancer, rheumatologic disease, not to mention relapsing fever syndromes.

Parents need to leave the consultation crystal clear on the features that demand formal review. As we have seen, persistence of fever into the fifth day is one of these.

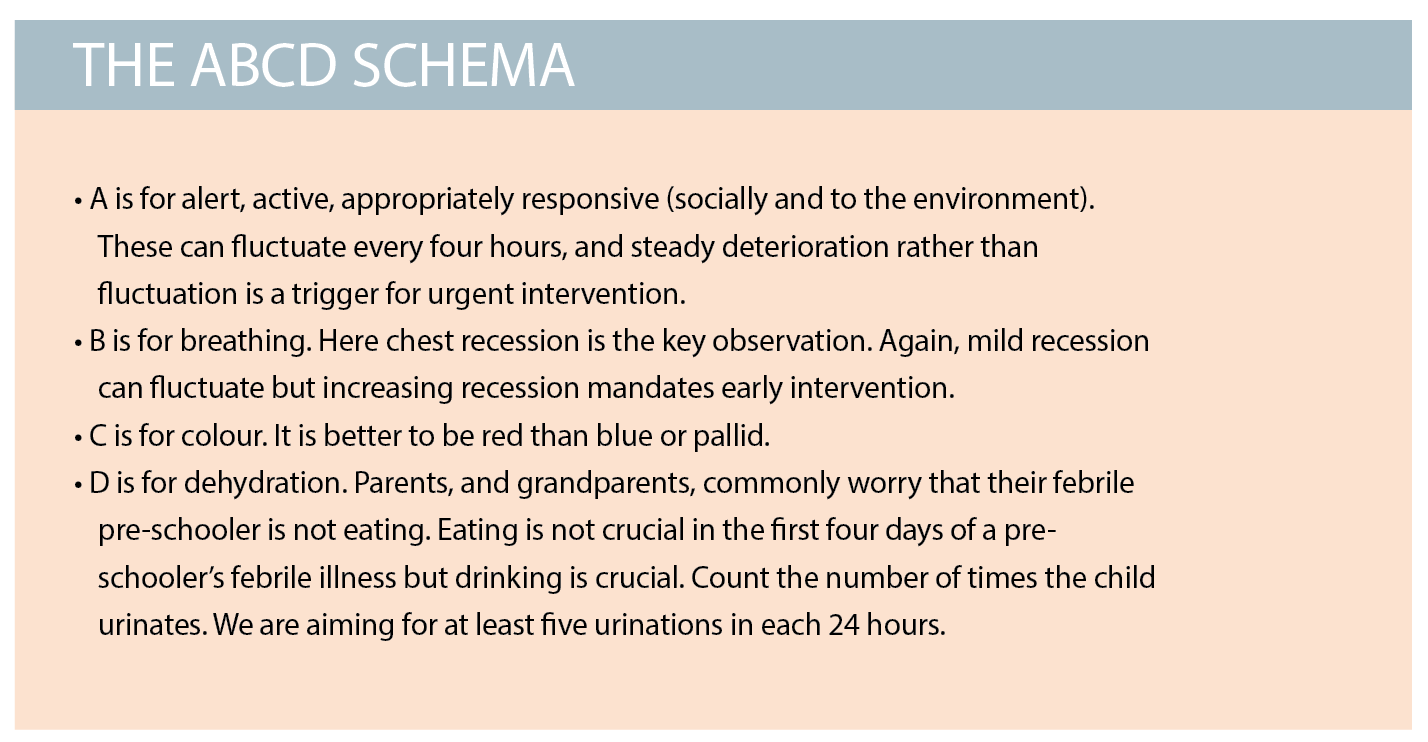

Next, parents need to become confident and competent in monitoring crucial symptoms and signs during the four days of fever.

One way of expressing these crucial observations is by the ABCD schema (See box above).

You will note, none of these crucial observations includes taking a temperature. Taking a temperature is a habit. It runs the risk of fanning fever phobia and distracting from the important ABCD observations.

Managing coughs and colds is rewarding. Building parental confidence and competence visibly improves family functioning – a privilege and great reason for coming to work.

Parents need to leave the consultation crystal clear on the features that demand formal review.

Although not highlighted here, an essential clinical skill needed to achieve these outcomes is empathy. Empathy is needed early; empathy is needed often. Be sure to understand why this child and this family have come to see you today.

Michael Fasher is Adjunct Associate Professor at Western Sydney University