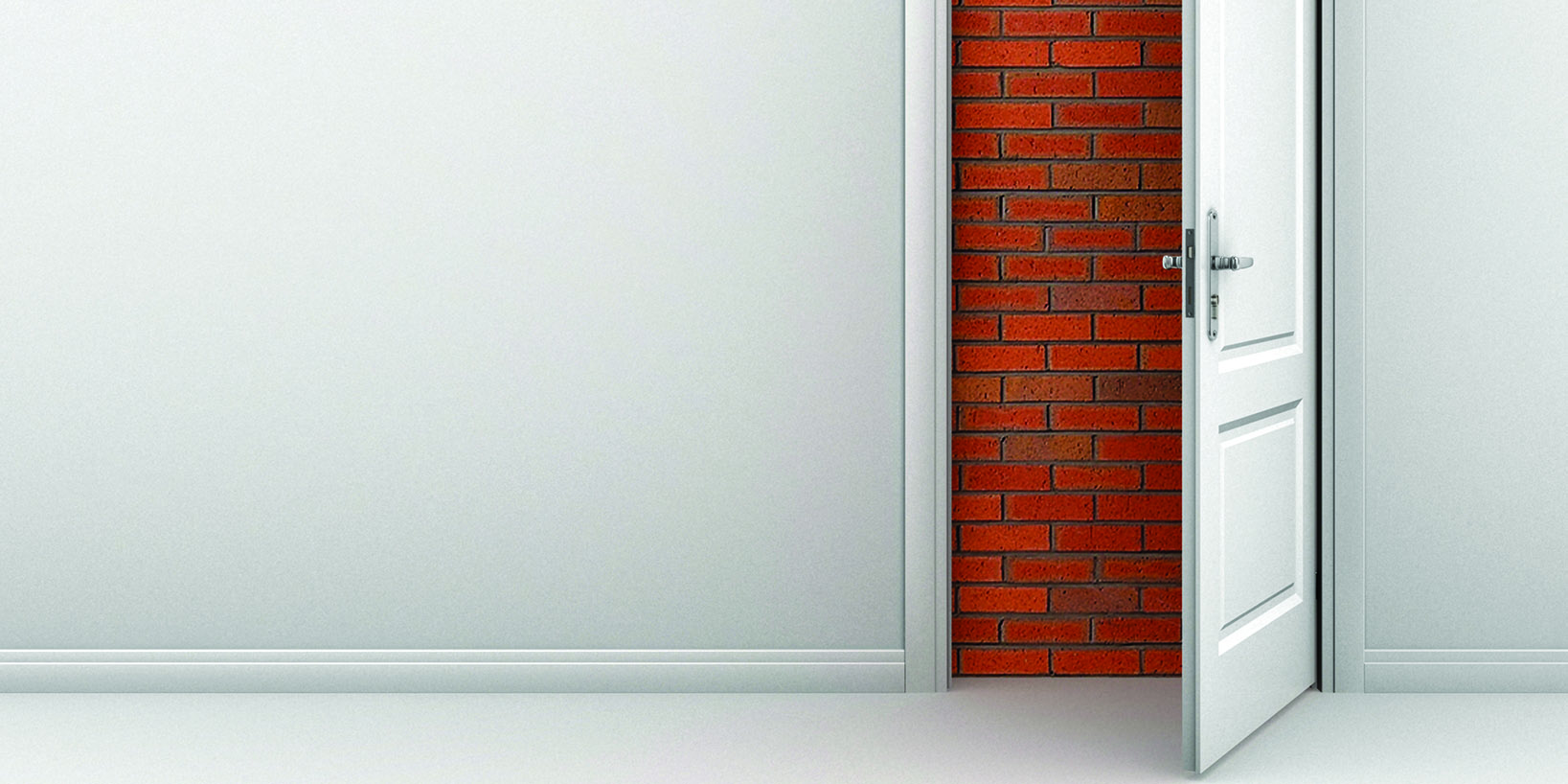

Students with disabilities are beating on the doors of medical schools. Why is it so hard for them to get in?

“It always seems impossible, until it’s done.” – Nelson Mandela

There was a time in the US when wheelchairs had to be manually lifted from the street to the sidewalk because there were no curb cuts.

In the 1970s, a band of UC Berkeley’s students with quadriplegia – who called themselves the Rolling Quads – protested until the local council agreed to cut ramps on every street.

Elsewhere across the country, demonstrators in wheelchairs took sledgehammers to pavements. And, bit by bit, they chipped away at discrimination.

As soon as the curb cuts were made, it became obvious that they were useful to everyone, not just those with significant disabilities.

A curb cut is just a practical, alternative pathway. Once in place, a world without them becomes unthinkable.

MAKING THE CUT

Gaining entry to medical school is fiercely competitive in Australia, and most students have to ace a five-and-a-half-hour exam to even be considered for a spot.

For Jerusha Mather, a PhD candidate at Victoria University, the rigid application process is the modern-day version of an uncut curb. It’s an unfair barrier stopping her in her tracks. Mather desperately wants to study medicine, but she has cerebral palsy and is put at a distinct disadvantage in a timed, written exam due to her handwriting capacity and mild speech difficulties.

“It’s not like a university exam that’s testing prior knowledge; the GAMSAT is testing problem solving and you need to be able to annotate,” she said.

“Even when a scribe is provided, they cannot accurately scribe what I’m saying because of the complex nature of knowledge that’s required. It’s hard to do the GAMSAT in your head. It’s a very unrealistic expectation. You lose marks by losing time.”

The 24-year old has managed to complete biomedical sciences honours at RMIT University. She’s now researching non-invasive brain stimulation as a potential treatment for cerebral palsy as part of her doctorate.

She’s a distinction-average student with glowing recommendations from past lecturers. “I know Jerusha will relish this opportunity and become a great doctor and a positive inspiration and a role model to many,” wrote one referee.

Mather has taken – and failed – the GAMSAT twice because she wasn’t given adequate accommodations.

She’s been fighting tooth and nail to get allowances that might put her on a level playing field. But her request to sit the GAMSAT over several days was refused by the ACER on the basis that it would compromise the integrity of the exam. In 2016, she took her case to the Australian Human Rights Commission, but was unsuccessful.

Mather’s condition doesn’t affect her cognitive abilities. But she has involuntary movements and has trouble walking on uneven ground. Her speech is laboured at times, but she is very articulate in writing.

“I do foresee challenges,” Mather replied in an email. “But I believe I have the will and determination to overcome them.

“I would choose a specialty that aligns with my abilities, such as pathology, radiology, rehabilitation medicine or general practice.”

If her dream becomes a reality, Mather’s future workplace might look a little different to a standard doctor’s practice. She’d require a clinical assistant that could help with interpretation and notetaking, adaptable medical equipment and electronic medical records and forms.

But she wouldn’t be the first person with cerebral palsy to practise medicine.

Dr Tom Strax, a physician based in New Jersey in the US, has built a distinguished clinical career in rehabilitation medicine despite his significant speech and mobility challenges.

Dr Strax was diagnosed with athetoid cerebral palsy as a child in the 1940s. It was a different time back then, with very few opportunities for people with disabilities to live a normal life. In fact, when he was born, the delivering doctor said: “This baby is better off dead.”

Discrimination followed Dr Strax through his student years. “How dare you apply to medical school when there are all these able-bodied people waiting to get in?” was a comment he received from one admissions officer.

But his family was very supportive (and well-connected) and pulled as many strings as they could to get him into New York University School of Medicine. There he learned how to use tools such as the Kelly Clamp to help with dissections and the vacutainer to draw blood. On his obstetrics rotation, he delivered 14 babies. He graduated in 1963.

Dr Strax is a fierce advocate for disability rights. “Here are some facts,” he wrote in an email to The Medical Republic.

“I served six deans in three medical schools as a department chair, training hundreds of residents. Fourteen went on to become professors. I was a chief medical officer. For years, I was the consultant for our National Board of Medical Examiners. I was at the White House for the Americans with Disabilities Act signing.”

Quite a list of achievements for someone who would probably be unable to study medicine in Australia in 2019.

SILENT MINORITY

Mather is not alone; there are other prospective medical students out there with disabilities. These students had learning disabilities, ADHD, physical disabilities and anxiety and shared their stories confidentially with The Medical Republic on the understanding that identifying details would not be published.

One student said a high-pressure interview could trigger anxiety, which would put them at a disadvantage compared with their peers. “It’s unfair because in real life I’m a confident speaker,” they said. “But when you’re in an interview and your whole life depends on 30 minutes, it triggers off anxiety, which clouds your thinking and causes you to score poorly.”

Another student, who gave up on trying to get into medical school for fear of employment discrimination, said: “People are almost desperate to find reasons why a prospective medical student with a disability shouldn’t give it a go, rather than taking the time to look deeply into the student’s individual capabilities. This culture should change.”

“It’s very, very frustrating,” one student said. “The second you mention learning disability, you will not get a job in medicine and you will be discriminated against.”

FEELING UNWELCOME

We all want doctors who are intellectually and physically capable of doing the job, and who reflect the diversity in the community in terms of gender, age, race and rurality. But when it comes to training doctors with disabilities, Australian medical schools are often closed-minded.

Instead of welcoming students with disabilities, the Medical Deans of Australia and New Zealand have produced a very specific list of inherent requirements that they deem necessary to complete a degree in medicine.

Although the self-declared aim of the document is to provide “the greatest access for students with a disability while ensuring safe clinical training”, the 2017 version of the guidelines has a distinctly unwelcoming vibe if you’re a student with a significant disability.

The guidelines state that medical students must be able to undertake the course full-time, should graduate with the ability to perform CPR, must be capable of reading fine print, must be able to perform a full physical examination, and must possess one fully functional arm, among other requirements.

The document was “potentially discriminatory” towards students with disabilities, Dr Tessa Kennedy, a pediatrician and the chair of the AMA Council of Doctors in Training, said.

Some of the “inherent requirements” were perhaps higher than those that typically-functioning medical students and doctors could currently meet, she said.

Helen Craig, the CEO of Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand, said medical schools had made some good progress in promoting diversity, although more work was needed.

Ms Craig responded to concerns around the requirements document by saying: “We hear the concerns and recognise that disability rights is a key issue and also a complex one.

“This is why we put a fairly short timeframe to review the document and hear from those involved on how the guidelines were working out and where they might be improved. As with everything, there could well be areas where they could be better.”

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON

In Australia, the emphasis is very much on producing medical graduates who are tough, resilient all-rounders who are able to do a physically demanding job in any medical specialty.

This hardline attitude is out of step with the US and the UK, where the conversation is much more about encouraging people with disabilities to study medicine and avoiding any whiff of discrimination at every stage in the application process.

The UK’s General Medical Council produced a report in 2008, which stated all entrance tests and interviews must be non-discriminatory, and medical schools should produce advertising material featuring successful medical students with disabilities. The report has an entire chapter on the importance of disabled people in medicine.

Last year, the UK released it’s “Welcomed and valued” report, which stated that, “No health condition or disability by virtue of its diagnosis automatically prohibits an individual from studying or practising medicine.”

Some medical schools in the US have gone even further. The University of Michigan allows students to demonstrate “alternate means” of meeting motor, observational, communication skill requirements.

Last year, the Association of American Medical Colleges released its fourth report on the topic of disability in medical education since 1993, focusing on the day-to-day challenges that medical students with disabilities face.

Dr Lisa Meeks, a psychologist at The University of Michigan, launched a Twitter campaign #DocsWithDisabilities last year that led to a flood of responses from distinguished doctors with disabilities across the US.

Dr Cheri Blauwet, an assistant professor of rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School (and a paralypic champion), shared her story of being mistaken as a patient in a hospital.

“Rather than noticing that I was an early 30-something, confident female with a stethoscope around my neck and a badge reading Dr. Blauwet, my wheelchair was the only thing this man saw,” she said.

“Ultimately, we are striving to normalise the presence of people with disabilities in medicine and debunk what is traditionally called the medical model of disability in which disability is seen merely as a diagnosis, a pathology or an individual flaw,” she said.

EXCEEDING EXPECTATIONS

Only two Australians with quadriplegia have ever graduated medical school in Australia.

Dr Dinesh Palipana, the first junior doctor in Queensland with quadriplegia, suffered a severe spinal cord injury after a car accident in 2010 mid-way through his medical degree, which left him paralysed from the chest down. He was determined to complete his degree at Griffith University and graduated in 2016 with several awards.

He now has a constant stream of patients at the emergency department at Gold Coast University Hospital. He doesn’t intubate or place arterial lines; at a large city centre there are other doctors who can do the hands-on procedural work. Instead, he focuses on conditions such as heart attacks and appendicitis, where patients need to be prescribed medication, sent for a CT scan or require a referral.

“I’m reasonably autonomous within the infrastructure and staffing in a tertiary centre,” Dr Palipana said. “I’ve learned ways to hold my stethoscope and feel someone’s abdomen with the part of my hand that has sensation,” he said.

Dr Palipana’s colleagues and supervisors recognised his contribution by awarding him the Junior Doctor of the Year for 2018.

He has recently faced barriers getting into radiology, the initial specialty of his choice. “A small amount of key radiologists in the decision-making process have been hugely resistant, but there were also some who have been so committed in their support,” he said.

MAKING PROGRESS?

It’s not all bad news. Oddly enough, doctors with disabilities have no trouble getting registered in Australia. The Medical Board of Australia “takes an inclusive and supportive approach to the registration of practitioners with an impairment, providing this can be managed without posing a risk to the public”, says board chair Dr Anne Tonkin.

“As at 31 January, we were monitoring 192 medical practitioners as a result of impairment,” said a spokesperson for AHPRA. “This does not include medical practitioners in New South Wales as cases there are managed by the Medical Council of NSW.”

And many students with less severe, temporary or well-hidden disabilities go on to study medicine in Australia.

Once students with disabilities are safely through the gates of medical school, they actually have access to quite high-quality support services.

The Medical Republic contacted 10 medical schools in Australia to find out the proportion of medical students with disabilities. Seven provided responses.

At James Cook University, 135 medical students out of 1,200 are engaged with accessibility services. Twenty-two of these students have temporary impairments, while 9.4% have ongoing conditions or disabilities.

Professor Tarun Sen Gupta, the director of medical education, said students were encouraged to disclose disabilities or conditions to accessibility services, which then informed the medical school about the adjustments that needed to be made to support that student (thus ensuring confidentiality).

Some of the conditions that might be disclosed by medical students included anxiety, depression and dyslexia.

James Cook University is quite flexible with its medical degree, allowing medical students to take time off or study part-time if necessary.

Out of around 400 students in graduate medicine at The University of Wollongong School, about 35 are registered with disability services. “The most frequent accommodations are provision of a small group environment for examination, occasionally single room,” Dr Alison Tomlin, the head of students at The University of Wollongong School of Medicine, said.

“The reasons behind that can be related to mental health conditions, for example, performance or social anxiety. But it can also be things like musculoskeletal conditions, where they need to be able to get up and move around, or issues relating to late pregnancy.”

The University of Notre Dame Australia has 903 medical students of which 37 have a disability. The kinds of accommodations that are made for these students during exams include extra time, a separate room, only one exam per day, and permission to take food, water or medication into exam rooms.

The University of Sydney currently has 1,057 medical students, and just over 4% have registered with disability services. The adjustments made for these students could relate to exams, alternative formatting of materials, assistive technology, timetabling adjustments and lecture support.

Deakin University and The University of Melbourne medical school were unable to share numbers. However, both medical schools provided general statements about supporting student needs, which mentioned amplified stethoscopes, accessible materials, assistive technologies, access to academic support workers and AUSLAN interpreters, and extended library services as examples.

WHAT WE ARE MISSING

Doctors with disabilities have something that other doctors don’t – they can share a patient’s experience. Their empathic skills are forged in real-life experiences so cannot be taught. Inclusivity is the only way to get those special abilities into the medical workforce.

“I believe it is because of, and not in spite, of my disability that I will make an excellent candidate to become a doctor,” Mather says.

Mather has been forcefully advocating for disability rights for a few years now. She’s collaborated with numerous mainstream newspapers to call attention to the issue. She’s also started a change.org petition calling for a minimum quota of 10 students with disabilities per medical school.

“It has been challenging,” she said.

“Some days, I feel hopeless. Others, I feel hopeful. I received lovely messages from the public and other prospective medical students going through a similar sort of thing that has really touched my heart and motivates me to keep going.

“I also have had a lot of naysayers – but they don’t know me and what I am capable of, so I don’t take it personally.”