The landscape of HIV prevention is changing

The landscape of HIV prevention is changing and with it, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is also evolving.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is a short course HIV antiretroviral treatment (ART) to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition.

Guidelines recommend 28 days of two or three ART agents to be taken within 72 hours of HIV exposure, the sooner the better. Both the exposed individual and the clinician need to be aware of the limited time frame and PEP availability options to ensure timely access to treatment.

Far from being a new concept, HIV PEP has been utilised for over 20 years. Initially, studies of HIV PEP were shown to significantly reduce HIV transmission in occupational exposures and vertical transmission (primarily during delivery), leading to use in risky non-occupational scenarios, where it is called non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis or NPEP.

Although there have been no randomised controlled trials of HIV PEP for non-occupational exposures, many observational trials have resulted in wide acceptance of this approach and the inclusion of PEP as an essential component in the HIV prevention toolbox.

What’s new?

Updated national guidelines for HIV PEP were published in August this year with some notable changes1.

Tenofovir plus either lamivudine or emtricitabine is the recommended two-drug PEP regimen. Where the risk of transmission is higher, the third recommended agent is either dolutegravir, raltegravir or rilpivirine.

PEP should be continued for 28 days following the most recent HIV exposure risk, so if a patient is exposed while already on PEP, the course should be extended to cover 28 days from this point.

HIV PEP is no longer recommended for non-occupational exposures with an HIV positive source who has an undetectable viral load, studies having shown the risk of transmission in this case is extremely small.

Research shows that HIV viral load is a key driver in transmission; so a decrease in viral load will decrease transmission rates. A randomised controlled study of over 1700 serodiscordant couples found that when the HIV positive partner was treated with HIV ART, transmission of infection was decreased by 96%2. This approach is known as treatment as prevention (TasP) where the HIV positive individual takes HIV ART to decrease their HIV viral load and therefore reduce infectivity.

A more recent prospective observational trial of over 1100 HIV serodiscordant couples reported zero within-couple HIV transmission over 1.3 years of followup3. TasP now plays a key role in decreasing transmission globally, both in low and high-resource settings.

In Australia, along with ongoing work to improve HIV awareness and increase access to testing, TasP may encourage earlier testing and hence, earlier diagnosis. Timely engagement into care means recently diagnosed HIV positive patients are starting ART earlier. Coupled with this, improved treatment options have resulted in better virological control, undetectable viral loads and therefore decreased infectivity.

This may eventually have an impact on PEP prescribing rates, however many people presenting for PEP are unaware of the HIV status of the source. Where status is unknown, the probability of the source being HIV positive is estimated by whether they belong to a particular at-risk group, and using local epidemiology.

Assessing the risk

PEP should not generally be prescribed more than 72 hours after exposure. This time frame is often the limiting factor to access, either because the patient did not seek help within the time frame or the clinician was unaware treatment should be expedited.

The 72-hour window acknowledges the theoretical prevention of viral replication and thus dissemination, in the time it may take for the HIV virus to be detected in regional nodes.

Despite this, treatment is advised as soon as possible following exposure. Outside the 72-hour period, PEP may be considered with specialist consultation on a case-by-case basis.

PEP is used for both occupational exposures, such as health care worker needlestick injury, and as HIV prophylaxis for non-occupational exposures (NPEP). The majority of these exposures are sexual, however community needlestick injuries, non-occupational injecting exposures, mucous membrane exposures and blood transfusions may also fall into this category. Different exposures are associated with varying risk, mostly estimated by observational and case based studies, and this will determine eligibility.

Assessing the risk of HIV transmission is dependent upon the risk per exposure as well as the risk of the source person being HIV positive. The NPEP national guideline has made recommendations accordingly. When considering NPEP eligibility for sexual exposure it is important to consider factors which may increase risk, including concomitant sexually transmitted infection (STI), including genital ulcer disease, a breach in the exposed mucous membrane, the presence of ejaculate, and being uncircumcised.

In general, NPEP is recommended in cases of sexual exposure for men who have sex with men where the status of the source person is either unknown or HIV positive with detectable viral load; the higher the viral load, the greater the potential risk.

NPEP for heterosexual exposures should be considered if the source person is HIV positive with a detectable viral load or if the HIV status is unknown. As mentioned above, NPEP is no longer recommended if the HIV positive source has an undetectable viral load.

Where presentation is immediately following exposure, management depends on the type of sexual exposure and patient need. Patients with oral exposure are advised to rinse with water only, avoiding antiseptics and other drying agents. Patients should be instructed not to douche rectum or vagina post sexual exposure. Other skin sites should be washed with soap and water.

Collecting information to assess NPEP eligibility

1. The exposure: time, type and details of the most recent exposure, trauma, first aid response (if any).

2. The exposed person: date and results of the most recent testing for STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis), HIV and other blood borne viruses, allergies, medications including HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), HBV treatment and prior PEP use. A history of any other significant exposures in the preceding three months (or since last negative HIV test) is important to rule out prevalent undiagnosed infection.

3. The source person: HIV status, concomitant STIs or blood borne viruses. If HIV status is unknown, collect risk profile including country of origin and medication including use of PrEP. If HIV status is known, collect treatment history, date and result of the most recent viral load.

PEP eligible patients

Patients need to be aware that PEP is not 100% effective and may be influenced by delayed initiation, poor compliance, further risky exposures and resistant HIV virus. Side-effects and drug interactions may occur depending on the agent prescribed, and some drugs are contraindicated in certain circumstances. For example, tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada) should be avoided in renal disease, and a dose reduction may be required in renal impairment. Common side effects may include diarrhoea, nausea, tiredness, headache and dizziness.

Baseline testing for STIs, HIV and other blood borne viruses should be done prior to treatment to exclude current infection. Liver function tests and electrolytes, urea and creatinine are advised at baseline in case the patient experiences side effects to the PEP regimen. Specialist advice is advised for patients who are hepatitis B or C co-infected as this may influence the appropriate PEP regime prescribed. Similarly, a pregnancy test for women of childbearing age should be performed.

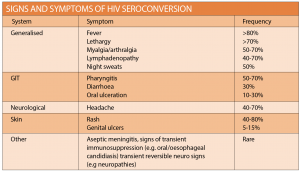

Follow-up and management should be discussed and where appropriate, precautions should be advised, including condom use, avoiding breastfeeding and donating blood. NPEP follow up HIV testing at six months is no longer required, and final evaluation of all screening (BBV, STI and HIV) can be completed at three months. All patients should be counselled regarding the signs and symptoms of HIV seroconversion and instructed to present if concerned (See table at right). If HIV seroconversion is suspected, specialist advice may be required. For full follow-up matrix refer to the national guideline.

Other management issues include assessment of hepatitis risk. Hepatitis A and B vaccination is recommended for all men who have sex with men.

Offer tetanus immunisations to patients presenting with wounds but no history of Tet-Tox.

Counselling and support needs may vary depending on the circumstances, and strategies for future risk reduction, such as condom use and safe injecting practices, are important.

NPEP starter packs containing up to one week of treatment should be available at all emergency departments, although reports suggest smaller regional and community hospitals may not regularly have them in stock.

Where doubt exists, calling the ED will save the patient time. There are PEP hotlines in each state for both patients and clinicians that can help guide determination of eligibility and access.

The frequent flyer

Patients who present regularly for NPEP may benefit from discussion about the circumstances of their repeated exposures. A non-judgmental manner may assist in identifying barriers to safe sex, such as incorrect condom use and inappropriate lubricant use. Other areas of concern such as intoxication or recreational drug use may also have an impact on observation of safe sex practices.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) may be appropriate for some men who have sex with men. PrEP is ART chemoprophylaxis prior to HIV exposure. A combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada), was approved for use for PrEP in adults at high risk in May 2016, however was recently rejected by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee for inclusion on the PBS. PrEP is available via trials in several states or via personal importation. The Australian federation of AIDs organisations has a listing of current PrEP trials at www.afao.or.au.

Patients not eligible

Not everyone who presents after a possible exposure is eligible to receive NPEP. Patients with low and negligible risks may be “worried well” driven by fear of infection. Patients often overestimate HIV risk, and discussion regarding risk-per-exposure data can be reassuring. In cases where the patient insists upon NPEP despite negligible risk, a second opinion may be reassuring for the patient, remaining aware of the 72-hour time limit.

As in all consultations, document risk and exposure history, discussion of estimated transmission risk and guideline recommendations.

Patient reassurance is important, using a supportive approach, ensuring privacy and emphasising patient confidentiality.

Today, with the availability of biomedical HIV prevention options such as PEP, PrEP and TasP, people at risk of sexually acquired HIV no longer have to rely upon condoms alone. Advances in treatment mean people living with HIV have lower pill burdens, fewer side effects and better prognoses.

HIV is increasingly seen as a chronic condition and this is going some way towards changing the public perception of HIV as a death sentence. However, stigma and myth surrounding HIV remains, and the medical community is ideally placed to battle and dispel these for the benefit of our patients and the community at large.

Dr Catriona Ooi is a sexual health physician and clinical lead at the Western Sydney Sexual Health Clinic

Resources:

Information and contacts for patients

AFAO: Australian federation of AIDS organisation

https://www.afao.org.au

http://getpep.info/

Current Australian PrEP trials

AFAO: Australian federation of AIDS organisation

https://www.afao.org.au

https://www.afao.org.au/about-hiv/research/biomedical-prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis#.V9dNiHkcS70

References:

1. ASHM. National guidelines for post-exposure prophylaxis after non-occupational and occupational exposure to HIV (second edition). August 2016 http://www.ashm.org.au/Documents/PEP_GUIDELINES_August2016_FINAL.PDF

2. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493-505

3. Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Sexual Activity Without Condoms and Risk of HIV Transmission in Serodifferent Couples When the HIV-Positive Partner Is Using Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy. JAMA. 2016; 316(2):171-181. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5148.

4. ASHM. HIV, viral hepatitis and STIS- a guide for primary health care. 2014 http://www.ashm.org.au/resources/Pages/1976963411.aspx