While research predicts that pollen levels will soar as global CO2 levels rise, Australia has invested very little in monitoring systems

A growing body of international research is connecting climate change to higher concentrations of allergenic pollen, but the lack of research in Australia has Associate Professor Paul Beggs worried.

In a review published in Public Health Research & Practice this week, Professor Beggs presented research from around the globe linking climate change to an increased risk of allergic reactions.

“Although a large and sophisticated body of research exists … most, if not all, of this is from outside Australia,” he said. “Australian-focused research is, therefore, urgently needed.”

Professor Beggs, an environmental health scientist at Macquarie University who has been studying climate change for 25 years, said many of the weeds that produced pollen allergens were thriving as more CO2 was pumped into the atmosphere.

“CO2 is a driver of climate change, but it also has a huge impact on plants,” he said.

Experimental studies have shown that some plants respond to higher levels of CO2 by boosting pollen production. For example, a US study of timothy grass pollen showed that elevated CO2 increased the amount of grass pollen produced by about 50% per flower.

A study by German researchers revealed that ragweed pollen would likely become more allergenic when exposed to high CO2 levels or drought stress.

“CO2 is a key part of the process of photosynthesis so as the concentration of CO2 changes, it might mean that plants are more efficient,” Professor Beggs said.

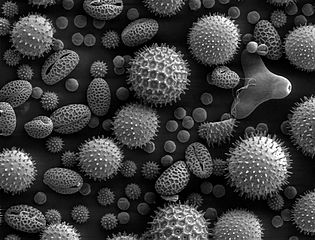

“They can grow bigger or quicker, so there might be more pollen produced. The pollen might be a different size, it might have a different allergen content as well.”

The effects of climate change were “not black and white”, he said, and some plants would suffer while others prospered.

But many of the plants that produced allergens were weeds, so they were likely to be especially good at exploiting harsh and varied environments, he said.

Observational evidence supports the link between climate change and higher pollen levels. For instance, a 30-year environmental study of 23 pollen taxa in Europe showed that the amount of airborne pollen was rising over time.

Another study in central North America showed that the length of the ragweed pollen season had increased by a few weeks since 1995.

The Australian population has a very high rate of pollen allergies, with around a third of adults experiencing allergic rhinitis.

The extent of the public health problem was highlighted in November 2016 when a thunderstorm asthma event occurred in Melbourne, causing 10 deaths and overwhelming the health system, Professor Beggs said.

Despite our high vulnerability to allergens, Australia was not investing as much as Europe or the US in sophisticated pollen monitoring systems, he said.

The Victorian Government has injected $15 million into the world’s first thunderstorm asthma forecasting system, but it only runs pollen monitoring for a three-month period between October and December.

Tasmania and ACT also had reasonable pollen monitoring coverage due to their relatively small size, but it was sparse in other states, Professor Beggs said.

Professor Beggs’ team monitors pollen in two locations in New South Wales, Richmond and Macquarie Park, but the process of collecting pollen and identifying it under a microscope takes several days per week.

In Switzerland, France and Spain, advanced scientific instruments created by companies such as Plair are now being used, that allow highly precise species identification in real time by firing light rays at the pollen and seeing what wavelengths of light reflect back.

Plair’s Rapid-E technology costed about a quarter of a million dollars, but it could save many hours a week of pollen sample processing time, Professor Beggs said.

A few of these real-time pollen monitoring systems scattered across a state might provide enough information about changing pollen levels to allow public health warnings to be issued, he said.

However, Australia had a different climate to Europe, so the technology might need to be adapted for local use, he said.