What to know, and what to do, when you suspect a patient may have the condition.

Unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss is defined as hearing loss of 30 decibels over three consecutive frequencies and over a three-day period.

At times it can be hard for patients to clearly report a hearing loss, with some stating a feeling of “being underwater”, of being unable to converse in crowded rooms or an inability to state the direction of sound.

The condition can occur in any age group, with an age preponderance of 30–60 years, affecting both sexes equally. There are about 4000 new cases in Australia annually.

Most cases (90%) are idiopathic, with no identifiable cause found.

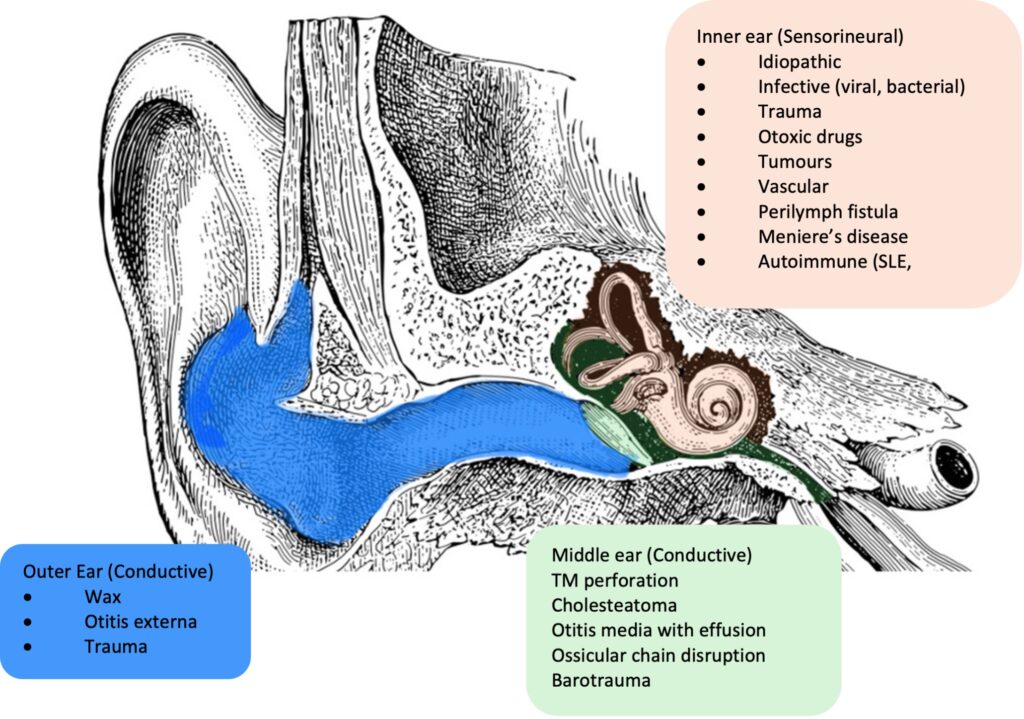

The most common causes of sudden unilateral hearing loss are trauma (including a cochlear fracture), infections (viral), circulatory disturbance and tumours (Figure 1). Early recognition and assessment of sudden hearing loss is key to rapid treatment and improving quality of life.

A thorough history is essential. This needs to include the time course, preceding symptoms or activities, and other symptoms. Previous history of trauma, ear disease and family history may indicate a likely aetiology.

Otoscopy will exclude possible outer-ear causes such as wax or infection. Further, an assessment of the tympanic membrane will help determine if there is any middle-ear fluid or perforation.

A tuning fork assessment can help differentiate a conductive versus sensorineural hearing loss. Cranial nerve examination may also be useful, to detect any red flag signs of conditions such as cerebrovascular events or tumours.

The first-line investigation of sudden unilateral hearing loss is a pure tone audiogram. Additional investigations include MRI with gadolinium and targeted blood tests.

MRI with gadolinium contrast of the internal acoustic meatus and brain is required in cases of asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss (defined as loss of more than 15 decibels in two frequencies) to exclude an intracranial lesion.

Blood tests are not routinely recommended. However, in patients with a history suspicious for autoimmune or inflammatory conditions, serological testing including FBC, ESR, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) levels, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) and anti-phospholipid antibodies may be useful.

The clinical guideline released by the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (2019) provides the following framework for assessing and managing sudden unilateral hearing loss:

- Exclusion of conductive hearing loss.

- Audiogram should be obtained within 14 days of symptom onset.

- An MRI should be obtained to exclude a cerebellopontine angle tumour.

- Systemic steroids (1mg/kg/day prednisone 14 days) should be started within two weeks and no later than six weeks from the onset of symptoms if no contraindications exist.

- Intratympanic steroids are recommended for those patients who do not improve with systemic steroids. This is generally done through repeated injections through the tympanic membrane within six weeks of symptom onset.

- Follow-up audiogram after treatment completion and six months after symptom-onset to ensure resolution

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be offered within one month of hearing loss in patients who fail initial management

- The following are NOT recommended in the management of sudden unilateral heating loss: routine blood tests, CT scans of the head, medications such as thrombolytics, vasodilators or vasoactive medications.

In certain cases (35-40%) of unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss, hearing may not recover despite treatment. After six weeks, in the absence of any specific cause being found, management goals shift to improving quality of life.

Preservation of normal hearing on the contralateral side is key through the reduction of noise exposure, precautions when exposed to loud noise and caution with ototoxic medications.

The unilateral loss of hearing creates impairment of directional hearing and discrimination of sound.1 Hearing aids and implants may be useful in improving these deficits.

The main non-surgical treatment for irreversible unilateral hearing loss is a CROS (contralateral routing of signal) hearing aid.

A CROS aid has two components: a microphone and the hearing aid. Sound is transmitted from the side of the deaf ear through the microphone to the normal-hearing ear through a hearing aid. This is the aid recommended for people with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss but normal hearing in the unaffected ear.

In patients with a contralateral hearing loss, a BiCROS aid can be worn, where the better hearing side is additionally amplified into the hearing aid.

Surgical treatments for unilateral sensorineural hearing loss include bone conduction implants and cochlear implants.

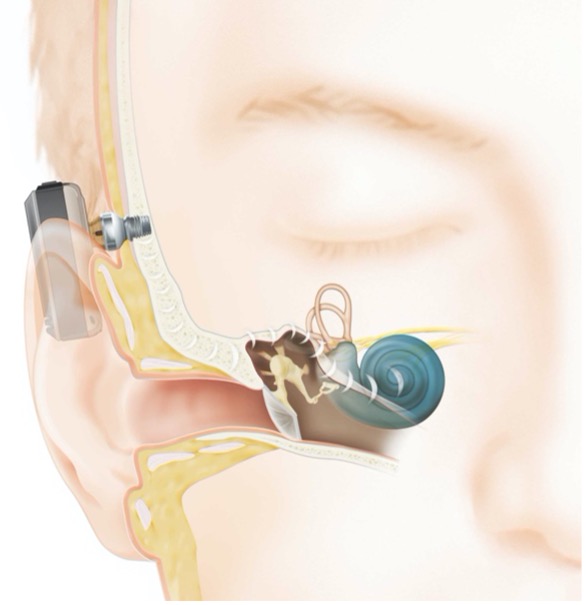

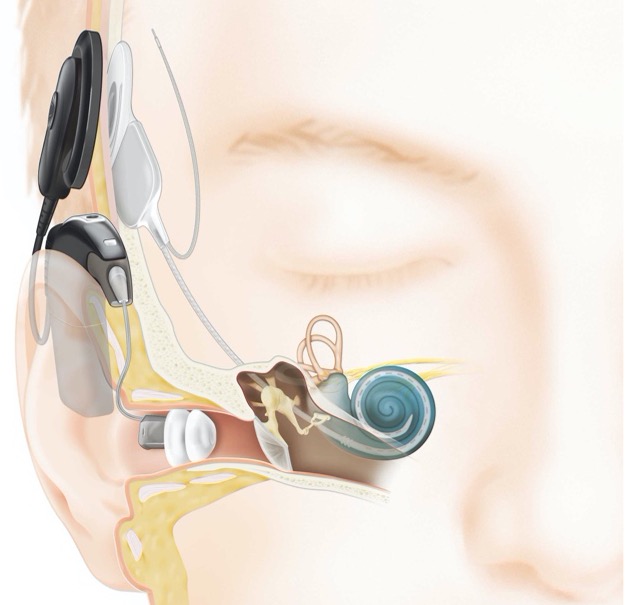

Bone conduction implant devices work through the reception of auditory signals, which are converted to vibrations through the skull that are then transmitted to the contralateral cochlear.

Bone-anchored hearing implants have a receiver/transducer and an implant. These implants integrate with the bone, to allow for vibration and transmission of auditory signals.

Implants can be percutaneous or transcutaneous. Percutaneous implants have an abutment that protrudes from the skin, making direct contact with the receiver/transducer (Figure 2), while transcutaneous implants have an indirect connection with no abutment protruding from the skin, and rely on magnetic attraction under the skin (Figure 3).

Meta-analyses studies have demonstrated some benefit of bone-anchored hearing aids over CROS systems, but the evidence is of low quality and limited.2

Recently, unilateral sensorineural hearing loss is considered a criterion for cochlear implantation in adults. Cochlear implants are surgical devices implanted under the skin with electrodes passing into the cochlear.3 They work by receiving and transmitting audiometric signals through electrodes to the efferent nerve fibres of the cochlear (Figure 4).

Evidence suggests the benefits of cochlear implants include partial reconstitution of binaural hearing that does not interfere with the unaffected normal ear and does not affect baseline speech understanding.4

Summary

Unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss requires urgent assessment. Early initiation of steroids, obtaining an audiogram and referral to an ENT surgeon allow for improved outcomes.

An MRI of the internal auditory meatus and brain is the recommended imaging for all cases of asymmetrical hearing loss.

In cases where the hearing loss persists despite treatment, audiological rehabilitation should be considered. Options include the traditional CROS or BiCROS hearing aid, a bone-anchored hearing aid or a cochlear implant.

Sudden hearing loss in primary care

- Exclude causes of conductive hearing loss; e.g., wax, perforation, infection

- Organise urgent audiogram to confirm sensorineural hearing loss

- Initiate oral steroids (1mg/kg) if no contraindications

- Urgent referral to otolaryngologist for consideration of MRI, intratympanic steroids and hyperbaric therapy.

References

1. Cherry, E.C., Some Experiments on the Recognition of Speech, with One and with Two Ears. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 1953. 25(975).

2. Baguley, D.M., V. Plydoropulou, and A.T. Prevost, Bone anchored hearing aids for single-sided deafness. Clin Otolaryngol, 2009. 34(2): p. 176-7.

3. Buchman, C.A., et al., Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2020.

4. Vlastarakos, P.V., et al., Cochlear implantation for single-sided deafness: the outcomes. An evidence-based approach. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2014. 271(8): p. 2119-26.