Nordic countries know something we don’t about using public-health data for research

I’d just crumpled onto the couch at home when an unknown number flashed up on my mobile. “It’s Christian Nøhr calling from Denmark,” said a warm voice down the line. I did the awkward phone-to-shoulder contortion as I scrambled for a pen, notepad and dictaphone.

I wasn’t expecting this call.

My half-hour chat with Professor Nøhr, a health informatics expert from Denmark’s Aalborg University, opened a small window into what I’ve decided to call “data heaven”.

Until very recently, Australian researchers have had to beg federal, state and territory governments for linked health data and could wait years to gain access.

In one instance, cited by the Productivity Commission in its March 2017 report, there was a five-year delay in the supply of vital data that went on to show an increased cancer risk for young people undergoing CT scans.

“Had [the] study been approved sooner, and been able to proceed at an earlier date… we would have had results sooner, with potential benefits in terms of improved guidelines for CT usage, lesser exposures and fewer cancers,” one researcher said.

Contrast this to the Danish system, where GPs, specialists, pharmacists and hospitals all interact using a central database, which has been in place since 2010. Each patient’s journey through the system can be tracked in detail using a unique ID number, and there is a clearly defined process through which researchers can seek ethics approval and access de-identified data.

Denmark’s primary care portal, Sundhed.dk, allows 98% of GPs to communicate directly with other healthcare professionals. Patients cannot receive treatment outside the system and are unable to edit their medical information. But they do have the ability to tag specific medicines as “private”, which means doctors can be fined for not seeking consent prior to accessing the information (unless it’s an emergency situation).

The most remarkable aspect of the Danish system – and the most alien from an Australian perspective – is the broadbased acceptance of data collection and monitoring by government. “We expect the public system to take good care of our data”, said Professor Nøhr. By comparison, lack of trust in data sharing arrangements is “choking” the use of health data in Australia, according to the Productivity Commission.

This is unfortunate because linked, de-identified medical records are the Holy Grail for health researchers. Retrospective analysis of millions of anonymised data points can reveal a whole galaxy of patterns, without the expense and hassle of a clinical trial.

Once granted access to government-held medical data, researchers can view real-life information about the long-term outcomes of patients taking particular medications. And linking that information to social variables can yield an even richer understanding about how the health of individuals is affected by education, employment, housing, or income. The health system can be made vastly more efficient using the insights from data analytics.

But while other countries are increasingly using health data in clever ways, Australia is being left behind. “This is a global phenomenon and Australia, to its detriment, is not yet participating,” the commission’s report said.

So what are Scandinavia’s secrets to safely unleashing the power of health data, and what’s stopping Australia from doing the same?

ID numbers

To find out, I emailed peak bodies for health research in Norway and Sweden and asked them to spill the beans. Both of these countries were listed as top nations for health data sharing and linkage by the OECD’s 2015 report, along with Denmark, Finland, Canada, Czech Republic, Israel, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK.

Birgitta Lindelius, a spokesperson for the National Board of Health and Welfare in Stockholm, Sweden, said: “One reason is probably our long tradition when it comes to registers and the personal identity number (PIN) that is an important part of the registers. The PIN gives us the possibility to link data.”

Statistics of diseases and surgical treatment of patients have been published for more than 100 years in Sweden, regulated by the Act for Health Data Registers. County councils are, by law, obliged to send information on the care given to the National Board of Health and Welfare.

Data are disclosed for research purposes up to 400 times every year by means of an exception in the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act. “We believe there is a big trust among both researchers and citizens in general in this system,” said Ms Lindelius.

Norway has a similar tale. Using the 11-digit ID number given to all citizens, data from different registries can be linked together. “This provides valuable knowledge about the occurrence of disease, the use of healthcare services and results from public health measures,” Marta Ebbing, the director of Health Registries at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, said.

Denmark introduced its central person register number in 1968. This ID is used for everything in relation to national and local government, including healthcare, drivers’ licences, bank accounts, public education and employment. “It gives a unique opportunity to do research, especially within epidemiology where you can actually trace many, many different bits of information about the individual from birth to death,” said Professor Nøhr.

In fact, all OECD countries with a strong health data linkage use a single number to identify individuals and link data sets together. New Zealand has a national health index number, South Korea has a resident registration number, Israel has an ID number and the UK has an NHS number.

By comparison, there was a furore over the Hawke government’s proposed Australia card in the 1980s. Even today, Australian health data can’t be linked using the Medicare number because people can have multiple cards (or multiple people can have the same Medicare number). Instead, researchers use statistical techniques to piece together health data sets in Australia as best they can.

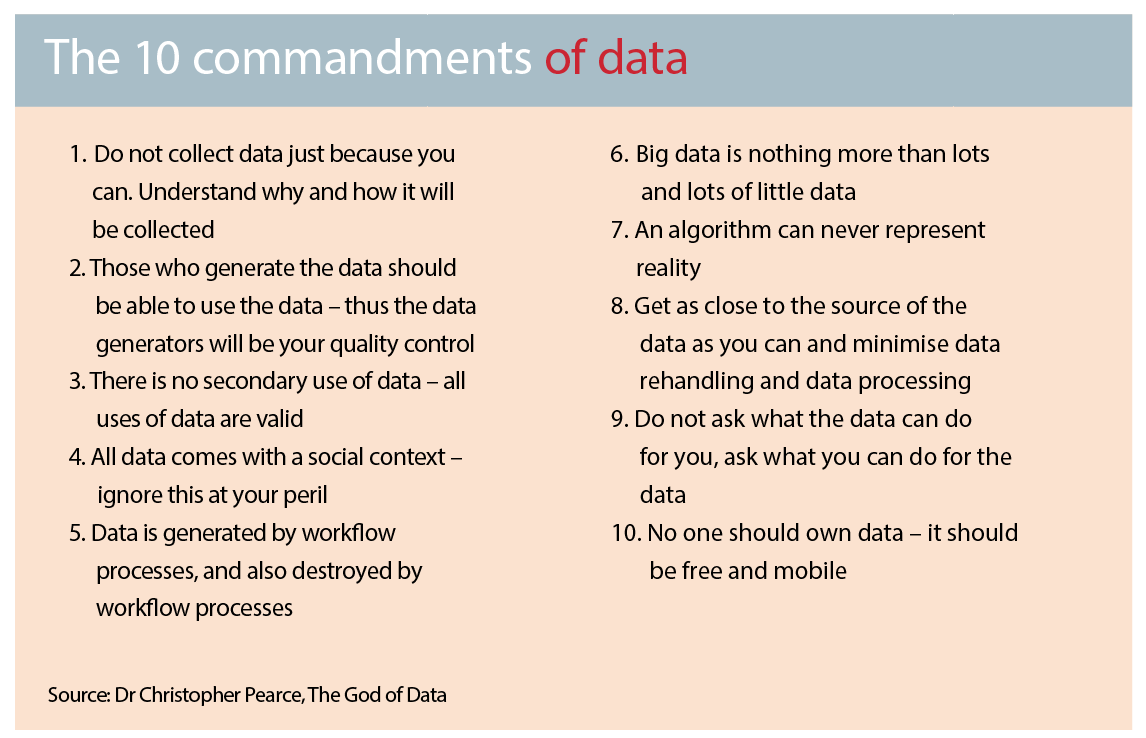

“Researchers might take the first three letters of your first name and surname, your date of birth and something else and then creating a hash key out of it and that then becomes unique to you,” Dr Christopher Pearce, the vice-president of the Australasian College of Health Informatics, said.

The answer is ‘no’

There are legal restrictions against the routine linkage of health data in Australia. For instance, the National Health Act 1953 prevents the unauthorised linkage of MBS and PBS data. But the black letter of the law wasn’t the greatest barrier that researchers faced when it came to linking health data, Barry Sandison, the director of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), said.

The biggest problem was institutional resistance to change. “People just assume because something has always been done a certain way, that’s right,” said Mr Sandison. Even when there were no legal restrictions, institutions would respond to a request for data by the AIHW with: “the answer is ‘no’ unless you really can prove otherwise”, he said.

There was a very real culture of aversion and risk avoidance in the public sector when it came to data release, the Productivity Commission said.

“Too often public-sector data custodians and researchers are required to negotiate multiple pieces of legislation, many with criminal offences that apply strict liability for various actions,” the report said. “It forms a complex web, with intimidating consequences for missteps, that reduces the likelihood that data would be put to good use.”

This was a major factor accounting for variability across countries in health data availability, Jillian Oderkirk, a senior analyst at OECD based in Paris, told The Medical Republic. “The, maturity and use [of health data] can be attributed to concerns about, and uncertainty about how to protect, patients’ rights to privacy,” she said.

The big worry was that identifiable health data would be released inappropriately, causing harm to patients, such as reputational damage or embarrassment, discrimination, identity fraud, or commercial harm. These risks – and the desire for privacy and confidentiality – should not be downplayed or trivialised, the commission report said.

In another respect, health data suffered from a “tragedy of the commons”, as no one institute benefited from volunteering information, said Nicholas Gruen, the CEO of public policy consulting firm Lateral Economics.

Data sharing was also not adequately resourced, said Professor Sallie-Anne Pearson, the head of the Medicines Policy Research Unit at the Centre for Big Data Research in Health.

“One of the greatest challenges has been that many of the people tasked with getting the data to researchers have had to do this on top of their primary role,” she said. “It is all around goodwill and doing favours for people rather than necessarily saying, ‘this is my job and one of my KPIs is to ensure that the data flows’.”

The other important contributing factor is the public’s attitude towards data sharing. It’s no overstatement to say that Scandinavian countries, with their social-democratic traditions, high taxes, multi-party coalition governments, and impressive health systems, have a more trusting political climate than in Australia.

There is some evidence to suggest Australians aren’t necessarily ideologically opposed to governments using data sensibly. A recent survey by Research Australia showed more than 90% of Australians were willing to share their de-identified health data to advance medical research and improve patient care.

But it is easier to obtain a social licence for government surveillance when it goes both ways. And Scandinavia had a long history of public service transparency, Professor Arne Björnberg, the author of the Euro Health Consumer Index, said.

In Sweden, for example, all official government documents are freely available – to the point where any citizen can walk into the prime minister’s office and ask to see non-confidential memos that were sent the previous day.

The big divide

Most of the top countries for health-data linking have small populations. Scandinavian countries have around five to 10 million people, New Zealand has around five million and Israel has roughly 8.5 million. On that list, only the UK, Canada and South Korea stand out as countries with larger populations.

Being small definitely helps with organisation, but the central driver of health-data linkage is the fact that most of the key databases are contained within one jurisdiction – something that does not occur in Australia. Our federated model means health is split between the Commonwealth and state and territory governments.

“So the PBS and MBS data, for example, are national,” said Professor Pearson. However, hospital data and many disease registries, like cancer notifications, are under the custodianship the individual states.

“What we have is this classic example of a wealth of information generated but it sits in lots of different silos,” she said. “It is a very, very challenging pathway to navigate to understand even where the data is held, who is the custodian of the data, who can approve release of the data and even more complex if you want to bring those data sets together.”

The importance of control by one jurisdiction is underscored by the fact that Australian states have been conducting fruitful research with their own health data for many years.

“NSW Health, for example, holds many, many datasets and it links them regularly for research,” Professor Pearson said.

The Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) has been bringing data together for the purposes of research for over a decade, Professor Pearson, who chaired CHeReL’s ethics committee for many years, said.

That’s not to say that federal and state health data are never linked in Australia. There are a number of institutions – including six state units, the AIHW, and the Centre for Data Linkage – that regularly combine hospital, emergency department and disease registry data.

In 2012, a new accreditation was brought in to further support the linkage of health data. There are currently three accredited Integrating Authorities: AIHW, Australian Bureau of Statistics, and the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

The Commonwealth government also threw open the doors to its data vaults, launching the data.gov.au website in August last year.

Through this initiative, a billion lines of linked MBS and PBS data were made available online, protected through encryption and de-identification.

But two cryptographers at the University of Melbourne successfully re-identified some of the service providers, and the government quickly removed the data set.

Humanising data

Health researchers welcomed the sentiment behind the release of MBS and PBS data, but criticised the execution, the timing and the usefulness of the dataset itself.

PBS and MBS entries were actually very coarse data, Dr Pearce said.

They were collected for administrative purposes, not for clinical purposes.

Electronic medical records were the ultimate source of health data, he argued. And, in the absence of a fully functioning My Health Record, Australian researchers were leap-frogging the government entirely and forming partnerships with GP practices and hospitals to gain access to this information directly.

Dr Pearce is the research director of one such enterprise, Outcome Health, which provides data analytics services for Primary Health Networks in return for access to medical data for research purposes. “So MBS data says there was an item on this date; I can tell you what the consultation was, how long it was, what the diagnosis was, what the prescription was on that day,” he said. “The last thing we want is MBS data.”

An estimated $2 billion has been poured into My Health Record but uptake by GPs has been so low that some GPs argue the system needs to be shut down and rebooted. The government remains hopeful, however, announcing in June last year that it was engaging HealthConsult to help develop a framework for the secondary use of that data by researchers.

Many countries had already taken this step, said Ms Oderkirk from the OECD. “Data is already extracted from national EHR systems for national research and statistics in Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Singapore, Iceland, Sweden and UK,” she said.

Primary-care problems

The sharing of primary-care data by governments has proved explosive in more than one instance, however. The UK’s controversial care.data program to store all data about GP consultations on a single database collapsed amid privacy concerns last year. Denmark also ran into trouble with its Danish General Practice Database, a research initiative using primary care data. The system was rolled out in 2007 to capture data on medicine, treatment, diagnoses, referrals, discharge summaries and lab work in relation to diabetes.

By 2013, all GPs were required to install software (Sentinel Datafangst), which automatically sent information to a central database.

Concerns were raised over the amount of information being sent off to the database and, in 2014, two GPs reported the database to the police for misuse of data. After intense public debate, the database was closed down and a court ordered all the data, about 40 million entries, be deleted.

Why is primary care data such a dangerous material? It’s the highly personal nature of the data, according to Dr Pearce.

“People try to treat data as if there is no social context and it is just a dot,” he said. But GP patient records are sensitive and difficult to de-identify.

“For instance, GPs will write in the diagnosis field information that make the data identifiable. So they don’t write high blood pressure, they write ‘Mrs Smith brought me some flowers today’. It’s very cute. I love it. But unless you spend a lot of time and get a lot of things in place, it is very easy for this to blow up in your face.”

In his business, Outcome Health, Dr Pearce engages with GP practices over a long period to work through these issues.

GPs will be incentivised to provide high quality, clean data if they receive insights based on that data, so Outcome Health finds a way to translate data into useful information for GPs.

The process of gaining trust in the private sector was gradual, whereas “governments tend to be blunt instruments”, said Dr Pearce. “If the government was to run a program to extract primary care data, what would they do? They’d build an extraction tool, suck it into a big vat and then look at it because that’s what they are used to.” And that’s when privacy alarms start going off. “That’s why there was a kerfuffle with the PBS and MBS data,” he said.

Changing tack

Many public-policy conversations can essentially be reduced to the aphorism, “let’s just be more like Sweden”.

Fortunately, more thought has been invested in the question of how Australia can replicate other countries’ culture of data utilisation. The Productivity Commission’s Data Availability and Use report lays out a detailed framework and a specific timeline.

It recommends that new legislation, the Data Sharing and Release Act, be passed before 2018. This would establish a “presumption of open data”, where all non-sensitive data would be made available as a matter of course.

A public official, the National Data Guardian, would oversee the release of data and Accredited Release Authorities, such as the AIHW and public-sector agencies, would give data to trusted users. Predictable funding would be allocated for updating “national interest datasets”.

“What is already being done overseas is indicative of what is possible,” the Productivity Commission said. “There is enormous untapped potential in Australia’s data.”