Palliative care is harder to deliver to rural residents, and disasters always threaten to cut them off entirely.

Two weeks before Easter 2017, Cyclone Debbie hit southeast Queensland, bringing record floods to the Logan region just south of Brisbane.

My aunt, uncle and cousins lived on a horse property in the area, caring for my grandmother, Rosie, who had advanced breast cancer and early-onset dementia.

Just a half-hour down the freeway from Brisbane, Logan isn’t remote by any stretch of the imagination; but it isn’t all suburban either, and the neighbourhood where my family lived consisted mostly of small farms.

When the floodwaters started rising, the street which they lived on was completely cut off – my aunt and cousins ended up unable to get back home, and my uncle was left caring for Rosie, whose condition was starting to deteriorate.

When nan took a turn for the worse, my uncle called in the local community palliative care service, who had been liaising with the family for quite some time.

But the team were unable to safely get through the floodwaters surrounding the property and she was without palliative care for several days.

Eventually the road was cleared, the palliative care team was able to get through and she died comfortably at home two weeks later.

But the last two weeks of my nan’s life could have gone very differently, and for many other families living in the regions, things frequently do go differently.

Rural Doctors Association of Australia president Dr John Hall says logistics such as transporting hospital beds and equipment makes it exponentially harder for rural Australians to access community-based palliative care.

“The consumables are often coming from a public hospital – sometimes that’s the local public hospital or sometimes it might be a regional palliative care unit a couple of hours away from that community,” he tells The Medical Republic during National Palliative Care Week.

“There are some areas where you have outreach teams from large regional hospitals that will come out and help to set up palliative care.

“But with the tyranny of distance and issues with access that can be variable across the country.”

Compounding this issue is the increased need for home palliative care in rural areas, where family members would have to travel longer distances, and possibly leave working farms, to visit relatives receiving end-of-life-care at a hospital.

Although there is no data differentiating between rural and metro palliative care preference, a Grattan Institute report found that up to 70% of Australians would prefer to die at home – but recent data from the Australian Institute for Health and Wellness found that just 10% of palliative care services are delivered in-home.

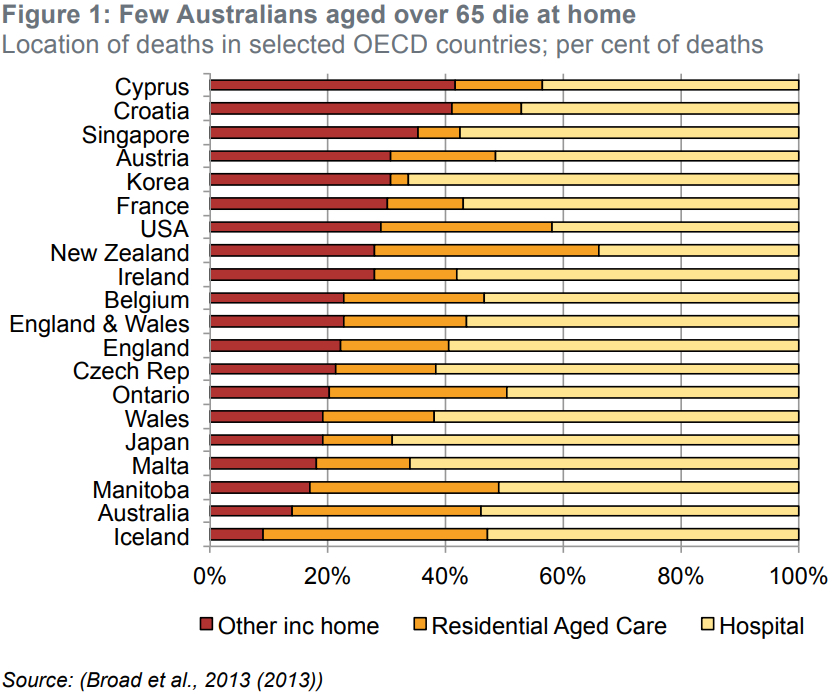

Moreover, Australia lags behind other OECD countries in terms of at-home deaths.

“People overwhelmingly want to die as close to home as possible, but because it’s harder to access home-care services in rural areas – remembering many rural towns don’t have domiciliary or community nursing and rely on nurses visiting from a private GP practice or from the community health department at the nearest hospital – inevitably, if there isn’t the capacity to provide community care, or in-home care in a rural community, many of those patients will actually palliate in a hospital facility in a rural town,” Dr Hall says.

According to Dr Hall, rural GPs and nurses are already doing the “heavy lifting” in palliative care in the regions but could operate more efficiently if there were fewer jurisdictional differences in funding and services.

“Most rural GPs learn palliative care as part of their core training, and there’s absolutely no reason why we couldn’t work on making sure that more of those doctors have those skills and that the nursing teams around them are equally upskilled,” he tells TMR.

“It’s an area where you certainly can provide upskilling, and there’s a lot of palliative care that today is being delivered by rural GPs in rural hospitals, in part because of the difficulty accessing specialty services [at home].”

National Palliative Care Week runs until 29 May, aiming to raise awareness about the multiple benefits of quality palliative care.