An understanding of what constitutes safe and unsafe perforations allows clinicians to appropriately triage the concerning pathology.

Tympanic membrane perforations are seen frequently in general practice.

Some perforations can be associated with significant disease, such as cholesteatoma which may cause major morbidity.

DEFINITIONS AND NATURAL HISTORY

Tympanic membrane perforations are holes in the ear drum that most commonly occur as a consequence of either ear infections, chronic eustachian tube dysfunction or trauma to the ear.

Acute middle ear infection (acute otitis media) is a common condition occurring at least once in 80% of children. Most acute otitis media resolves with spontaneous discharge of infected secretions through the eustachian tube into the nasopharynx.

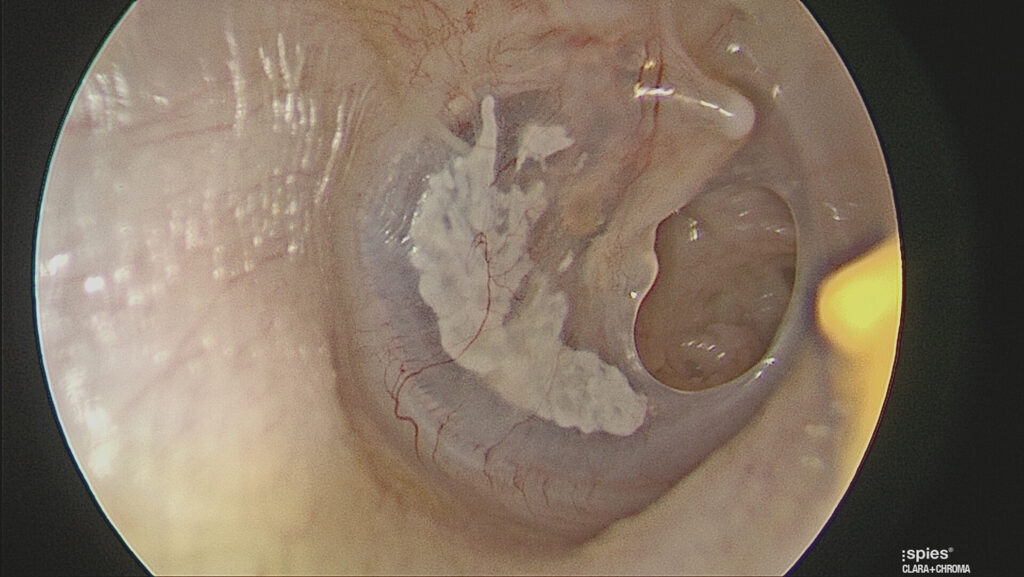

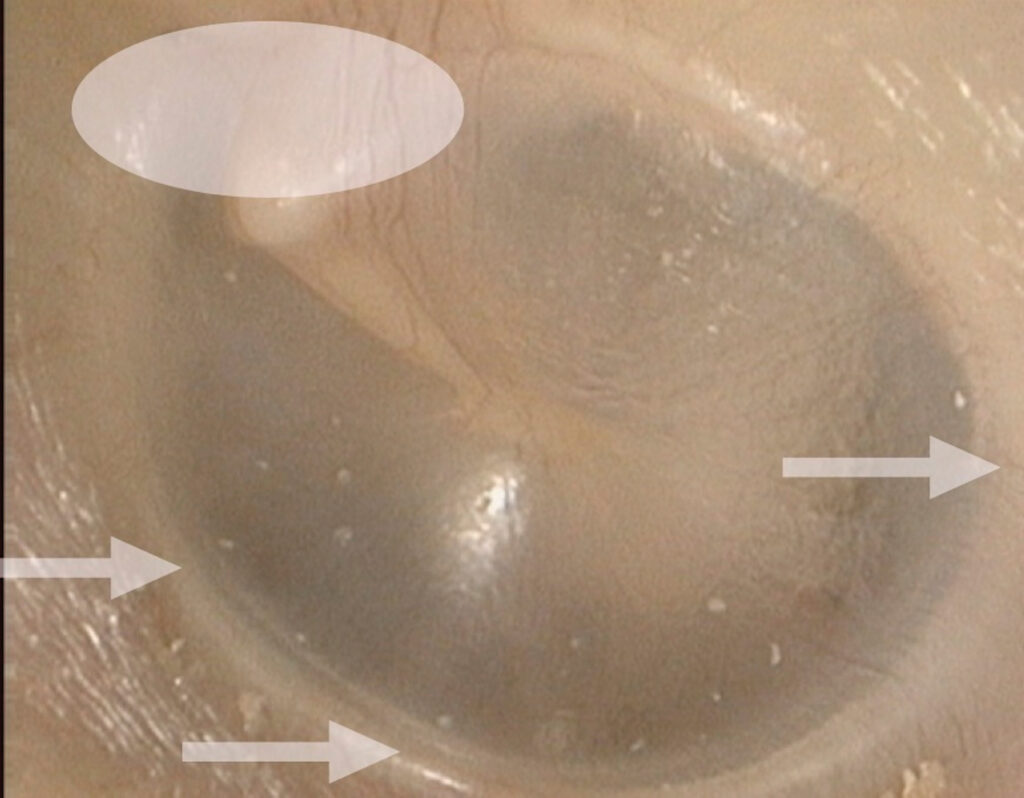

Occasionally when the infections are frequent, there is extensive scarring (tympanosclerosis and myringosclerosis) of the ear drum and middle ear . This scarring compromises blood supply to the healing ear drum and occasionally stops the hole from healing. (Figure 1)

Traumatically induced holes occur from a rapid compression of the air column in the external ear canal, most commonly from a blow to the side of the head. (Figure 2) In the Australian population this occurs most frequently either with water skiing and surfing accidents.

Cholesteatoma is an epidermal inclusion cyst within the middle ear, temporal or tympanic bone with a propensity for expansion, recurrent infection and destruction of surrounding structures. This condition typically presents as a perforation in the attic or margins of the ear drum.

The condition has an incidence of approximately one in 10,000 in adults and one in 30,000 in children.

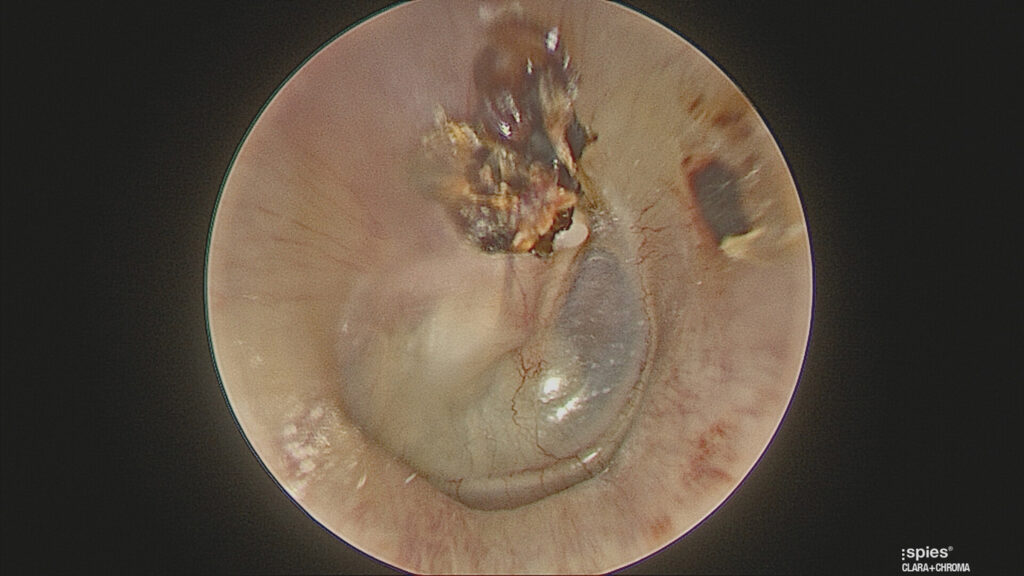

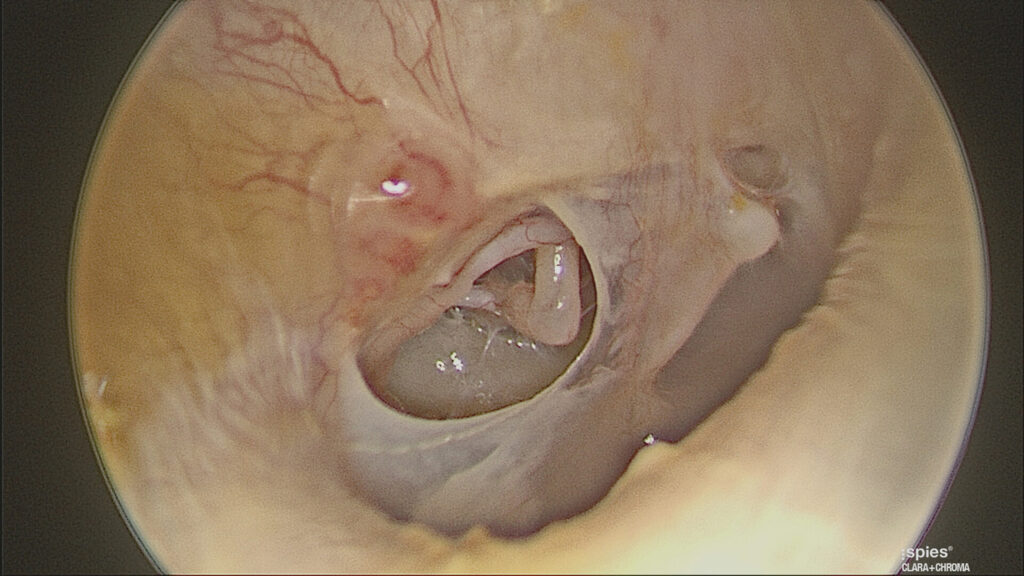

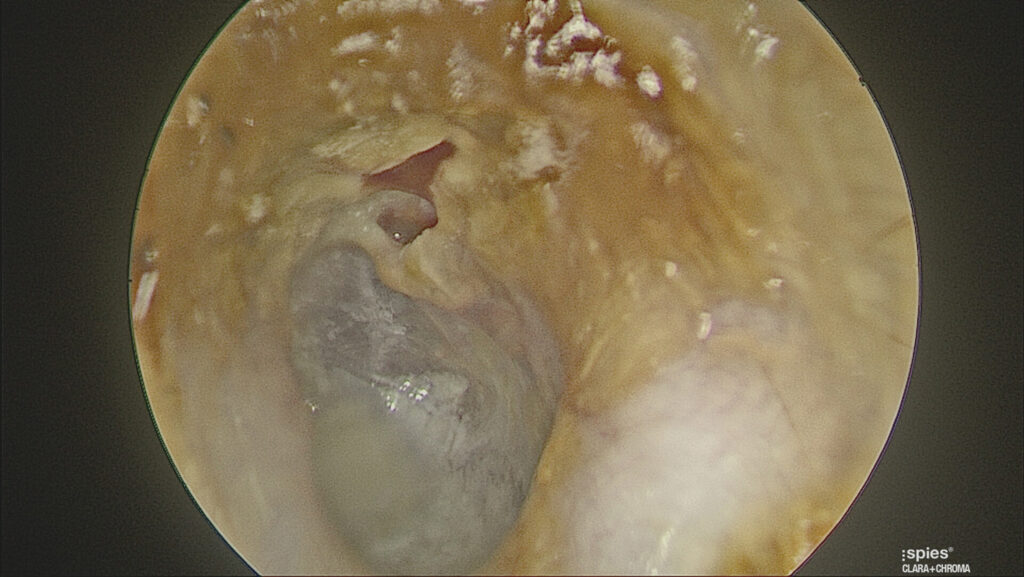

The vast majority of cholesteatoma is acquired and is thought to evolve when negative pressure in the middle ear space, from long-term eustachian tube dysfunction, causes development of a collapsed eardrum known as a “retraction pocket “in the tympanic membrane. Accumulation of debris within the retraction pocket leads to gradual expansion and recurrent infection. (Figure 3)

DIAGNOSIS

Examination of the ear is divided into anatomical (otoscopic/microscopic inspection) and physiological (clinical hearing and balance testing) assessment.

A tympanic membrane perforation (hole in the ear drum) is diagnosed when a deficiency in the ear drum is noted. When diagnosing a hole in the ear drum two common misdiagnoses are made; calling either a thin or retracted tympanic membrane a perforation.

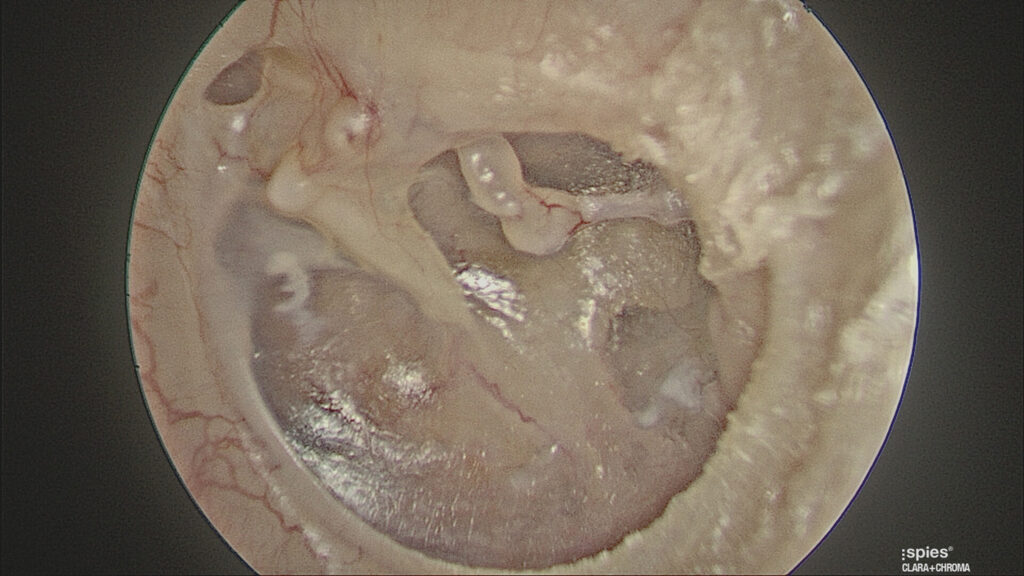

Thin ear drums (dimeric segments) occur with spontaneous closure of the perforation where the healed segment lacks the fibrous (structural) layer. This creates a part of the ear drum where it is often easier to see middle ear structures and therefore it appears like a hole in the ear drum. (Figure 4). Pneumatic otoscopy, moving the ear drum with a sealed speculum, easily differentiates a thin ear drum from a hole in the ear drum (which will not move with insufflation).

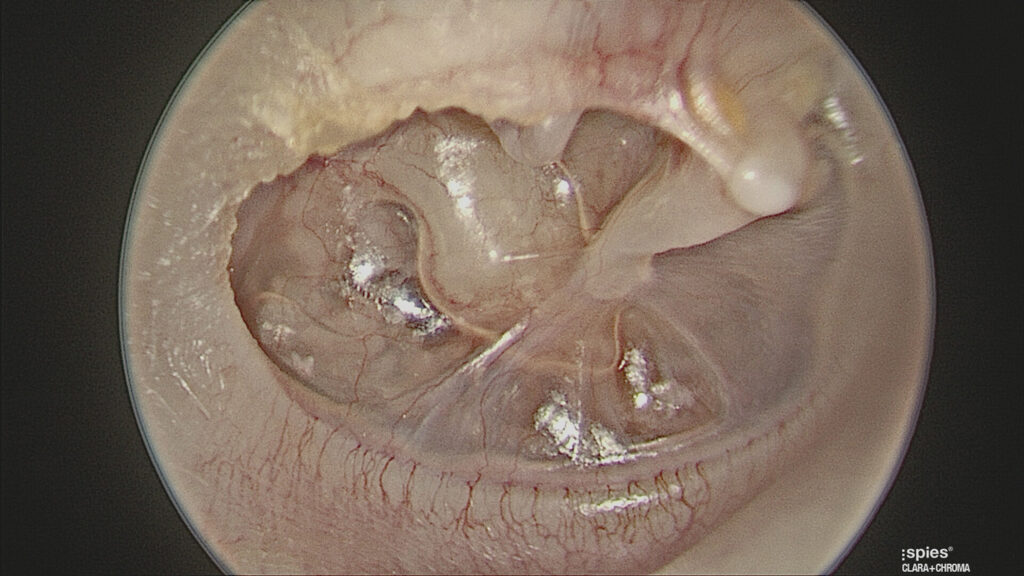

Retracted ear drums occur due to persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction. The healing ear drum collapses onto the structures of the middle ear. The thin retracted ear drum draped over the medial wall of the ear outlines middle ear structures, again making it easy to mistake this for a hole. (Figure 5)

A diagnosis of cholesteatoma is made based on history-taking, endoscopic/ microscopic examination of the ear, audiometry and CT imaging. Many patients will remain asymptomatic for a significant period of time.

Other patients will be symptomatic due to expansion of the mass with pain, repeated infection or destruction of adjacent structures manifesting as a conductive hearing loss, vertigo or facial nerve palsy. Examination findings are variable but typically show a defect in the superior (pars flaccida) portion of the tympanic membrane, with keratin debris in its centre. (Figure 3)

TYMPANIC MEMBRANE ANATOMY

The pars flaccida region of the tympanic membrane is that region above the short process of the malleus. (Figure 6) Typically this area is called the attic region and is clean and smooth with a few blood vessels noted. If this region is not smooth and free of wax/debris and in particular if a perforation can be seen in the attic, then a cholesteatoma may be suspected.

The annulus of the ear drum delineates the margin. A marginal perforation is a sign of an unsafe ear.

MARGINAL AND ATTIC PERFORATIONS (THE UNSAFE EAR)

When either a marginal or attic perforation is seen, this is an unsafe situation. A marginal perforation is one where the hole reaches the annulus of the ear drum. (Figure 7) An attic perforation is a hole above the short process of the malleus. (Figure 8) Both of these may be a sign of cholesteatoma which often requires surgical intervention.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Dry central safe perforations – away from the attic or the annulus margins. Generally will not progress to serious pathology.

Unsafe perforations – Attic, marginal and chronically discharging perforations. May progress to serious pathology.

TESTS BEFORE REFERRAL

- Audiogram

- CT scan of the temporal bone if cholesteatoma suspected

- MRI is sometimes ordered by the ENT Surgeon if there is sensorineural hearing loss or suspicion of intracranial disease.

MANAGEMENT

Most acute perforations from infection will spontaneously heal with culture directed antibiotic treatment. If the middle ear is soiled then topical antibiotics (such as ciprofloxacin) are used for a week.

The patient should maintain strict water precautions and be regularly checked until the hole heals, usually in a few weeks. Occasionally the acute perforations will not heal and once the perforation exists for more than three months it is defined as chronic and may require referral for surgery.

Dry safe chronic perforations are only managed surgically if the patient is symptomatic. The patient will be usually be complaining of either discharge or hearing loss. In this case some form of tympanoplasty (repair of the ear drum and/ or ear bones) is required. Modern methods now allow most of ear drum repairs to be performed through the ear canal with no incisions around the ear. Unsafe perforations are generally managed surgically to treat the underlying cholesteatoma and prevent complications. Three surgical techniques are offered for cholesteatoma depending on the disease spread and surgeon specific factors:

- Transcanal (through the ear) surgery with microscope and endoscope to clear the disease if it has not spread to the mastoid bone. With the emergence of high definition and 4K endoscopy in the last eight years this technique can manage to treat most middle ear and attic disease.

- Intact canal wall mastoidectomy/ tticotomy) if the disease has spread to the mastoid. This method maintains the ear canal wall but may require a second surgery and regular surveillance scanning for a few years.

- Canal wall down (modified radical) mastoidectomy where the ear canal wall is removed. This method is now largely only used for severe disease where the canal wall is already damaged or disease extends deep into the temporal bone. With this method the patient may ultimately require regular cleaning of the ear on a six to 12 monthly basis in the surgeon’s office. Furthermore, the hearing results are generally not as favourable as the two conservative methods and hearing aids are difficult to fit after the operation.

The main purpose in all methods is to remove the disease and create a safe, dry ear. A secondary benefit may be restoration of hearing.

FOLLOW UP

Once cholesteatoma surgery is performed the surgeon will usually review the patient yearly, often with MRI scanning for a few years to ensure there is no recurrence.

The potential for recurrent cholesteatoma is present for many years as the underlying eustachian tube dysfunction may still persist. Therefore, any patient with repeated pain, infection or worsening hearing loss, even many years after the surgery, should be sent back to the surgeon for re-evaluation.

WHEN TO REFER

- Attic or marginal perforation (especially if patient is symptomatic)

- Central perforation that is symptomatic (discharge or hearing loss)

- Painful, discharging ear where the attic can’t be clearly visualised

- Chronically discharging or bleeding ear

- Perforation with significant clinical hearing loss

- Cranial nerve deficits

- Deep earache or headache with perforation

Associate Professor Nirmal Patel is a Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery at the University of Sydney and Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. He is the Founder and Director of Kolling Deafness Centre, University of Sydney and general secretary to the International Working Group of Endoscopic Ear Surgery