These conditions have not traditionally been recognised as a problem in rural and remote areas.

First Nations Australians present to ED with asthma and allergic disease twice as often as Australians of other descent.

Australia, commonly referred to as the allergy capital of the world, is not exempt from the racial and ethnic disparities in disease burden seen on an international scale. But unlike other countries, there is little research into whether such disparities exist in Australia on a socioeconomic level.

To address this gap, researchers from the University of Queensland have undertaken a retrospective analysis on ED admission data from the Sunshine State to explore the incidence rate and trends of asthma and allergic disease presentations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Their findings, published in BMJ Open, reveal Indigenous Australians have a higher rate of asthma and allergic disease-related ED presentations compared to non-Indigenous Australians across regional rural and remote areas.

Dr Melanie Wong, a paediatric allergist and clinical immunologist from the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, said the findings supported what healthcare professionals see in clinical practice.

“We need to think about why people present to emergency. It may be because there’s more illness, but it also may be because they’re not getting the community support to prevent and manage their illness,” said Dr Wong.

Researchers reviewed over 800,000 ED presentations in the Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service catchment area – containing 12 public hospitals including Rockhampton, Biloela and Woorabinda – over six years.

Patients presenting to an ED with asthma and allergic diseases were more likely to be female and under 14 than patients who presented for other reasons.

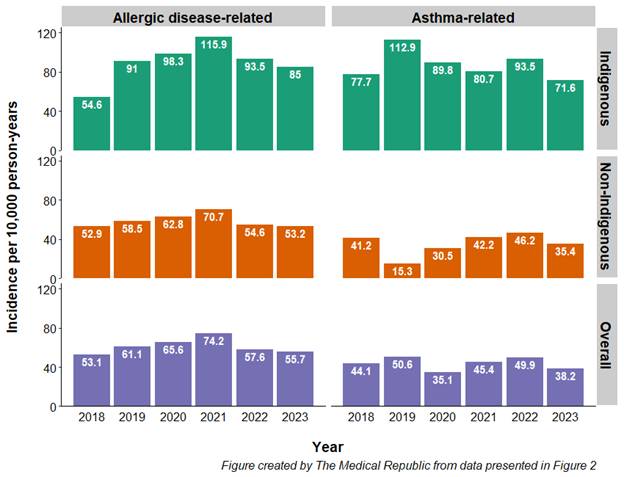

Indigenous Australians presented to ED with asthma or other allergic diseases at roughly double the rate of non-Indigenous individuals, with an incidence of 88 per 10,000 person-years compared to 40 per 10,000 for asthma and 90 per 10,000 compared to 59 per 10,000 for overall allergic disease.

Indigenous Australians had a higher incidence of ED presentations for atopic or unspecified allergies (55 versus 36 per 10,000 person-years), allergic contact dermatitis (17 versus 11 per 10,000 person-years) and allergic urticaria (4 versus 2 per 10,000 person years).

Researchers also found an increase in the incidence of allergic disease-related ED presentations over time for Indigenous Australians, but not for non-Indigenous Australians or overall – a result that surprised them.

There were no significant changes in the incidence of asthma presentations over the course of the study.

“Allergic and atopic diseases have not been traditionally recognised as an important concern among First Nations Australians. Nevertheless, there is … a growing recognition of this issue,” they wrote.

“Our findings highlight a substantial and potentially increasing burden of allergic disease among First Nations Australians living in [an area] encompassing regional, rural and remote outback areas.”

Dr Wong said there was a range of resources available for rural and remote healthcare practitioners to help reverse these trends, such as the recently launched Allergy Assist platform and the Australasian Society for Clinical Immunology and Allergy’s e-training for health professionals.

Related

urther education about the importance of early childhood exposures was also identified as a way of reducing the uneven burden of asthma and allergic diseases.

“We know that what happens in the first few years of life – things like early antibiotics, exposure to cigarette smoke, the foods that you eat and so on – can increase or reduce the incidence of allergy in children moving forward,” Dr Wong explained.

“The more we can educate our young families about how they might be able to promote a healthy lifestyle in their young kids, the better. Unfortunately, in rural and remote communities and in our First Nations communities, we know that more support is needed in this space.”

A key limitation of the study was that it did not consider all instances of acute asthma and allergic diseases among the general population who presented to an ED. For example, the researchers found no instances of food allergy-related presentations in their dataset.

A report commissioned by ASCIA estimates that over four million people across the country are affected by allergies, with this figure projected to increase to nearly eight million by 2050.