A new generation of menopausal hormonal therapies, TSECs, offers more choice

As hormone therapy for menopause begins to recover from the sensationalist and flawed interpretations of the 2002 Women Health Initiative (WHI) study,1 efforts have been renewed to develop therapies that are even safer and have even less side effects than traditional hormone treatments.

Key among these developments are tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) compounds, the key utility of which is an ability to manage vasomotor symptoms effectively, without the unwanted effects of estrogen on the breasts and the uterus, all in a pill form.2,3,4

TSECs are a combination of a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) with estrogen. Duavive, is a TSEC compromising a combination of conjugated equine estrogen with bazedoxifene, which alleviates moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms, urogenital atrophy, preserves bone and does not stimulate the endometrium so that vaginal bleeding is minimised.5 Furthermore, while studies of bazedoxifene alone have indicated an increase in venous thromboembolic disease, when combined with the conjugated estrogen no increase has been observed.6

According to Rod Baber, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Sydney Medical School, Sydney University, Duavive meaningfully extends the range of options available for menopausal hormonal treatment in Australia.

But, he says, issues still exist in general practice with respect to managing menopause effectively, mainly related to the 2002 WHI cancer and cardiovascular disease scare.

He suspects the biggest issue currently is the attitude of patients who have relatively fixed views on hormone therapy based on the WHI publicity, and a reluctance from some busy GPs to engage with such patients to alter their opinion.

“It is starting to change though,” says Professor Baber. “Male GPs who typically have felt given the history of hormone therapy that it’s a bridge too far and passed it on to their female peers, are starting to change because they see that their patients are slowly but surely starting to realise that [menopausal hormone therapy] is not the domain of a few mad monks, but is in fact standard conventional medicine”.

Professor Baber also said that GPs may have been hampered by not having some simple well-designed tools and algorithms, but this is changing too. He points to work being done by Professor Sue Davis and her colleagues from Monash University who have put together a GP toolkit for managing menopause, and published a series of updated algorithms in the journal Climateric.7

So where do TSECs fit into the picture in every day menopause management in primary care?

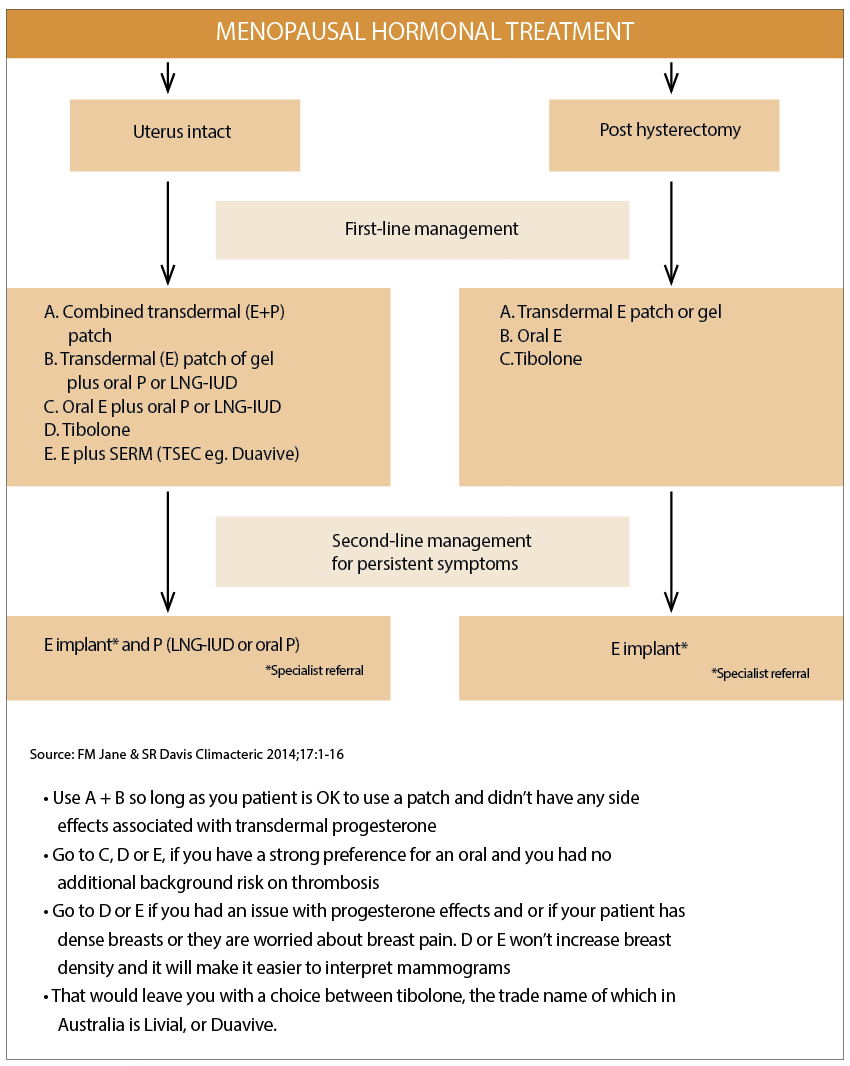

Professor Sue Davis lists the Duavive TSEC among the five key options a GP has for women who have an intact uterus (see diagram above).8

But, as Professor Baber explained to The Medical Republic, even this algorithm needed a degree of interpretation.

He says that while “you could choose to use a TSEC with any postmenopausal women” and you’d be relatively safe in that choice, the preferred starting point for most clinicians these days is still natural oestrogen plus natural progesterone. But the natural progesterone can have side effects.

“Let’s say, progesterone is making your patient sleepy, or moody, which it can do. An oral TSEC is a good alternative in this case”, he said.

In terms of orals versus transdermals, one of the key reasons clinicians will start with transdermals is to avoid the first pass effect in the liver which means there is less risk of thrombosis than with orals. But Professor Baber points out that the actual thrombotic risk with orals is quite small9 and that with appropriate screening and management, this part of the equation should not be an issue.

And if transdermal patches and natural oestrogen and progesterone are the preferred starting point for clinicians, often they aren’t as readily acceptable for patients.

According to Professor Eddie Morris, the president of the British Menopause Society, UK data suggests that women prefer a pill over a patch by a factor of 70 to 30.

According to Dr Linda Calabresi, a practising GP and Editor in Chief of The Medical Republic, patients tend to opt for oral menopausal hormone therapy for two reasons: a daily pill tends to be easier to remember than a twice weekly patch and some women feel self-conscious about wearing a patch that could be seen or felt by other people.

Says Professor Baber, “The message is that [TSECs] is a form of hormone replacement therapy you might choose to use for any women with symptoms in her 50s. And the reasons you might go towards this instead of towards natural oestrogen and progesterone would be the progesterone side effects, less breast tenderness and also patient preference.”

“Duavive’s mode of action provides the benefit of tissue selective agonist and antagonist effects which improves certain menopausal symptoms and quality of life for menopausal women with a uterus, importantly without the need of a progestin. It offers significant and sustained reduction in the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms within four weeks of initiating therapy. [In addition] it offers a frequency of breast pain, tenderness and density, rates of endometrial hyperplasia, and incidents of breakthrough bleeding and spotting, all similar to placebo groups,” Professor Baber said.

If you were to extend Professor Morris’s algorithm one or two levels based on what Professor Baber explains you would:

• Use A + B so long as you were OK to use a patch and didn’t have any side effects associated with transdermal progesterone

• Go to C, D or E, if you have a strong preference for an oral and you had no additional background risk on thrombosis

• Go to D or E if you had an issue with progesterone effects and or if your patient has dense breasts or they are worried about breast pain. D or E won’t increase breast density and it will make it easier to interpret mammograms

• That would leave you with a choice between tibolone, the trade name of which in Australia is Livial, or Duavive.

When asked to provide reasons for deciding between tibolone, which has a different mode of action to a TSEC, and a TSEC such as Duavive, Professor Baber starts to smile and says this is a good question. He explains that in some instances tibolone might be indicated if there is a lack of libido, as it is known to slightly increase libido. He prescribes both, but he says the decision for him comes down to a combination of risk assessment for his patient, patient preferences and his interpretation of the current data on both options.

At this level, the evidence isn’t yet entirely clear for either option but depending on the patient profile you could choose to go one way or another, he says. He points out that, at this stage, there is longer term trial data for tibolone.

“We think tibolone has minimal effect on the breast because it changes the action of a breast specific enzyme which stops conversion of weak estrogens into strong estrogens”, he said. This leads to less mastalgia and no increase in breast density. However, as is the case with Duavive none of the clinical trials have run for long enough for us to confidently say that breast cancer risk is not altered with long term use of either tibolone or duavive.

The Duavive data is four years old, and Professor Baber says that it is so far following a pattern that suggests it is going to be safe.

This article was written by The Medical Republic staff, including our medical editors and doctors, with the assistance of an independent medical education grant from Pfizer

References:

1. Fletcher SW et al JAMA. 2002 Jul 17;288(3):366-8

2. Pinkerton JV et al. Menopause 2009;16(6):1116-24

3. Pinkerton JV et al.Obset Gynecol 2013;121(5):959-68

4. Pinkerton Jv et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014:99(2):E189-98

5. FM Jane & SR Davis Climacteric 2014;17:1-16

6. FM Jane & SR Davis Climacteric 2014;17:1-16

7. FM Jane & SR Davis Climacteric 2014;17:1-16

8. FM Jane & SR Davis Climacteric 2014;17:1-16

9. JE Manson et al NEJM 374: 9, 803-805