New guidelines aim to optimise evidence-based, assessment and consistent care to improve the quality of life for women with PCOS

Despite polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) being the most common hormonal condition in women, many of those affected report diagnostic delays (up to two years and three health professionals) and dissatisfaction in the provision of information and support.1, 2

Health professionals, meanwhile, report knowledge gaps in areas such as: the application of the recommended diagnostic criteria, low awareness of pregnancy-related complications and psychosocial issues.3

Poor access to timely and accurate diagnosis is perhaps understandable given the heterogeneity of presentation, and the challenges inherent in the provision of targeted, individualised care.

In response to these identified systemic issues, an international collaboration has recently launched the International evidence-based guideline on the assessment and management of PCOS, in tandem with a comprehensive research translation program with global reach.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PCOS is an ancient, complex genetic disorder6 with a genomic footprint going back 50,000 years ago.7 It is postulated that the regulation of fertility may have been advantageous in the feast or famine setting8 however, in the current obesogenic environment PCOS has detrimental short and long-term health impacts.

Intrauterine events may predispose to this condition, including hyperandrogenaemia in the uterus or excess maternal hormones including anti-Müllerian hormone acting directly and indirectly on the developing endocrine system.9

Excess weight gain is significant in translating a predisposition to PCOS into clinical expression.10

PATHOLOGY

Pathological determinants of PCOS include androgen abnormalities and insulin resistance. Reproductive and metabolic features of PCOS are underpinned by insulin resistance which stimulates ovarian androgen production and decreases hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG production) thus increasing total and free androgens.11 Androgen abnormalities are present with 60 to 80% of women with PCOS showing higher concentrations of circulating free testosterone and other androgens.10

CLINICAL FEATURES

Women with PCOS present with diverse features including psychological (anxiety, depression, poor body image),12-14 reproductive (irregular menstrual cycles, hirsutism, infertility and pregnancy complications)15 and metabolic features (insulin resistance (IR), metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, type 2 diabetes (TDM2) and cardiovascular risk factors).16, 17 Presentation varies across the lifespan and between ethnicities.

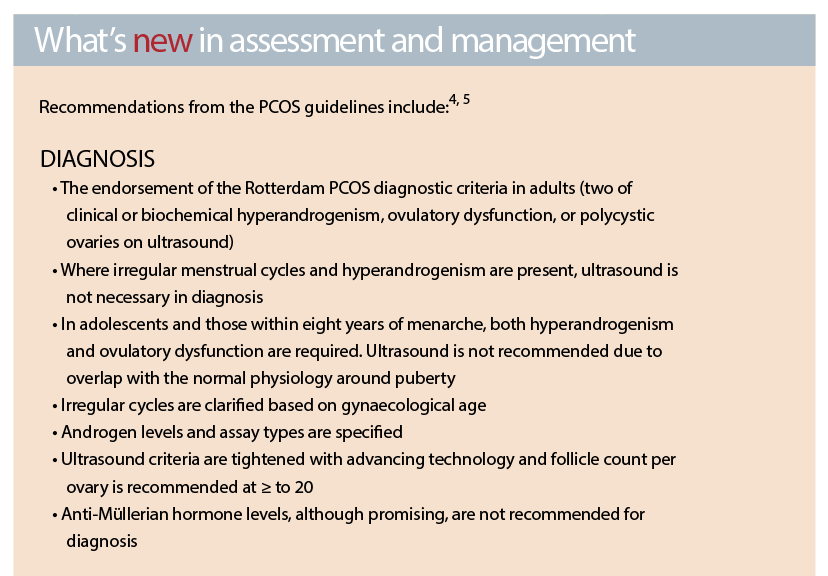

DIAGNOSIS

GPs should have a high level of suspicion of PCOS in women who present with: menstrual irregularity, overweight or obesity, fertility issues, acne or hirsutism, prediabetes, gestational diabetes or early onset T2DM.

Rotterdam criteria should be used in adults.

Rotterdam diagnostic criteria requires two of:

1. Oligo- or anovulation

2. Clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism

3. Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound and exclusion of other aetiologies including: Thyroid disease, hyperprolactinemia, FSH (if premature menopause is suspected) and non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, generally due to low body fat or intensive exercise, should also be excluded clinically and with LH and FSH levels.

ADOLESCENTS

In adolescents and those within eight years of menarche, 1 and 2 are required with 3 not recommended due to lack of specificity in this life stage. The value and optimal timing of assessment and diagnosis of PCOS in adolescence should be discussed, considering diagnostic challenges at this life stage and psychosocial and cultural factors.

When commencing hormonal contraception in adolescents, and diagnosis is unclear, take a baseline assessment of clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism and cycle patterns before commencement of hormonal contraception and consider future reassessment.

If baseline assessment is abnormal, potential increased risk of PCOS could be discussed with the patient and future reassessment planned.

ADULT WOMEN

Reproductive years

Irregular menstrual cycles (>35 days of <21 days) in adult women clinically reflect ovulatory dysfunction. However, ovulatory dysfunction can still occur with regular cycles and luteal phase progesterone levels can be measured to assess ovulation when PCOS is clinically suspected and cycles are regular.

Peri/menopausal women

Diagnosis at this life-stage may be based on a history of oligomenorrhoea and hyperandrogenism during the reproductive years. In addition, whilst some aspects of PCOS improve at this life-stage, the risk of metabolic abnormalities may persist.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FEATURES

• Emotional health screening using evidence-based screening tools on assessment as needed

• Treatment of factors such as hirsutism and excess body weight, which can negatively affect quality of life, are important as re conventional treatments (cognitive behavioural therapy, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy) where needed for management of mood disorders. It is equally critical to emphasise the role lifestyle can play in improving emotional wellbeing18, 19

• Consider a mental health care plan and referral to psychologist/psychiatrist when needed

OLIGO/AMENORRHEA

• Lifestyle changes (5-10% weight loss through structured exercise and calorie restriction)

• COCPs (low oestrogen doses, i.e. 20 micrograms may have less side effects and second generation progestins are associated with lower risk of thromboembolism)

• Cyclic progestins to induce withdrawal bleed if COCPs not desired or contraindicated (i.e. 10mg medroxyprogesterone acetate 10-14 days every two to three months if no cycle in interim)

• Metformin improves menstrual cyclicity and ovulation

HIRSUTISM

• Cosmetic therapy (laser or electrolysis) is considered first line

• COCPs are first line if cosmetic therapy unsuccessful. If ineffective after six to nine months, an antiandrogen can be added (i.e. spironolactone or cyproterone acetate)

• Ensure adequate contraception when prescribing antiandrogens

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT AND CARDIOMETABOLIC RISK REDUCTION

• Prevention of weight gain through ongoing attention to lifestyle and weight monitoring.

• No specific diet is recommended

• Encourage reduction of sedentary behaviour and increase in physical activity

• If overweight or obese, encourage 5-10% weight loss through structured exercise and calorie restriction

• Metformin aids prevention of weight gain, assists lifestyle induced weight loss and prevents diabetes onset

Consider referral if appropriate to: dietitian (tailored dietary advice, education, behavioural change support), exercise physiologist (exercise motivation, education), psychologist (motivational interviewing, behaviour management techniques, emotional health and motivation) and/or group support (diet and exercise program).

USE OF METFORMIN

Metformin may also be used to:

• Prevent weight gain, IGT and T2DM in PCOS where lifestyle programs fail

• Improve menstrual irregularity in women who do not desire or have contraindications to the use of COCPs

• Assist reproduction in women who choose to trial this agent, after counselling on options and understanding there are other agents with greater efficacy

• When indicated, metformin can be started at a low dose (500mg daily) to enhance GI tolerance with dosage titrated (by 500mg every two to four weeks as tolerated) to a maximum dose of 1500 to 2000mg daily

FAMILY PLANNING

• Advise early family planning and initiation where possible

• Emphasise prevention of weight gain prior to conception

• Encourage weight loss if overweight. If a significant weight loss occurs, consider a period of three to six months of weight stability prior to conception

INFERTILITY

• Ovulation induction techniques include pharmacotherapy with letrozole, clomiphene citrate ± metformin, gonadotropins or laparoscopic ovarian drilling

• Specialist referral for consideration of assisted reproductive techniques is important in women who fail to conceive after 12 months and earlier in women over 35 years

• IVF is not commonly needed in infertility due to PCOS alone.

PRECONCEPTION AND EARLY PREGNANCY

• Increased risk of pregnancy complications in women with PCOS

• Preconception and early antenatal lifestyle intervention, assessment of BMI, blood pressure and OGTT are recommended in all women with PCOS to reduce the risk of developing GDM, pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia

METABOLIC RISK MANAGEMENT

• Screen all women for impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes pre-conception or early in pregnancy and in all women at 24 to 28 weeks

• Check blood pressure once a year if BMI is less than 25kg/m2 and at every visit if BMI is equal to or greater then 25kg/m2

• Measure fasting lipids at diagnosis and monitor based on additional obesity and cardiovascular risk factors

• OGTT at baseline in all women with PCOS, then assess every one to three years, influenced by the presence of other diabetes risk factors. OGTT should be performed at baseline in high risk women with PCOS (including a BMI >25kg/m2 or in Asian >23kg/m2, history of impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance or gestational diabetes, family history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension or high-risk ethnicity)

CONCLUSION

The coupling of a genetic disposition with an obesogenic environment is contributing to the rise in prevalence of PCOS. The PCOS guideline (2018) aims to optimise evidence-based, assessment and consistent care that meets the needs and improves the quality of life for women with PCOS.

The guideline and translation program were developed with health professionals including GPs and consumers whilst targeting the priorities for women with PCOS.

The guideline strongly recommends that health professionals focus on patient priorities and empowerment through education and fostering a partnership care approach to improve health outcomes.

Better alignment of primary care practice with evidence-based diagnosis and management approaches will contribute to reduced reproductive, metabolic and reproductive impacts in affected women across their lifespan and improve patient experiences.

Dr Rhonda Garad (PhD) is Research Translation Lead at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation

Professor Helena Teede is Executive Director at Monash Partners Academic Health Research Translation Centre; Director at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University; and Endocrinologist at Monash Health

References:

1. Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Dunaif A, Dokras A. Delayed Diagnosis and a Lack of Information Associated With Dissatisfaction in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017;102(2):604-12.

2. Gibson-Helm M, Tassone E, Teede H, Dokras A, Garad R. The Needs of Women and Healthcare Providers regarding Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Information, Resources, and Education: A Systematic Search and Narrative Review. 2018;36(01):035-41.

3. Dokras A, Saini S, Gibson-Helm M, Schulkin J, Cooney L, Teede H. Gaps in knowledge among physicians regarding diagnostic criteria and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2017;107(6):1380-6.e1.

4. Teede H, Legro R, Norman R. A Vision for Improving the Assessment and Management of PCOS through International Collaboration. 2018;36(01):003-4.

5. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018.

6. Barber T, Franks S. Genetic basis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;5(4):549-61.

7. Ünlütürk U, Sezgin E, Yildiz BO. Evolutionary determinants of polycystic ovary syndrome: part 1. Fertility and Sterility. 2016;106(1):33-41.

8. Fessler DMT, Natterson-Horowitz B, Azziz R. Evolutionary determinants of polycystic ovary syndrome: part 2. Fertility and Sterility. 2016;106(1):42-7.

9. Tata B, Mimouni NEH, Barbotin AL, Malone SA, Loyens A, Pigny P, et al. Elevated prenatal anti-Mullerian hormone reprograms the fetus and induces polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood. Nat Med. 2018.

10. Norman R, Teede H. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Medical Journal of Australia. 2018;In press.

11. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Papavassiliou AG. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;12(7):324-32.

12. Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Medicine. 2010;8:41.

13. Deeks A, Gibson-Helm M, Teede H. Is having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) a predictor of poor psychological function including depression and anxiety. Hum Reprod. 2011;Advance access published March 23, 2011.

14. Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Medicine. 2010;8(1):41.

15. Boomsma C, Eijkemans M, Hughes E, Visser G, Fauser B, Macklon N. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12(6):673-83.

16. Apridonidze T, Essah P, Luorno M, Nestler J. Prevalence and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;90(4):1929-35.

17. Legro R, Kunselman A, Dodson W, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: A prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metababolism. 1999;84(1):165-8.

18. Thomson RL, Buckley JD, Lim SS, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Norman RJ, et al. Lifestyle management improves quality of life and depression in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94(5):1812-6.

19. Dokras A, Stener-Victorin E, Yildiz BO, Li R, Ottey S, Shah D, et al. Androgen Excess- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society: position statement on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and eating disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome.(Report). Fertility and Sterility. 2018;109(5):888.