One of the most powerful treatments in medicine is coming to a door near you – depending on where you live

Stroke is no longer an irretrievable occurrence, says radiologist Professor Peter Mitchell.

“We now regularly see people coming in completely paralysed in their arm and leg, unable to speak and who have lost half their vision. We treat them, and then we see patients improve on the table – and the next day they go home completely neurologically intact,” Professor Mitchell told The Medical Republic.

Director of the NeuroIntervention Service at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Professor Mitchell says the improved outcomes are due to emergency thrombectomy, heralded by many as the “second revolution” in stroke care.

The minimally invasive procedure involves removing the clot under direct angiographic visualisation after thrombolysis, and has recently become the standard of care for large vessel acute ischaemic stroke after a raft of RCTs published in 2015.

The first revolution in stroke reperfusion was thrombolysis using tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), says Associate Professor Bruce Campbell, head of hyperacute stroke in the Department of Neurology, Royal Melbourne Hospital.

“For the first time there was a treatment that could change a patient’s trajectory towards disability,” he says. “Beyond the effect of the drug itself, it caused a shift in mindset – stroke was now clearly an emergency that required rapid attention and treatment, and that brought other improvements in care.”

Now, endovascular thrombectomy is the second major shift in stroke reperfusion, Professor Campbell says, with a substantially larger absolute benefit in reduced disability than tPA.

The number needed to treat (NNT) to reduce disability is 2.6 patients with thrombectomy, and five to allow one extra patient an independent recovery, he tells TMR, one of the most powerful treatment effects in any field of medicine.

“As with tPA, the excitement around thrombectomy has the potential to drive much broader interest and improvement in stroke systems of care.”

Yet according to Professor Mitchell, many in the community still have a sense of fatalism around stroke, without realising this extraordinarily important development in treatment has occurred.

“If you get to the hospital quickly and are diagnosed quickly, there are treatments available that dramatically improve your chance of making a complete recovery.”

Just as in the case of heart attack, the key message for patients and clinicians is, “time, time and time,” Professor Mitchell says.

A certain volume of brain will be infarcted at the time of presentation, but the earlier reperfusion occurs, the smaller the permanent volume of brain loss, he says.

It’s the patients who get the procedure done early and with a good unblocking of the artery that typically have the “fantastic outcomes” and can go home within a day or two, he says.

But evidence is showing thrombectomy can also confer some benefit in patients who present at a later stage, perhaps three, six or even eight hours after symptom-onset.

“They may still end up in their own home, independent, doing all activities of daily living on their own, whereas if they hadn’t had the treatment they may end up dependent in a nursing home.”

THE ABOUT-FACE

Before 2015, trials of mechanical thrombectomy had provided little convincing evidence to move away from the standard care at the time – either no treatment or thrombolysis with tPA.

While intravenous tPA improved the chance of independent function at 90 days across a range of ages and severity, it resulted in early reperfusion in only 13% to 50% of patients with occlusions of the intracranial internal carotid artery and/or the first segment of the middle cerebral artery.1

It was only after data from the large MR CLEAN trial began to show the superiority of thrombectomy on neurological outcome that a new picture began to emerge2.

In fact, the results were so dramatic the study was stopped early.

Another four multicentre, open-label RCTs were published soon after: the Canadian ESCAPE, Australian EXTEND-IA, Spanish REVASCAT and SWIFT PRIME.

These trials, using second-generation devices, improved selection criteria and a more efficient workflow, showed a substantial improvement in neurological outcome after an ischaemic stroke compared to a standard intravenous tPA alone.

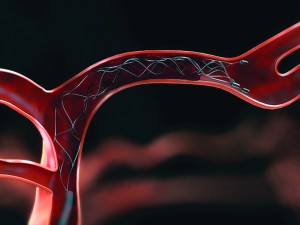

The main devices used in these trials, and in current Australian practice, are generically called stent retrievers.

“They look a bit like a stent you’d put in a blocked artery in the heart,” explained Professor Mitchell. “But instead of being left behind, we deploy the stent into the blood clot inside the brain artery.”

“Then we remove the stent, which remains on the wire, while applying aspiration to the catheter – and you remove the blood clot entirely from the body.”

These newer generation devices have higher recanalisation rates and lower complication rates than their predecessors, and higher rates of reperfusion than intravenous tPA by itself.

SUBGROUPS

But because most of the first five studies were stopped early, gaps remained in our knowledge.

For instance, it wasn’t clear how beneficial thrombectomy would be for clinically important subgroups such as the elderly, those with mild deficits and those who weren’t eligible for tPA.

But by pooling data from the 1300 participants in the studies, the researchers were able to answer some of these questions3.

This team, known as the HERMES collaboration, found significant benefits to thrombectomy in patients older than 80 years, those receiving therapy five hours after symptom onset and those not given intravenous alteplase.

“In EXTEND-IA we selected the very best potential candidates, but now we know that even beyond that you still get significant benefits,” says Professor Campbell, who led the EXTEND-IA trial and co-authored the HERMES trials.

While absolute rates of functional independence at three months were higher for patients younger than 80 years, endovascular thrombectomy was still superior to standard care in the older group.

Patients who weren’t thrombolysed also experienced a substantial benefit from thrombectomy, they found.

And surprisingly, those with the most severe deficits weren’t necessarily those who benefited most from thrombectomy, Professor Campbell and his co-authors found. Instead, there was a similar effect on disability across the spectrum of severity.

Of every 100 patients treated with the therapy, 38 will end up with less severe disability than if they’d undergone thrombolysis, and another 20 will achieve functional independence, they found.

There was also no suggestion of other unintended side effects. Intracranial haemorrhage, radiological intracerebral haematoma and mortality rates were no higher than medical therapy alone.

TIME IS BRAIN

Now the HERMES team have published yet another study, quantifying just how important early treatment really is.4

The results, published in JAMA, have sparked calls to revamp stroke care access across the country, ensuring patients gain access to thrombectomy services as quickly as possible.

For every hour that arterial puncture and substantial reperfusion were delayed after symptom onset, the likelihood of disability increases.

The study authors estimated that for every 1000 patients achieving substantial endovascular reperfusion, 15 minutes’ shorter “door-to-reperfusion time” would result in 39 less-disabled patients at three months.

Another 25 would also achieve functional independence by three months.

While it is clear that early treatment yields superior results, the study also found that thrombectomy still offered some benefits over a much longer window of time.

Patient outcomes were significantly better up to 7.3 hours after symptom onset, with figures suggesting it might even extend to eight hours.

One option to improve outcomes may be for stroke centres to meet aggressive goals such as 60 minutes from arrival to arterial puncture, and 90 minutes from arrival to the achievement of substantial reperfusion, an accompanying editorial suggests.

According to figures from the Stroke Foundation, around 50,000 new or recurrent strokes occur in Australia each year.

Around one in 10 of those have the type of stroke that might benefit from thrombectomy. Unfortunately, access to these specialist services in Australia is still subpar and coverage is patchy.

Victoria has a state-wide system designed to deliver even rural patients to a centralised stroke centre, as well as a telemedicine system which covers a network of smaller, rural hospitals.

Subsequently, around 95% of the state’s stroke patients have access to healthcare professionals who can provide thrombolysis if appropriate, and can be transferred to the city if endovascular clot retrieval is needed, says Professor Campbell.

Adelaide and Perth are also making good progress in providing the treatment, but Australia is hamstrung by its geography. When time is of the essence, vast distances between people’s homes and the proceduralist is a difficult barrier to overcome, Professor Campbell says.

Beyond that, having the workforce to provide 24/7 service is another issue, he says.

“In Sydney, it’s a bit of a luck of the draw where you happen to have your stroke and when you happen to have your stroke as to whether you’ll get access,” Professor Campbell says.

Of course, cost is one crucial barrier to wider implementation.

“One of the thing we’re looking at, at the moment, is a true cost-effectiveness analysis of this technique,” Professor Mitchell says. “The information that’s been looked at already shows that when you consider that you’re twice as likely to not just survive but be independent and back at home if you have this treatment as opposed to if you don’t.”

People who aren’t independent and back at home are in a nursing home or some sort of facility requiring expensive care, and preliminary data from here and abroad suggests it is cost effective for the community, he says.

“Even though the procedure is moderately costly and ambulance transfers to get someone from a remote site to our centre is obviously a cost, if you get someone back into their own home compared to being dependent for many years in a high facility care that’s a cost saving overall,” Professor Mitchell says. “Although we know it is a cost effective technique for the community, it’s expensive for us because there’s expensive equipment, there’s investment in staff and the consumables that are needed to do the treatment,” he says.

All up, this procedure costs the centre around $10,000 per patient, he says.

“Overall, when you look at the cost of hospital stays and nursing home et cetera, that’s recouped within three to six months. But that comes from a different budget.”

However, improvements are needed across a number of fronts to provide the best hope for Australian stroke patients.

Specialist ambulances are being trialled in some metro Australian cities that are equipped with CT scans to more quickly determine whether a patient needs to be transported to a specialist centre.

In the meantime, the fundamental message about time remains the same.

Time is crucial, even more so than for myocardial ischemia, Professor Mitchell says.

The community needs to be aware of the FAST stroke awareness message, he says.

That is: Face, check their face, has their mouth drooped? Arm, can they lift both arms? Speech, is their speech slurred? Do they understand you? Time, time is critical.

Any of those signs should be the cue for patients to call 000 immediately.

“But really it is about getting the artery open quickly, and that’s why thrombolysis is still the basis of everything we do,” he says.

“In Australia, we give tPA to 7% of all ischaemic stroke patients,” Professor Campbell says. “In most active centres that proportion is up to 20%, so I think there’s room for a three-fold increase in the use of thrombolysis in Australia.”

Right now, only 26% of thrombolysis patients receive the treatment within 60 minutes of emergency department arrival – which is lagging behind the UK and US, Professor Campbell says.

“Stroke is one of the most time critical medical emergencies. Every minute that elapses without opening the artery means more brain cells dying and a worse stroke outcome, so going faster probably gives the best “bang for buck” to improve patient outcomes,” he says.

Thrombectomy is useful in about a third of the tPA patients, plus a few who are not eligible for tPA, he says.

And these represent the patients with the most severe strokes that have the highest risk of disability and death if left untreated, and a group where tPA is less effective at dissolving these large blood clots.

“For example, if you’ve got patients taking warfarin or some other anticoagulant and they can’t have thrombolysis, they can still potentially have thombectomy,” Professor Campbell explained.

While thrombectomy is applicable only for a subset of the patients, it’s still important that we get the implementation done right in Australia, he says.

“Yes it’s only 10% of all stroke patients, but still they’re the most severely affected and so the most at risk of disability,” Professor Campbell says. “So it’s a lot more significant than just the tiny fraction it might appear at first glance. These are the patients that end up in nursing homes if you don’t treat them properly.”

References: