Up to one in eight palpable nodules are malignant. Here are the tests to order and the treatment options for patients with the condition.

Thyroid nodules are very common and can be detected in up to 65% of the general population.i

They are defined as discrete lesions within the thyroid gland that are radiologically distinct from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma. Most of these nodules will be benign and can be safely managed with surveillance. The primary purpose behind investigation of thyroid nodules is to determine the likelihood of thyroid malignancy. The chance of malignancy in a palpable thyroid is about 4-6.5% 1

Thyroid nodules may come to the attention of the patient or the GP during routine examination or as a consequence of other investigations such as a CT or MRI of the neck, or carotid ultrasound or positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

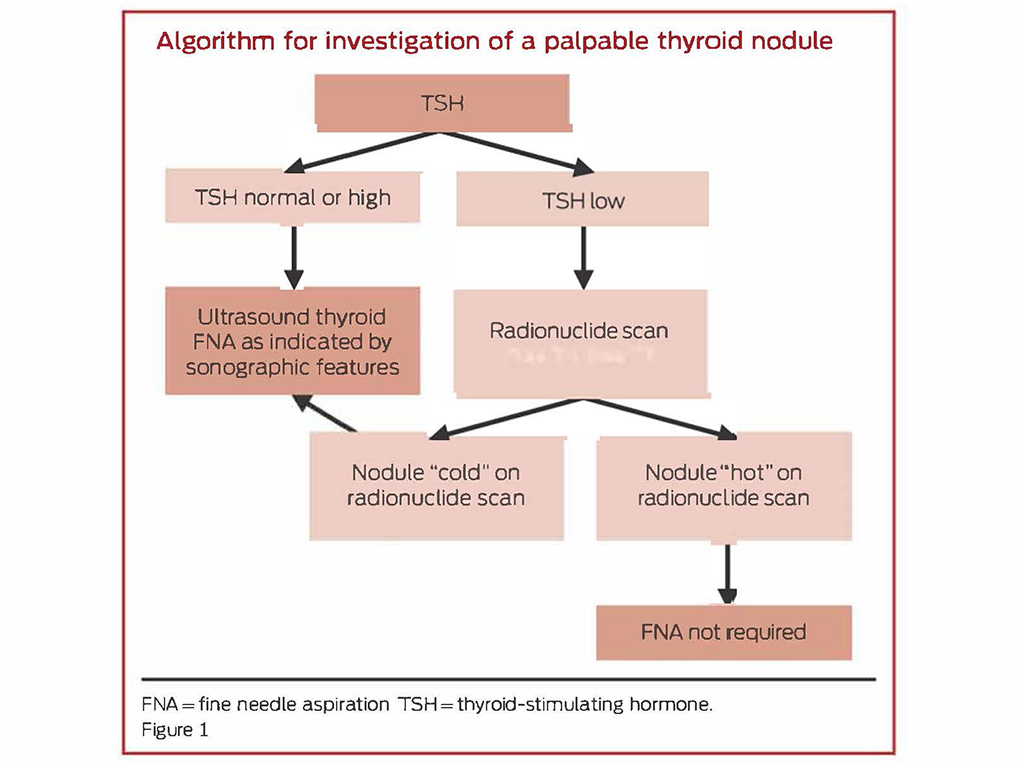

A pathway for the investigation and management of thyroid nodules is outlined below (Figure 1).2

Investigation and diagnosis of thyroid nodules

Once a thyroid nodule is identified, subsequent investigations are based on history and examination, and biochemical and ultrasonographic parameters.

An ultrasound and a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level should be considered as first-line investigations for all patients presenting with a thyroid nodule.

History and examination

There is a low accuracy for predicting the chance of cancer in a thyroid nodule based solely on history and examination. There are, however, several features that are suggestive of an increased chance of malignancy. These include a history of rapid growth in a neck mass and other red flag signs including symptoms that may represent local invasion into structures that surround the thyroid. These would include difficulty swallowing, discomfort on swallowing and new-onset hoarseness, which might represent a vocal cord palsy.

Additionally, there are several subgroups of patients who are at significantly increased risk of carcinoma, including children, adults who are less than 30 years of age, and patients who have either a family history of thyroid malignancy or a previous history of head and neck irradiation.

Biochemical investigation

TSH is the most important biochemical investigation. Free T4 and T3 levels, thyroid peroxidase antibodies and thyroglobulin are unlikely to add to the clinical picture and are not routinely required 3

- Low TSH

- In the setting of a low TSH, the possibility of a hyper-functioning nodule is increased

- The next appropriate investigation is a thyroid scintigraphy scan typically using 123-I iodine as the radioisotope

- Thyroid auto-antibodies will help to determine if the diagnosis is Graves’ disease

- A hyper-functioning nodule is unlikely to represent a malignancy and does not require further investigation with a fine needle aspirate (FNA) biopsy

- Normal or high TSH

- A biopsy is required for all nodules that meet the sonographic criteria for sampling

Ultrasonographic investigation

Ultrasound is the best modality for assessment of a thyroid nodule. It also allows evaluation of not just the thyroid nodule but also any central or lateral neck lymphadenopathy.

The ultrasound will be able to assess the size of the nodule, location of the nodule, composition (solid, cystic or spongiform), echogenicity, margins of the nodule, any calcifications, shape (height vs width) and vascularity.

The American Thyroid Association and a number of other professional groups have devised similar but not identical tiered systems for identifying which nodules should be biopsied, based on their chance of malignancy based on a number of sonographic features.4 One of the more recent guidelines is from the American College of Radiology and is called the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TiRADS).5

Under this system, points are assigned to a nodule based on five ultrasonographic features. The sum of these points determines the TiRADS score, which enables easier classification of a nodule. Certain suspicious sonographic features are assigned points, and the nodules are categorised as TiRADS 1-5 based on total points with increasing change of malignancy. Based on this score, each nodule is assigned an estimated cancer risk and a recommendation regarding proceeding with FNA biopsy or surveillance 6

Nodules that do not meet sonographic criteria for FNA biopsy should be monitored. The frequency of evaluation depends on sonographic features of the nodules.

It is recommended that periodic ultrasonography is initially followed up at:

- Six to 12 months for sub-centimetre nodules with suspicious characteristics

- Twelve to 24 months for nodules with low to intermediate suspicion on ultrasound

- Two to three years for low-risk nodules

Histopathological investigation

There are six major categories of results that are obtained from FNA and each category directs subsequent management. 7

- Bethesda I Insufficient or Non-Diagnostic

- This FNA is non-diagnostic and requires a further FNA biopsy, typically at six weeks, for re-evaluation. If a second FNA is non-diagnostic, a core biopsy can be considered.

- Bethesda II Benign

- Equates to a benign nodule and they can be followed up with surveillance alone unless there is substantial growth in a nodule or if the nodule develops suspicious ultrasonographic features. If the nodules are re-biopsied and are again benign, no further malignancy surveillance is required. It is reasonable to continue ultrasonographic surveillance if there is concern about compressive symptoms.

- Bethesda III Follicular lesion or atypia of undetermined significance

- This category generates controversy because of inconsistent usage across different clinicians and institutions. AUS/FLUS was defined for use as a category of last resort, with the expectation that 7% or fewer of FNAs would receive this diagnosis (Bethesda). The Bethesda consensus publication estimates that such a nodule would be associated with a low risk of malignancy (5–15%) and, in the absence of other suspicious features, could be managed with a repeat FNA, typically at three months

- If there is ongoing uncertainty, a diagnostic lobectomy should be considered.

- Bethesda IV Follicular neoplasm

- A follicular entity can be determined as completely benign only when the whole lesion can be histopathologically assessed, as the cells in a follicular adenoma appear almost identical to those in a follicular malignancy. The lesion can be diagnosed as malignant only if the cells breach the capsule of the lesion.

- This FNA finding is thought to warrant surgery because of an estimated 15–30% risk of malignancy.

- Bethesda V Suspicious for malignancy

- This category includes lesions that are suggestive of, but not definitive for, papillary thyroid carcinoma or other malignancies. Nodules that fall within this category have a 50-75% risk of malignancy or noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). NIFTP was previously categorised as a noninvasive follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer but have recently been reclassified as a benign entity. These patients should be referred for surgery.

- Bethesda VI Malignant

- This includes papillary cancer, medullary cancer, thyroid lymphoma, anaplastic cancer and cancer metastatic to the thyroid. These lesions should be referred for surgery.

| The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology | ||

| Diagnostic Category | Risk of Malignancy (%) | Usual Management |

| Category 1: Non-diagnostic or unsatisfactory Cyst fluid onlyVirtually acellular specimenObscuring blood, artifacts | 0-5 | Repeat FNA biopsy in three months |

| Category 2: Benign Benign follicular noduleChronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditisGranulomatous (subacute) thyroiditis | 0-3 | Clinical or sonographic follow-up |

| Category 3: Lesion of undetermined significance Focal nuclear atypiaPredominance of Hurthle cellsMicrofollicular pattern in a hypocellular specimen | 10-30 | Repeat FNA in three months; if ongoing uncertainty consider lobectomy |

| Category 4: Follicular neoplasm or Suspicious for follicular neoplasm Crowded and overlapping follicular cells, some or most of which are arranged as microfollicles | 25-40 | Lobectomy |

| Category 5: Suspicious for malignancy Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinomaSuspicious for medullary thyroid carcinoma Suspicious for metastatic carcinomaSuspicious for lymphoma | 50-75 | Lobectomy or total thyroidectomy |

| Category 6: Malignant Papillary thyroid carcinomaPoorly differentiated carcinomaMedullary thyroid carcinomaUndifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma | 97-99 | Total thyroidectomy |

Treatment

Patients with cytologically suspicious or malignant nodules (i.e., Bethesda classes 5 and 6) should generally be referred for surgery and this will entail a lobectomy for smaller tumours or a total thyroidectomy +/- central neck dissection for larger tumours or those with evidence of extrathyroidal extension or lymph node metastases.

When surgery is considered for indeterminate nodules (i.e., Bethesda classes 3 and 4), lobectomy is preferred.

When clinical, cytological or sonographic findings are discordant, a multidisciplinary-team approach is recommended. Surgery for large (greater than 4cm) cytologically benign nodules should be considered if malignancy is considered possible, in the setting of new suspicious sonographic features (despite cytological findings) or compressive symptoms.

Alternative treatments

Recently, image-guided minimally invasive techniques have been proposed and may be considered for treating clinically relevant benign thyroid nodules8. Radioiodine therapy can also be considered for patients with hyperfunctioning nodules whose biochemical testing shows hyperthyroidism.

Conclusion

The initial evaluation in all patients with a thyroid nodule includes a history and physical examination, neck ultrasonography and a measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone.

The decision to proceed to FNA biopsy should be based on a combination of ultrasonographic features as well as the degree of clinical suspicion from the history regarding the possibility of an underlying malignant process.

References

- Ross DS, Mulder JE, Cooper DS (2020). Diagnostic approach to and treatment of thyroid nodules. UpToDate. Retrieved 1 May 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-and-treatment-of-thyroid-nodules

- Bailey S, Wallwork B. Differentiating between benign and malignant thyroid nodules; an evidence-based approach in general practice. AJGP. Nov 2018; 47(11): 770-714

- Wong R, Farrell SG, Grossmann M. Thyroid nodules; diagnosis and management. MJA. July 2018;209(2):92-98

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer; the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26(1):1-133

- Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, Hoang JK, Berland LL, Teefey SA et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): White paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14:587-595

- Durante C, Grani G, Lamartina L, Filetti S, Madel SJ, Cooper DS. The diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. JAMA. March 2018;319(9):914-924

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopatholog. Thyroid. Nov 2009; 19(11):1159-65

- Grani G, Sponziello M, Pesce V, Ramundo V, Durante C. Contemporary thyroid nodule evaluation and management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Sep 2020;105(9):2869-2883

Dr Julia Crawford is an ENT-trained head and neck surgeon who consults through Sydney ENT Clinic and operates at the St Vincent’s Hospital Campus in Sydney.

[i] Durante et al. The diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules; A Review. JAMA 319(9); 2018: 914-924

Cibas ES et al. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2009;19(1); 1158-65