Medicare is a mass of contradictions and perverse incentives that requires more than tinkering.

In a recent report by the Grattan Institute, the authors describe the Medicare schedule fee as a “fair fee”.

“3.1 There is no limit on what doctors can charge for a service

“Medicare subsidises the cost of providing healthcare services. It sets a schedule fee for each service – defined by the government as a fair fee. The government, through Medicare, then rebates patients either fully or partially for that schedule fee.72”

The report then makes numerous recommendations on the back of the “fair fee” statement.

It is worth unpacking the fair fee argument because I doubt many GPs would agree that the schedule fee is fair.

Pursuant to Section 51(xxiiiA) of the Australian Constitution and numerous High Court decisions, it is settled law in this country that the commonwealth government has no constitutional authority to set or control doctors’ fees, so it does neither.

In practical terms, what this means is that Medicare is a patient insurance scheme, not a doctor payment scheme, and this core tenet of Medicare is expressed in the enabling legislation by references to an “eligible person”.

Only an “eligible person” can ever be entitled to a Medicare benefit, and an eligible person is a patient, not a doctor.

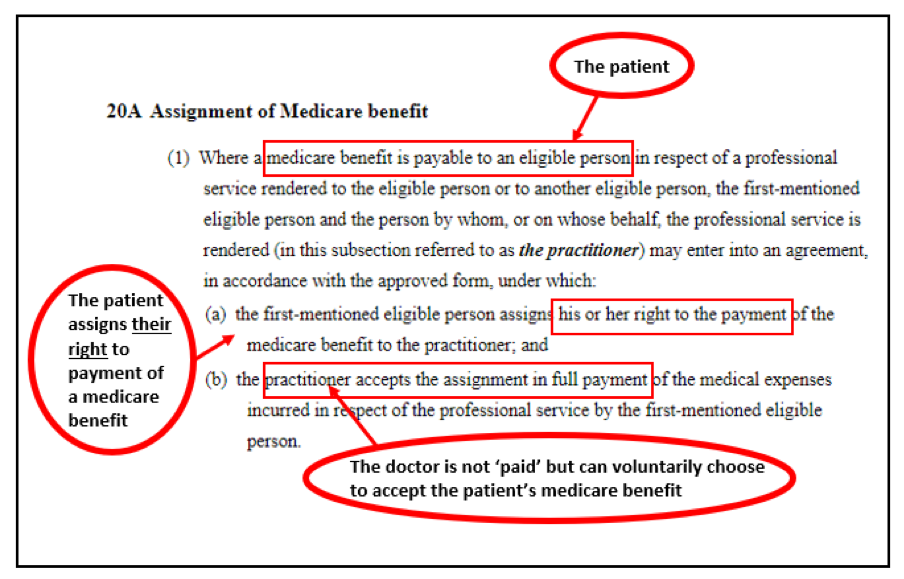

The bulk-billing law, Section 20A of the Health Insurance Act 1973 could not be clearer in demonstrating this. Here it is with relevant phrases highlighted.

Stepping back in time for a moment, use of the word “fee” is nothing more than a historic legacy. The original schedule of benefits was derived from the AMA’s “List of the most common fees” and the word fee has endured.

While titled the Medicare Benefits Schedule, rather than the Medicare Fees Schedule, it is true that the word fee still appears when describing the 100% benefit. Replacing the word fee with “benefit” throughout the MBS would alleviate a lot of confusion, but we are stuck with it for now.

However, a legal definition does exist. In 1994 the High Court settled certain key definitions around Medicare benefits, characterising them as statutory gratuities. A type of welfare payment, if you like. Therefore, when a GP bulk-bills and receives the Medicare schedule fee for say, item 23, that GP is not receiving a fee but an assigned benefit.

It’s a bit of semantic gymnastics and surprisingly complex, but further holes in the “fair fee” argument become clearer once it is understood that Medicare benefits bear little relationship to the actual costs of providing services. This is attributable to the fact that benefits are not pegged to any consistently applied, evidence based, mathematical formula, and never have been. A major project undertaken by the government between 1997 and 2000 resulted in a formula being arrived at, but unfortunately, various doctor groups ensured this excellent body of work would never be implemented.

It is for this reason that we continue to see “unfair” fees across the MBS. My company has been coding day surgery procedures for years. This work involves reading the operating theatre reports which record “time in” and “time out” of theatre. I don’t know how anyone could possibly argue that the schedule fee is a fair fee when 10 minutes with a GP attracts a schedule fee of $39.10, but a 10-minute cataract operation attracts a schedule fee of $791.45.

Evidence has also shown the complexity of medical fees in Australia, reporting that a single medical service can be the subject of over 30 different rebates, having vastly different dollar values depending on the payer.

For example, the schedule fee for a common knee replacement MBS item is $1371.25, but the commonwealth government, when paying under its ComCare workers compensation scheme, reimburses the very same item at $4230.

It makes absolutely no sense to suggest that $1371.25 is a fair fee for one group of patients, but $4230 is a fair fee for another group of patients having the exact same operation.

This also challenges the proposal in the Grattan Report to “remove rebates for specialists who charge more than twice the Medicare schedule fee”.

While no doubt well intentioned, it is important to always remember that the Medicare rebate is an entitlement for the patient not the doctor, so removing rebates from the doctor will likely push patient out-of-pocket costs up, which is the opposite of what the authors intend. Patients have a legal right to choose their doctors. So, if a patient chooses a specialist who charges more than twice the schedule fee and they like them and want to go ahead with treatment, they will have no option but to pay the fee charged, but will be denied their Medicare rebates. This may be particularly problematic for patients living in remote locations or in circumstances where there aren’t many specialists to choose from. It will also likely increase non-compliant billing. Specialists will want to enable Medicare benefits for their patients, so some will charge separate fees (not necessarily illegally) to get around the barrier. I can see exactly how that will happen already.

Additionally, given double the schedule fee for a common knee replacement is $2742.50, if the Grattan proposal were to be introduced, it would create a perverse incentive for orthopaedic surgeons to stop providing services to the general public, and instead focus on workers compensation patients. There’s plenty of work, and the surgeons will receive more than three times the schedule fee from the same payer – the commonwealth government – for doing the same operation, and they won’t be accused of egregious billing.

Medical fee and rebate setting is a complex business, and everyone wants solutions to consumer OOPs. But complex problems always require multi-pronged, evidence-based solutions, and it therefore gives me no joy to agree with the statement in the Grattan report that “The government should not increase Medicare rebates to reduce out-of-pocket payments…”

The evidence we have suggests Medicare leakage is higher than all previous estimates, and may now be in the vicinity of $7-$8 billion per annum, with non-compliant billing out of control. So it would be irresponsible to increase rebates in the short term.

The starting point is to stop tinkering with Medicare and get to work on critically important structural reform.

Dr Margaret Faux is a health system administrator, lawyer and registered nurse with a PhD in Medicare compliance, and is the CEO of AIMAC, which offers courses and explainers on legally correct Medicare billing.