Ivermectin has been given to vast numbers of patients based on a study whose profound problems escaped us for six months.

Ivermectin is an antiparasitic medication used to treat various types of worms and similar diseases.

It’s pretty safe, widely in use across the world, and in most ways a useful medication to have on hand if you think you’ve been exposed to contaminated human faeces, or if you just need to disinfect your sheep.

However, there has been a lot of hubbub over ivermectin for another reason. According to a number of ad-hoc groups across the world, as well as some scientific studies, ivermectin is a silver bullet against covid-19. And while there may be some question about whether ivermectin works, with the World Health Organization recommending that it only be used to treat covid-19 in the context of a clinical trial, there is also a lot of optimism about using it as a treatment. Half a dozen countries have officially promoted ivermectin as a drug for COVID-19, and it has likely been given to tens of millions of people across the world at this point, with prices skyrocketing as a result.

All of this is a bit worrying when you consider that we don’t really know if ivermectin works to treat covid-19, but it’s understandable given that more expensive treatments aren’t always available and people need something cheap that they can at least try for people dying of the infection. It’s not ideal, but there are some signs that ivermectin works, and it’s pretty safe, so why not give it a go?

Except for one thing. It appears that one of the pivotal, key trials of ivermectin in humans is full of holes – it was withdrawn late last week from the preprint server where it was hosted because of unspecified “ethical concerns”.

Upon close inspection, which has happened far too late, it’s hard to know if the study even happened. If that’s the case, it may mean that ivermectin has no benefit for covid and millions of people worldwide have been given a useless treatment.

Strap yourselves in, this is a very rough ride.

The study

Our problematic study, which I’ve written about before, is a preprinted paper published on Research Square by a group of doctors from Egypt. The study is titled “Efficacy and Safety of Ivermectin for Treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19 Pandemic”, and is quite impressive on face value, with the authors recruiting 400 people with covid and 200 close contacts and randomly allocating them to either get ivermectin or a placebo. Amazingly, the study found that people treated with ivermectin were 90% less likely to die than people who got the placebo, which if true would make ivermectin the most incredibly effective treatment ever to be discovered in modern medicine.

Moreover, as befitting the largest single randomised trial so far on ivermectin for covid-19, it has an outsized impact on the literature. As I’ve shown before, excluding just this single piece of research from various meta-analytic models almost entirely reverses their results. It’s not an exaggeration to say that this one piece of research is driving almost all of the benefit that people currently attribute to ivermectin.

However, even at first glance there are some problems. The authors used the wrong statistical tests for some of their results — for technical people, they report chi-squared values for continuous numeric data — and their methodology is filled with holes. They don’t report any allocation concealment, there are questions over whether there was an intention-to-treat protocol or people were shifted between groups, and the randomisation information is woefully inadequate. As a study, it looks very likely to be biased, making the results quite hard to trust.

But that’s perhaps not surprising, given that it’s possible the study never even happened.

Data discrepancies

The issues with the paper start at the protocol, but they certainly don’t end there. In what is a truly spectacular story, a British Masters student called Jack Lawrence was reading this article and noticed something odd — the entire introduction appears to be plagiarised. Indeed, it’s very easy to confirm this — I copy+pasted a few phrases from different paragraphs into Google and it is immediately apparent that most of the introduction has been lifted from elsewhere online without attribution or acknowledgement.

We could, perhaps, forgive some plagiarism in a preprint if it did truly find a miracle cure, but there are worse problems in the text.

For example, there are numbers that are incredibly unlikely, verging on impossible. In table 4, the study shows mean, standard deviation, and ranges for recovery time in patients within the study. The issue is that with a reported range of 9–25 days, a mean of 18 and a standard deviation of 8 there are very few configurations of numbers that would leave you with this result. You can even calculate this yourself using the SPRITE tool developed by the clever fraud detectives James Heathers, Nick Brown, Jordan Anaya, and Tim Van Der Zee — to have a mean of 18 days consistent with the other values, the majority of the patients in this group would have to have stayed in the hospital for either 9 or 25 days exactly. Not impossible, but so odd that it raises very serious questions about the results of the trial itself.

Somehow, it gets even worse. It turns out that the authors uploaded the actual data they used for the study onto an online repository. While the data is locked, our hero Jack managed to guess the password to the file — 1234 — and get access to the anonymous patient-level information that the authors used to put this paper together.

The data file is still online, and you can download it for $9 (+tax) US to peruse yourself. I’ve got a copy, and it’s amazing how obvious the flaws are even at a casual glance. For example, the study reports getting ethical approval and beginning on the 8th of June, 2020, but in the data file uploaded by the authors onto the website of the preprint fully 1/3 of the people who died from covid-19 were already dead when the researchers started to recruit their patients. Unless they were getting dead people to consent to participate in the trial, that’s not really possible.

Moreover, about 25% of the entire group of patients who were recruited for this supposedly prospective randomised trial appear to have been hospitalised before the study even started, which is at best a mind-boggling breach of ethics.

Even worse, if you look at the values for different patients, it appears that most of group 4 are simply clones of each other, with the same or largely similar initials, comorbidities, lymphocyte scores, etc.

Repeating segments (with minor changes) in the data are found in numerous scientific works that have later been proven fraudulent. But if it’s not fraud, the ethical concerns of randomising people into a clinical trial before the ethical approval comes through are still enormous.

I’m not going to go into all the discrepancies that this data shows. Both Jack Lawrence and Nick Brown have looked into the issues carefully, and I strongly recommend you read both of their pieces before continuing. They explain, in minute detail, all of the reasons why it appears quite unlikely that this study could have taken place as described.

I’ll give you a minute to read those. Trust me, it’s worth it.

Ok, we’re back. So, the authors have uploaded a dataset for their study that is very similar to the results they posted, but also quite obviously fake. What does that mean?

Well, it is possible that this is some huge error. Perhaps the authors created a spreadsheet that matched their study quite closely that was also made of simulated information for some unknown reason, and then accidentally uploaded that instead of the real information. Maybe when they put the file online they somehow managed to copy-paste a dozen patients 5 times, overwriting the real values in their haste to get their study up.

Perhaps. It does seem quite unlikely, especially given how closely most of the information in this spreadsheet matches the purported results of the study, but it is possible that this was a mistake made by otherwise trustworthy researchers.

The alternative prospect is that parts of or even the entire study is fabricated.

Consequences

This study has been viewed and downloaded more than 100,000 times, and according to Google Scholar has already racked up 30 citations since November 2020 when it was first posted. That means it has been used to drive treatment to patients, probably quite a few people at this point.

But it gets worse. Quite a lot worse, in fact.

You see, much of the hubbub around ivermectin is not due to this individual study, but as I said earlier because of meta-analyses. Two recent studies in particular have garnered a lot of attention, with both claiming to show that ivermectin is a life-saver with the highest quality of evidence.

The problem is, if you look at those large, aggregate models, and remove just this single study, ivermectin loses almost all of its purported benefit. Take the recent meta-analysis by Bryant et al. that has been all over the news — they found a 62% reduction in risk of death for people who were treated with ivermectin compared to controls when combining randomised trials.

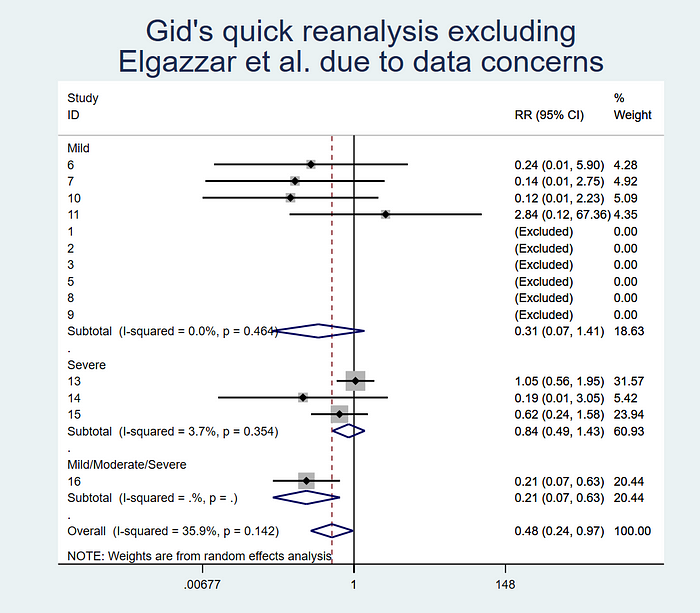

If you remove the Elgazzar paper from their model, and rerun it, the benefit goes from 62% to 52%, and largely loses its statistical significance. There’s no benefit seen whatsoever for people who have severe covid-19, and the confidence intervals for people with mild and moderate disease become extremely wide.

Moreover, if you include another study that was published after the Bryant meta-analysis came out, which found no benefit for ivermectin on death, the benefits seen in the model entirely disappear. For another recent meta-analysis, simply excluding Elgazzar is enough to remove the positive effect entirely.

This is a huge deal. It means that if this study is unsound it has massive implications not just for people who’ve relied on it but on every piece of research that has included the paper in their analysis. Until there is a reasonable explanation for the numerous discrepancies in the data, not to mention the implausible numbers reported in the study, any analysis that includes these results should be considered suspect. Given that this is currently the largest randomised trial of ivermectin for covid-19, and most analyses so far have included it, that is a really worrying situation for the literature as a whole.

Bottom line

The troubling reality is that enormous numbers of people have been treated with ivermectin largely based on a trial that, at best, is so flawed that it should never have been used for any treatment decisions. Even if we ignore the fake data uploaded with the study, it is hard to walk past the innumerable other issues that the research has.

Where does that leave us on the question of whether ivermectin works for covid-19? There are still one or two small, very positive trials, but in general ivermectin does not appear to reduce your risk of death.

Now, there are much larger trials ongoing to answer this question with certainty, and I eagerly await their results — as I’ve said before, the main problem right now is that the evidence simply isn’t good enough to be sure either way.

We are also left with a monumental reckoning. It should not take a Masters student/investigative journalist looking at a study to spot all its glaring problems. This study was reviewed by dozens of scientists including myself, and while I said it was extremely low quality even I didn’t notice the issues with the data.

It has been more than six months since this study was put online. And yet until now no one noticed that most of the introduction is plagiarised?

The scientific community, we noble defenders of truth, have well and truly cocked it up.

There’s no nice, easy ending for me to close on here. The investigation about this study is ongoing, and one day maybe we’ll have the story in its totality, but in the meantime the damage has been done. The horse has not only bolted, but lived a long and full life in the fields, and its descendants are taking steaming dumps on the broken wasteland where there once was a barn.

The scientific enterprise likes to ride high on the idea that science is “self-correcting” — that faults, mistakes, and errors are found out through the process of science itself. But this wasn’t a mistake. Credentialled experts read this trial and rated it as having a LOW risk of bias. Not once, but over and over again. Doctors looked at it and saw a miracle cure despite the endless issues that the research has even at fact value.

We will have to reckon with the fact that a truly woeful piece of research was put online and used to drive treatment to millions of people around the world.

And no one noticed until it was far, far too late.

This piece, and those linked, generated some heat online, to which the author responded:

So, @Covid19Critical does not agree with me, and says that the conclusions of meta-analyses do not change at all once excluding the retracted ivermectin study

— Health Nerd (@GidMK) July 17, 2021

Let's go over exactly why I said that removing the study makes a huge difference 1/n https://t.co/XULlZFzVFk pic.twitter.com/aMcvZ4PAnh

Note: Because I know people will say silly things, I have never been paid by any pharmaceutical companies, hold no interests in drugs of any kind, and am funded entirely by the Australian state and federal governments, as well as a bit of money that I get from locking my stories on Medium for you all to read. I have no financial interests in any covid-19 drugs, and honestly would love it if ivermectin cured the disease because then the pandemic would be over — I could go back to writing about whether chili peppers can stop heart attacks and that’d be much more fun.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz is an epidemiologist who tweets @GidMK

This piece was originally published at Medium