This potentially severe condition is underdiagnosed, writes a specialist in transcatheter aortic valve implementation.

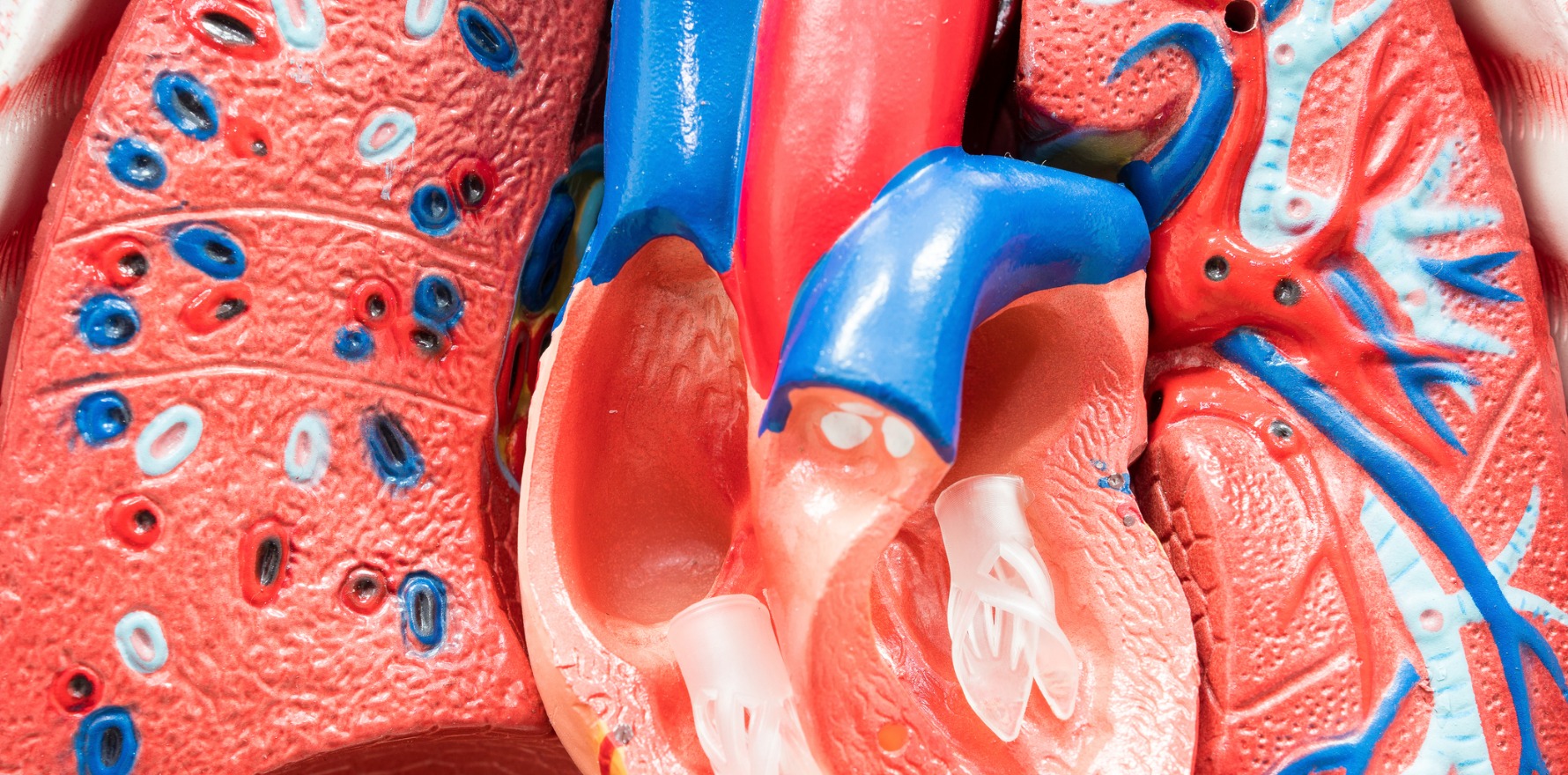

Aortic stenosis is one of the most common and serious forms of valve diseases requiring intervention.1

It is the abnormal narrowing of the aortic valve area, predominantly caused by calcification of the aortic valve.1

The prevalence of AS is associated with an ageing population, and is increased in patients aged 75 years and over.2 An estimated one in eight elderly Australians is diagnosed with AS.2

The disease course of AS is characterised by a long latency period in which patients are asymptomatic, followed by more rapid progression and poor prognosis upon symptom onset.3 This latter period is symptomatic severe AS.

It is important for patients living with symptomatic severe AS to have intervention, because those who do not have a high mortality rate. Approximately 50% will die within an average of two years of symptom onset.3

Public awareness of AS symptoms and their significance is low. International surveys of people over 60 years of age have reported that while one in five patients were aware of AS, only 3.8% to 7% of respondents could correctly identify the condition.4

Helping patients and the public to understand severe AS symptoms – including who is at high risk of developing severe AS, and the gravity of clinical outcomes – is important to raising awareness of this condition.5

The symptomatology of symptomatic severe AS includes the following, particularly upon exertion:1,6

- Dyspnoea or fatigue

- Syncope / dizziness

- Angina / chest pain

Identifying AS in elderly patients can be a difficult process. Exertional fatigue may often be viewed as a normal component of ageing, rather than an underlying part of cardiac dysfunction. Similarly, dizziness can fall under multiple unrelated diagnoses.6

Diagnosing AS early and evaluating disease progression and timing of intervention are therefore imperative. General practitioners can take a role in educating and monitoring patients for the signs of severe AS, and ensuring those patients are referred for diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

When it comes to evaluating patients for AS, the European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2017 guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease provides valuable direction.7

Establishing a diagnosis of AS begins with the following key components of patient evaluation:7

- Patient history

- Symptomatic status

- Physical examination including auscultation

- Comorbidities and general condition should also be considered

For patients in whom AS is suspected, echocardiography is the key diagnostic tool to determining the presence and severity of AS. The ESC guidelines also recommend consideration of exercise testing in physically active patients to unmask symptoms if suspected, but the clinical history is ambiguous.7

Recommendations from a focused update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography identifies three primary haemodynamic parameters for the diagnosis of AS:8

- Velocity/flow rate

- Mean transvalvular pressure gradient

- Aortic valve area

Additional factors to consider are ventricular function, wall thickness, and the degree of valve calcification. Echocardiographic parameters and signs of symptoms should be re-evaluated regularly in patients with asymptomatic severe AS.7

While not a part of the guidelines, patient education after diagnosis remains important, especially with regard to symptom status and what that encompasses for their prognosis. For asymptomatic patients, a particular focus can be placed on symptom awareness.

Patients with symptomatic severe AS should be aware that while no medical therapy currently exists to improve their outcome, there are interventions available.7

The only effective intervention available for symptomatic severe AS is aortic valve replacement.7 This involves replacement of the diseased aortic valve with a tissue or mechanical valve. After evaluating an AS patient, the heart team will choose the most suitable procedure. Patients may undergo surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), commonly known as open heart surgery, or transcatheter aortic valve implementation (TAVI).

Despite the availability of effective intervention options, AS patients may still not be adequately treated. Studies show that, historically, at least 40% of patients with severe aortic stenosis did not receive treatment.9–11

A series of paradigm shifts in the past decade have shown that TAVI is an effective intervention for symptomatic severe AS patients at all strata of baseline surgical risk, including patients who could only previously receive SAVR.12–15 This has substantially expanded the treatment options available to heart teams, and means they can now consider TAVI for their symptomatic severe AS patients independent of surgical risk.

The most recent and significant development for TAVI in Australia is the extension of the eligibility of the procedure to symptomatic severe AS patients with a low surgical risk score. Indeed, it is estimated that 79.1% of patients with severe AS symptoms are at low risk of surgery.

The approval therefore significantly increases access to the procedure.15 This approval is based on data from the landmark PARTNER 3 trial, an independently evaluated, randomised controlled trial comparing outcomes between TAVI and SAVR.15 TAVI with the SAPIEN 3 system achieved superiority over SAVR, with a 46% reduction in the event rate for the primary endpoint of the trial, which was a composite of all-cause mortality, all stroke and rehospitalisation at one year.15

In low to intermediate risk AS patients, additional studies found TAVI reduced the risk of life threatening or disabling bleeding and the new onset of atrial fibrillation within two years of the procedure versus SAVR.16 These results speak to the future of TAVI for AS patients.

The key points to raise awareness for severe AS are:

- Educate patients about the symptoms and outcomes of severe AS

- Know the diagnostic pathway

- Keep up to date on the latest aortic valve replacement research.

Dr Ronen Gurvitch is a general and interventional cardiologist and TAVI specialist based in Melbourne.

References:

- Baumgartner H and Walther T. Chapter 35.3 Aortic Stenosis. ESC CardioMed (3rd edition). Available online at https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780198784906.001.0001/med-9780198784906-chapter-766 (Accessed August 2020)

- Osnabrugge RLJ et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(11): 1002–12.

- Ross J Jr and Braunwald E. Circulation 1968; 38: 61–7.

- Gaede L et al. Clin Res Cardiol 2019; 108(1):61–7.

- Guerbaii RA et al. PLoS One 2017; 12(6): e0178932.

- Everett RJ et al. Heart 2018; 104: 2067–76.

- Baumgartner H et al. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2739–91.

- Baumgartner H et al. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 18(3): 254–275.

- Bach DS et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009; 2(6): 533–9.

- Freed BH et al. Am J Cardiol 2010; 105(9): 1339–42.

- Leon MB et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607.

- Smith CR et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187-2198.

- Mack MJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-705.

- Vandvick PO et al. BMJ2016;354:i5085.