A guide for GPs to the short and long-term management of acute coronary syndromes

While the majority of patients presenting to a GP with chest pain will not have a life-threatening condition, a significant minority will be experiencing an acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

In Australia, 68,200 ACS events were recorded in 2012.1 There is strong evidence that delay in diagnosis and management of acute coronary syndrome leads to poor prognosis and avoidable complications2, including heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, mechanical complications and sudden cardiac death3, therefore early recognition and management is essential.

In this article, we present a case report of a patient presenting to their general practitioner with chest pain, including a discussion of the differential diagnosis, risk stratification, and current management guidelines for acute coronary syndromes.

Case Study

A 49-year-old accountant presents to his general practitioner with epigastric pain, nausea and diaphoresis, which has progressed over the previous 90 minutes at work. He has no history of syncope, palpitations or dyspnoea, however in recent weeks has noticed declining exercise tolerance when playing competitive football with his local over-45 football team, which he has attributed to suboptimal fitness.

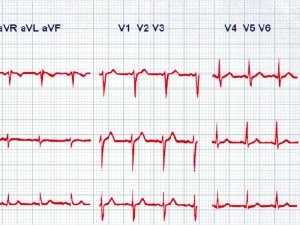

On examination, he appears unwell, with pallor and diaphoresis. His heart rate is 78b/m, blood pressure 138/83 mmHg, oxygen saturation 98% on room air and temperature 36.3C. Physical examination reveals no features consistent with congestive cardiac failure, and his abdomen is soft and non-tender. His GP arranges for an ambulance to be called urgently and performs an ECG (See Figure 1 on page 40).

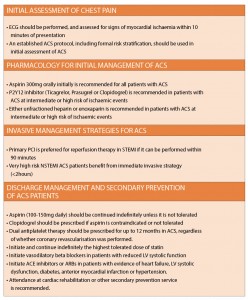

Assessment of acute chest pain

Any individual with acute chest pain requires careful history and physical examination, urgent investigation and referral to the emergency room, or often in cases of acute coronary syndrome, directly to the cardiac catheter lab for coronary angioplasty and stenting.

An ECG should be performed urgently if possible. If it’s abnormal, or there is a high clinical suspicion of serious pathology, early referral to hospital is indicated for further investigations, including as clinically indicated, serial cardiac troponin for non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes, D-Dimer, chest X-ray and CTPA to identify acute pulmonary embolism4 or CT aortogram to identify aortic dissection.5

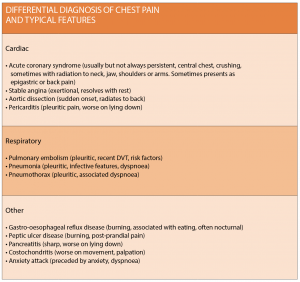

(Common differential diagnoses are shown in table 1 at right).

Risk stratification

Patients with ST elevation on ECG are suffering transmural myocardial necrosis due to occlusion of a coronary artery. They require immediate activation of strategies to open the occluded vessel. Risk stratification of patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes guides investigation and management to avoid

poor outcomes.

Patients with a high risk require early invasive investigation and treatment.

GRACE (the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) is an international observational program of outcomes for patients hospitalised with an ACS in the 10 years from 1999. The data was used to develop the GRACE score (www.gracescore.org). The GRACE score, based on parameters of age, heart rate, systolic BP, creatinine level, cardiac arrest at presentation, ST segment changes on ECG, troponin elevation and heart failure, is a widely utilised prognostic indicator in NSTEACS3.

Back to the case:

The ECG reveals anterior STEMI, and an ambulance is called for immediate transfer to hospital. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate and 300mg of aspirin is administered.

Upon arrival to hospital, the patient’s heart rate is 100b/m and blood pressure is now 95/70mmHg.

Initial bloods demonstrate a normal full blood count and biochemistry (creatinine 75 mcmol/L), and first troponin of 45 ng/L (mildly elevated). His chest X-ray is clear.

The coronary catheterisation lab is activated for an immediate angiogram and percutaneous coronary intervention.

On route to the catheterisation lab, the patient receives an intravenous heparin 5000IU bolus, is commenced on an intravenous heparin infusion and intravenous tirofiban (a glycoprotein IIbIIIa inhibitor, which is a potent antiplatelet agent).

A trans-thoracic echocardiogram is performed on the cath lab table, which reveals moderate systolic LV impairment due to anteroapical akinesis. Coronary angiography reveals complete occlusion of the left anterior descending artery, and a drug-eluting stent is urgently inserted into this artery.

Post procedure, the patient is commenced on dual antiplatelet therapy (prasugrel plus aspirin), which he is instructed to continue for a minimum of 12 months. He is also commenced on a beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor and a high-dose statin (even without documentation of his lipid profile). The troponin level peaks at 1800ng/L.

He has no signs of heart failure. He tolerates his medical therapy well and is discharged four days after presentation.

ACS Management

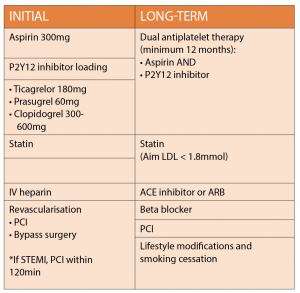

If ACS is suspected, the recent acute coronary syndrome guidelines2 suggest that in addition to aspirin 300mg, a P2Y12 inhibitor (ticagrelor 180 mg orally, followed by 90mg twice a day or; prasugrel 60mg orally, followed by 10mg daily;

or clopidogrel 300 to 600mg orally, followed by 75mg per day) should be administered.

Parenteral anticoagulation, most commonly with IV heparin, should be used additionally prior to coronary intervention. High-risk ACS patients may also receive glycoprotein IIbIIIa inhibition. In most tertiary and metropolitan hospitals, and larger rural centres with a cardiac cath lab, the artery is opened by coronary angioplasty and stenting.

In smaller rural or metropolitan hospitals where delay in transfer to a centre with primary angioplasty facilities is unavoidable, patients with ST elevation ACS receive thrombolytic agents before transfer for comprehensive cardiac assessment and management.

Ideally, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) should be performed within 120 minutes of first medical contact or with a door to balloon time (arrival to ED until artery is opened with angioplasty) of 90 minutes in a PPCI centre.

After six weeks our patient is active and well, back to work, with follow-up echo confirming normalisation of LV systolic function. He has participated in his local cardiac rehabilitation program. He understands the importance of complying with his medical regimen including the risk of stent thrombosis if he ceases his dual antiplatelet therapy early. He is advised to avoid competitive sport including football at least for the remainder of this season.

Dual antiplatelet therapy should be continued for 12 months, with subsequent antiplatelet therapy determined by balancing the benefit of antiplatelet therapy and bleeding risks. Lipid lowering and plaque stabilisation with statins is fundamental in reducing the risk of recurrent cardiac events and mortality.

An LDL cholesterol level ?1.8 mmol/L should be achieved with high-dose statin therapy. The use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is strongly recommended in individuals with left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, diabetes and concomitant hypertension. Similarly, beta blockers play a key role in individuals with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure. The goal should be to up-titrate these agents to the maximum tolerated doses based on blood pressure and heart rate (See table 2, top left).

Daniel Ishak, BMed MD, is basic physician trainee at Sutherland and St George Hospital.

Vinayak Nagaraja, MBBS MS, is a advanced trainee in cardiology trainee at Sutherland, St George and Prince of Wales hospital network.

Shiva Roy, MBBS FRACP FCSANZ DDU, is senior staff specialist in cardiology, Sutherland Hospital

References:

1. Australian institute of Health and welfare 2014, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Australian facts: Prevalence and Incidence

2. Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. Heart Lung Circ 2016;25:895-951.

3. Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2345-53.

4. Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:589-602.

5. Suzuki T, Distante A, Zizza A, et al. Diagnosis of acute aortic dissection by D-dimer: the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection Substudy on Biomarkers (IRAD-Bio) experience. Circulation 2009;119:2702-7.