Aesthetic medicine is a runaway business full of conflicts of interest. Can AHPRA stop its race to the bottom?

In September AHPRA announced its (mostly expected) decision to continue reforms into the largely unregulated field of aesthetic medicine by targeting non-surgical procedures, having already looked at cosmetic surgery reforms in July.

The bar for medical aesthetics is far lower than for surgery since the field is open to nurses, doctors and dentists soon after graduation; the price point for entry for consumers is also much lower in the non-invasive aesthetic space than in cosmetic surgery, so competition first and foremost on price is common. Hence the greater hidden potential for harm.

Disillusioned nurses and doctors as well as FRACGPs are flocking to aesthetic medicine in ever increasing numbers thanks to savvy marketing and recruitment that capitalises on this.

Training for injectors involves as little as a one or two-day “bootcamp” or a week’s training. Thereafter they are free to set up on their own, working independently out of salons, hairdressing premises and laser clinics in shopping centres. Many chains also have doctors who script for a vast number of nurses, many of whom they may have never met, and who may be interstate.

Social media groups are regularly flooded by new graduate nurses, many of whom undertook nursing purely to get into aesthetics. Many junior doctors, post the mandated internship, are also bypassing speciality training to get into aesthetics.

Lastly, FRACGPs are routinely asking about ways to incorporate aesthetics into their work, or hiring a nurse to inject patients in their clinics on a weekly basis.

As Dr Ronald Feiner told TMR last month, it is unheard of in any other field of medicine for registered nurses to work independently of doctors, or indeed, for any other healthcare professionals to work the way medical aesthetics seems to be set up – but this could have been foreseen years ago when the medical aesthetics boom occurred.

Unlike most other specialties which require years of oversight and supervision to ensure competency and safety for patients, medical aesthetics, driven largely by the companies selling the drugs as products, is an untested field that seems to have slipped through the cracks. Drugs are sold and bought directly by not only doctors who can prescribe them, but also stored by independent nurses, delivered by the companies.

Until July, the video consultation process to consent a patient by a doctor many kilometres away, if not interstate, was a quick “Hi, hello, do you understand what you are having?” following by scripting a dose for the nurse to inject, which was valid for a full year.

Equally worrying for me, is the marketing that glamorises medical aesthetics and targets ever younger markets with terms such as “preventive anti-wrinkle” treatment – with taglines such as “The best wrinkle is the one you never have” – to lure unsuspecting young people into treatments they don’t need at significant cost.

It’s no wonder then, that, as with Painkiller, we have created a perfect storm whereby direct marketing has taught patients to order treatments by dose (“I’ll have 20 units of X”; “how much for 0.5ml lip filler?”). The healthcare worker seeing them, usually at a free consultation, is then conflicted. Say no, you waste 15-30 minutes of a free consultation and lose the associated revenue; or say yes, because “the customer is always right”, and earn a decent buck, ethics be damned.

In what other area of medicine do we routinely have patients insisting on a specific drug and a specific dose that they’re willing to pay for, because they believe they are paying for the drug itself, not the treatment or outcome?

When I see a patient and diagnose a skin cancer and counsel them on its excision, I quote my fee based on the complexity of the procedure, my skillset, the time it’ll take me and consumables used. They are NOT paying for the amount of lignocaine I use, or the type of flap I will create.

Yet in most instances, we now have patients ordering doses of medications and healthcare workers offering packages of aesthetic treatments, much like one bulk-buys a sack of rice at Costco – “3 areas of anti wrinkle + 1ml premium dermal filler RRP $X …”.

The more you buy, the more everyone wins; the customer wins by scoring more filler and anti-wrinkle for less unit pricing. The injector wins by making more money by selling more. Whether the patient actually needed that package in the first place … ethics schmethics, shhhhh.

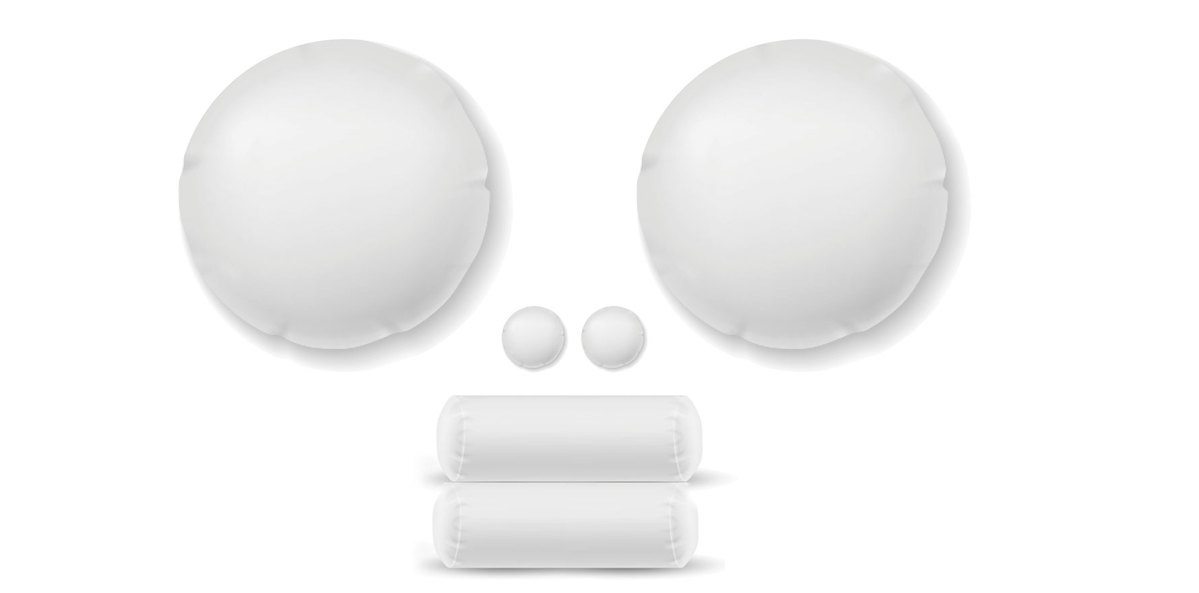

In turn, this leads to fierce competition based on price when more and more inexperienced injectors with bare minimum qualifications flood the market and can only compete on price. Having never learnt adequate boundaries, they say yes to whatever the “client” wants, leading not only to increased risk of serious complications, which become overrepresented in naive hands; equally, lack of adequate training and oversight risks the dreaded “pillowface” and its companion: complaints by patients who feel botched and ripped off after shopping based on the price being right.

Lastly, similar to doctors paid by the pharmaceutical companies to lend credibility to their products, the aesthetics world has KOLs (key opinion leaders) that speak for and represent certain companies, sometimes exclusively, and promote their devices in exchange for those devices being gifted to them; others do paid promotions for skincare companies and thereby increase revenue for these companies by way of their large social media followings.

Ultimately, there has been a chasm that has arisen between what we in medicine, at least, are taught about conflict of interest and what is now happening and accepted as normal; healthcare workers being paid to actively promote products and devices for companies without any declaration of the COI.

In any market where the doors are essentially opened to a large group with base qualifications for entry, this is a given, fed by the companies that currently remain mostly unregulated. This flood shows no sign of abating as more and more groups find a way into the market to qualify as injectors and the public remains blissfully unaware, seeing regulation as a form of gatekeeping.

No wonder, then, that AHPRA is turning its eye to this large cross section of the aesthetics industry. Whether any good will come of it remains to be seen; my feeling is that the horse has bolted.

Dr Imaan Joshi is a Sydney GP; she tweets @imaanjoshi.