You can play an important role in supporting patients through diagnosis and treatment, including reducing the stigma and shame surrounding the disorder.

How often have you heard people in society make comments such as “that’s so OCD” in relation to someone who is concerned with neatness or cleanliness?

Unfortunately, this colloquial use of terminology minimises the lived experience of those suffering from what is a highly debilitating disorder and involve much more than a general tendency towards neatness or a general concern about things being clean.

As health professionals, we can play an important role in reducing the stigma and shame surrounding obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and increasing the likelihood of patients speaking up about their symptoms, receiving an accurate diagnosis and accessing appropriate treatment.

What is OCD?

The DSM-5 1 classifies OCD as a mental health condition that is characterised by the following:

- Obsessions: intrusive, recurrent and unwanted thoughts, images, doubts, urges or worries that are distressing and uncontrollable. Obsessions can be incredibly graphic, horrifying and disturbing. Obsessions can induce emotional distress usually in the form of anxiety, but can also cause other emotions such as disgust, shame, horror and discomfort;

- Compulsions: repetitive actions that the individual feels driven to perform in response to the obsession, to either neutralise the obsession in some way or to alleviate the associated anxiety. Compulsions can either be overt behaviours (e.g., checking, hand washing) or mental acts (e.g., repeating a phrase in one’s head, replacing a ‘bad’ thought with a ‘good’ thought, scanning one’s body to check how it feels).

It is worth noting that it was previously believed that some individuals with OCD had only obsessions – a condition referred to as “purely obsessional” or “pure O” OCD. However, we now know that OCD always involves compulsions, but sometimes these are hidden mental rituals that cannot be easily identified or seen by outside observers.

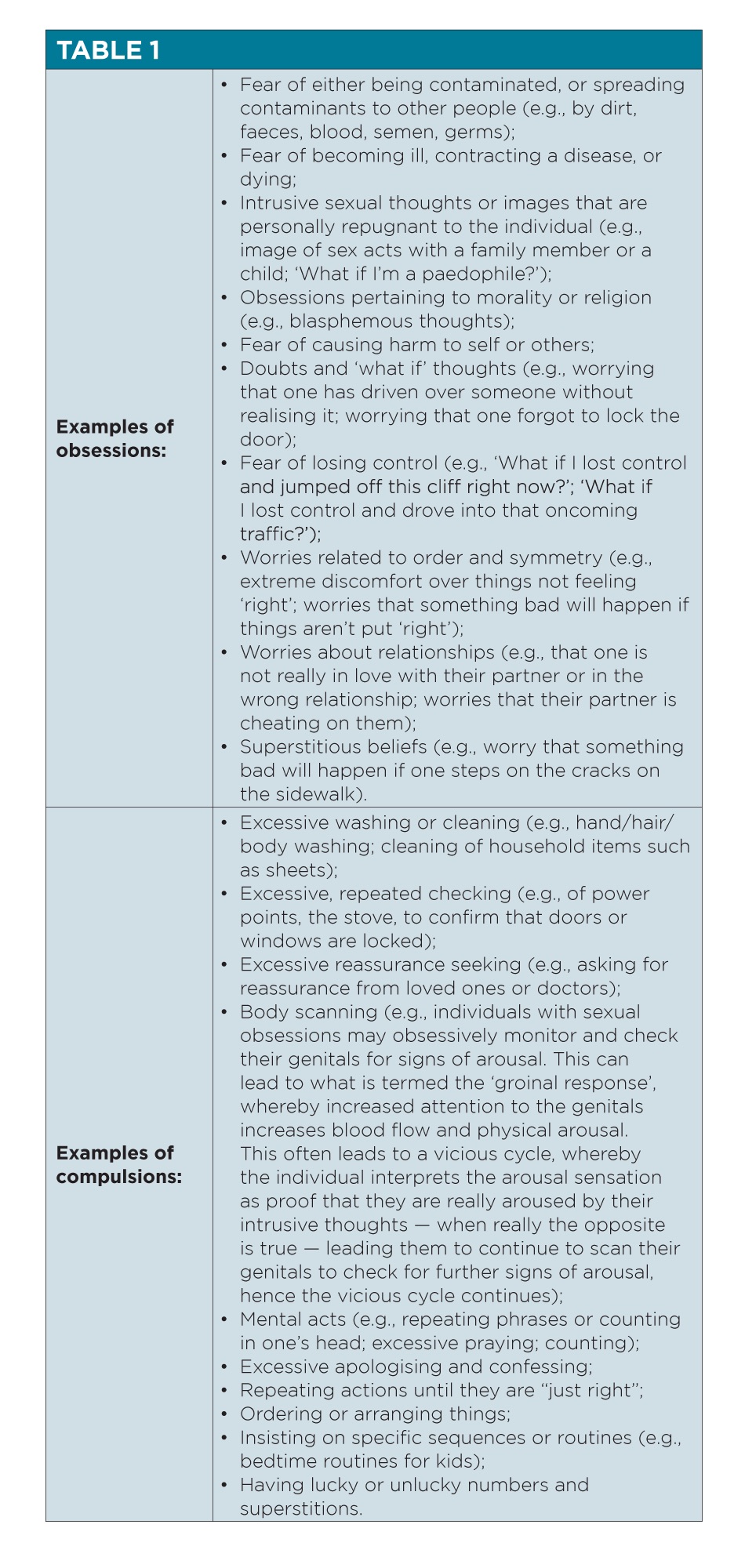

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for OCD, the obsessions and compulsions must be time consuming (taking at least one hour per day) and cause significant distress or impairment in functioning2 . See Table 1 for typical examples of obsessions and compulsions. However, keep in mind that this is by no means an exhaustive list; obsessions and compulsions can and do vary widely from individual to individual.

How common is OCD?

OCD is a common and often disabling mental disorder. About 2.8% of Australians will meet criteria for OCD in their lifetime3. The World Health Organisation4stipulates that anxiety disorders, which they categorise as including OCD, are the sixth-largest contributor of non-fatal health loss and are one of the top 10 causes of years lost to disability globally. OCD can present at any age, with the most common periods of onset between eight and 12 years of age and then in late teens through to early adulthood.

The good news is that when those with OCD access appropriate, evidence-based treatment, there is hope. Many experience significant improvements in symptoms and functioning5.

Unfortunately, there are various barriers to individuals with OCD disclosing their symptoms to healthcare professionals and accessing treatment, including that many sufferers of OCD experience intense feelings of shame about their symptoms5,6 . Indeed, the average delay of seeking treatment after initially developing OCD symptoms is 11 years7.

Detecting OCD

General practitioners are in a unique position to identify patients presenting with OCD and guide them to access appropriate support. OCD can be challenging to identify when patients are often apprehensive about openly discussing their symptoms due to shame and fear of judgment. Nonetheless, by providing a safe environment for disclosure through an empathetic approach, careful questioning and education about OCD, GPs can pave the way for the patient to engage in effective treatment.

From our clinical experience, while patients may not always initially disclose their OCD symptoms, they may talk more generally about struggling with “racing” or “bad” thoughts that are distressing or won’t go away. They often also discuss feeling out of control with various behaviours and routines that they are engaging in to manage their anxiety.

It may be necessary to probe further and ask a series of direct questions to screen for OCD. Sometimes patients may feel more comfortable completing a questionnaire than verbally discussing their symptoms. As such, GPs may also consider administering the YBOCS — a useful screening tool that lists common obsessions and compulsions8. Alternatively, they could use a list of screening questions such as:

- Do you ever have distressing, unwanted thoughts that keep coming back?

- Do you ever do anything — either in your head or a behaviour – in response to those thoughts to either stop the bad thing happening or to get rid of your anxiety?

- Do you feel you have to do specific routines and rituals every day?

- Do you ever feel you have to do things again and again, sometimes getting stuck and feeling like you can’t stop even if you want to?

For child patients, asking parents about a child’s behaviours to cope with anxiety and stress may provide an indication of potential OCD (see list of common compulsions in the above table). Child patients are likely to have increased fears about vocalising their obsessions due to fear that speaking them aloud may make them happen and therefore early identification through observed behavioural responses and signs of distress can often be easier and can facilitate appropriate referral options for further assessment.

Screening tools alone are not sufficient to make a formal diagnosis, so referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist for further assessment is likely to be warranted.

OCD shares some similarities with anxiety disorders and is often misdiagnosed. For example, the intrusive thoughts experienced by those with OCD can often resemble and easily be mistaken for the excessive, difficult-to-control worries featured in generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). Other similarities that are often featured in both OCD and GAD include intolerance of uncertainty and excessive reassurance seeking.

Misdiagnosis is problematic as OCD requires specialised treatment involving exposure and response prevention (ERP), which tends to not be included in interventions for anxiety disorders such as GAD. This means that patients with OCD can slip through the cracks and miss out on potentially life-changing psychological treatment. For this reason, it is crucial to refer patients suspected of having OCD to clinicians who are trained and experienced in treating OCD so they can distinguish between OCD and other conditions to achieve an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan.

Supporting individuals with OCD through education

Once you have identified that a patient may have OCD, what then?

Given a lot of OCD sufferers experience significant shame about their symptoms, it can be incredibly helpful to provide them with education about OCD that busts myths to assist them to feel comfortable accessing treatment. See below for example scripts of how you might respond to common concerns that patients may have about their condition.

- “Can I really have OCD? I don’t do any compulsions such as washing my hands … it’s all just in my head”

- “That’s a really good question and I’m so glad you asked. The truth is, while often when we hear about OCD and see it in the media as focusing on behaviours such as excessive cleaning and hand washing, OCD comes in many different forms. While some individuals with OCD have obsessions and compulsions related to cleanliness, many do not. Also, a lot of people with OCD don’t have behavioural compulsions, they do their compulsions in their head (e.g., replacing a ‘bad’ thought with a ‘good’ thought).”

- “Why can’t I just stop it?!”

- “If it was that easy, you would have just stopped by now, right? This has nothing to do with willpower and this is not your fault. The nature of OCD is that it keeps you stuck in a vicious cycle of obsessions, anxiety and compulsions. However, I have good news for you — you are not alone. There are many people with OCD and there are effective, evidence-based treatment options that have helped a lot of people to recover. Can I tell you about these options now?”

- (For individuals with compulsions related to harm or paedophilia): “What if I really am dangerous? What if these thoughts mean I actually want to do these things or that I’ll lose control and do it?”

- “Remember — these are just thoughts. People with OCD are just as unlikely to act on their thoughts as anyone else in the population.

- “Actually, research has shown that everyone has random intrusive thoughts about the same sorts of things as people with OCD (Radomsky et al., 2014). The only difference is that rather than dismissing the thoughts as rubbish, which is what they are, individuals with OCD interpret them as being a threat. For example, someone without OCD might have the thought ‘imagine if I just drove my car into that oncoming traffic’. They would probably just dismiss it as a silly, irrelevant thought, knowing that of course they would never act on that thought. However, an individual with OCD will interpret that thought as being important, significant and dangerous (e.g., ‘Why did I have that thought? This must mean I’m really a violent, dangerous person deep down. Does this mean I’m going to do it?’). This of course leads to a spike in anxiety, and the individual will engage in compulsions to alleviate the anxiety. The problem is, although engaging in compulsions leads to an initial reduction in distress, it maintains anxiety over time, hence the vicious cycle of OCD continues.

- “Obsessions are not a reflection of an individual’s personality or desires. In fact, OCD obsessions tend to target the things that people value and care about the most, making this disorder particularly cruel (e.g., a loving mother might have obsessions centred on fears that she will harm her baby; an individual whose religion means a lot to them might have obsessions related to fear that they are really a blasphemer who hates God deep down).”

It can also be helpful to be aware of the role that reassurance seeking plays in maintaining OCD as patients with OCD often engage in excessive reassurance seeking as a form of compulsive behaviour. For example, a patient may repeatedly ask for your reassurance that the same physical symptoms are not indicative of a serious disease or that they haven’t been exposed to an illicit or dangerous substance. As a caring practitioner, it is of course tempting to alleviate the patient’s anxiety and provide this reassurance. However, reassurance is just another compulsion that serves to perpetuate anxiety and OCD over time.

If you notice that your patient with OCD is asking for a lot of reassurance, it is recommended that you point this out in a compassionate way. You might, for example, normalise that excessive reassurance seeking is common among individuals with OCD and explain how although it reduces anxiety in the short term, this relief is short lived and like all compulsions it keeps their anxiety going over time. You might also explain that a crucial component of OCD is learning to tolerate uncertainty and sit with doubt and that you would like to support them in this process.

It can be helpful to involve patients in collaboratively making an agreement about how to manage reassurance seeking. This could look like setting guidelines about how often or when to come for a consult, or making an agreement that you will gently identify when you notice that they are engaging in excessive reassurance seeking in the future (e.g., if they ask for reassurance about something you have already explained).

Treatment guidelines

Once a patient has been diagnosed with OCD and is willing to engage in treatment, GPs play an instrumental role in supporting their recovery journey, both as a prescribing practitioner and in referring to appropriate psychological treatment services.

Treatment guidelines stipulate that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) incorporating ERP and certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) either standalone or in combination are the first-line treatment recommendations for OCD9,10.

High doses of SSRIs are required to achieve beneficial outcomes in OCD, beyond the dose recommendations outlined in the prescribing information, which is usually based on clinical studies for depression, with the full effect of the medication likely to take up to 12 weeks to occur11.

For OCD, daily doses of up to the following for the listed medications is usually required: 80mg of fluoxetine; 300mg of fluvoxamine; 60mg of paroxetine; 40mg of escitalopram; 80mg of citalopram; 250mg of clomipramine and 200mg of sertraline. Occasionally even higher doses may be needed for optimal benefits12. Anecdotally, our experience is that a good indicator of whether medication for OCD symptoms is helping is whether the patient reports that their thoughts are “quieter”.

When referring for psychological treatment, it is crucial to check that the therapist is trained and experienced in ERP. Treatment for OCD is very specific and differs from the treatment of anxiety disorders. ERP involves supporting the patient to create a hierarchy of situations that trigger their OCD obsessions and anxiety, rating them from least to most anxiety provoking.

The therapist then supports the patient to expose themselves to these situations with the goal of staying in the situation without engaging in their compulsions until their anxiety reduces on its own and new learning occurs (i.e., that the thought is just a thought, and is not dangerous). These exposures are repeated until the patient habituates to each situation, at which point they move on to the next step in the hierarchy. For patients to achieve significant improvement in symptoms, ERP usually requires up to approximately 20 sessions, but this can vary widely between patients and for more complex and severe cases treatment can take significantly longer than this.

Dr Amy Talbot is a clinical psychologist with a special interest in OCD and OCD-related presentations. She is the clinical director at the Talbot Centre, a private outpatient service with a team of clinicians who provide assessment, diagnosis and intervention for OCD onsite in north-west Sydney and nationwide via telehealth platforms.

Imogen O’Loughlin is a clinical psychologist with a special interest in OCD and related presentations who works at the Talbot Centre in north-west Sydney. Imogen is passionate about supporting her clients with OCD to overcome and become free of the vicious cycle of distressing intrusive thoughts and compulsions/rituals.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013a). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results. ttps://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-survey-mental-health-and-wellbeing-summary-results/latest-release

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf;jsessionid=6B2EA1DDE9BAEF718BB8B945B255C60C?sequence=1

- Law C, Boisseau C (2019). Exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 1167-1174. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S211117

- Fenske J, Petersen K (2015) Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Diagnosis and Management. American Family Physician, 92(10), 896-903.

- Glazier K, Wetterneck C, Singh S, Williams M (2015). Stigma and shame as barriers to treatment for obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 4(3), 1-5. doi:10.4191/2167-1044.1000191

- Pinto A, Mancebo M, Eisen J, Pagano M, Rasmussen S (2006). The brown longitudinal obsessive compulsive study: Clinical features and symptoms of the sample at intake. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(5), 703-711. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0503

- Goodman W, Price L, Rasmussen S, Mazure C, Fleischmann R, Hill C, Heninger G, Charney D (1989). The Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-1011. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2005). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: treatment clinical guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG31/chapter/1-Guidance#steps-35-treatment-options-for-people-with-ocd-or-bdd

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013b). Guideline watch (march 2013): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Bloch M, McGuire J, Landeros-Weisenberger, A, Leckman J, Pittenger, C (2009). Meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship of SSRI in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(8), 850-855. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.50

- American Psychiatric Association. (2007). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.