Digital mental health services are not the “solutions” they claim to be. They lack data, GPs find them useful in only a few patients, and most patients don’t want them.

Hans Christian Anderson’s The Emperor’s New Clothes is a fairytale about two conmen who pretended to be weavers. They convinced the Emperor they have a magical fabric with which they could make him the finest suit in all the land. Only intelligent and brave people can see the fabric, they say, and anyone who can’t see it is stupid and incompetent.

The Emperor is vain, and this is the crux of the con. He loves fine clothes, and he sees himself as intelligent. Like everyone else, he pretends to see the cloth the conmen pretend to weave, as he doesn’t want to be known as stupid and incompetent. Eventually, he wears the imaginary “clothing” the conmen create in a parade but the spectators fear looking stupid or incompetent, so they all comment on how magnificent he looks.

Finally, a child yells out “the Emperor isn’t wearing any clothes” giving everyone permission to admit the Emperor is naked. The Emperor, of course, is forced to confront his own stupidity and ignorance.

Speaking out when the emperor is naked: the problem of digital mental health

The magic fabric in our world is evidence. Or the lack of it.

One of the main problems we have in healthcare today is the lies we tell ourselves, as well as the lies that are told by others, so I thought I would take a moment to take a piece of what I believe to be poor policy and be the little kid in the crowd pointing out that the Emperor is not wearing any clothes.

In this story, let’s look at the National Digital Mental Health Framework, which is not wearing much data.

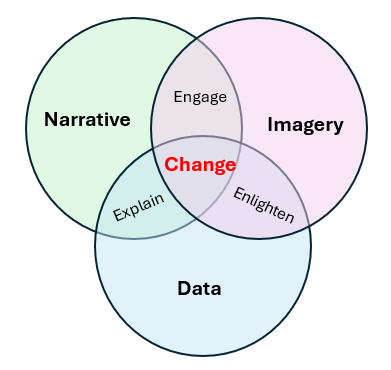

Data stories are usually made of three things: data, a narrative and good imagery. Over time, I’ve watched data stories rely on less and less data. Sometimes, like this policy, they make a token attempt at data, a little like putting a sticker on lollies and calling them “all natural” or labelling a sugar-dense food as “lite”.

Without data, the framework tries to engage us without explaining why.

The data story

The National Digital Health Framework tries to tell us that:

“Digital Health has the potential to help people overcome healthcare challenges such as equitable access, chronic disease management and prevention and the increasing costs of healthcare. By enhancing the use of digital technologies and data, it enables informed decision-making, providing people better access to their health information when and where they need it, improved quality of care, and personalised health outcomes.”

Governments would love this to be true. More public services are moving to digital means of access. And yet it seems the digital divide is a new social determinant of health. The poorer you are, the less access you have to digital goods, and as more and more services are now delivered online, the greater your disadvantage becomes.

Digital mental health services give the illusion of universal access, but let’s look at how they are used in practice.

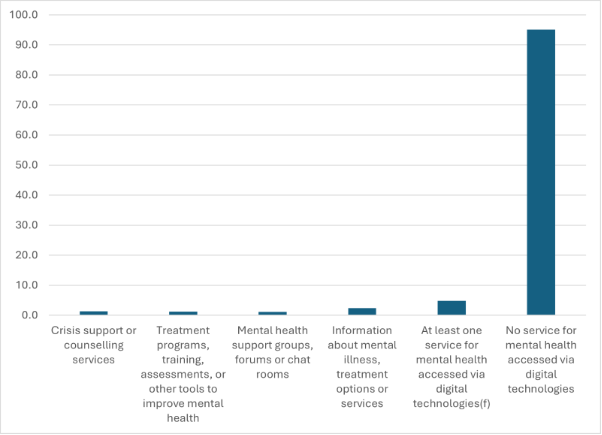

The first thing to say is that they are used rarely. Despite the massive investment in digital tools, the people are “voting with their feet” and avoiding them. Here’s the data from the National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2020-2022.

Proportion of people aged 16-85 years with a history of mental health disorders (with and without symptoms) accessing digital technologies.

In most environments, this would be interpreted as consumers making a choice. In this environment, it is cast as a problem of GP motivation. GPs, apparently, are the problem, because we don’t know how to use digital mental health tools, or we don’t know they exist. Apparently, this means we need nudging to overcome our “reluctance”.

The digital health strategy tells us we need to be nudged to overcome our “reluctance”.

“Investments into research, education and awareness promotion, evidence translation, resources and tools contribute to building trust in the efficacy and effectiveness of digital mental health services for stakeholders.”

So maybe GPs just need to become familiar with the evidence and stop “stalling digital mental health”. The scoping review prior to the release of the National Digital Mental Health Framework has an explicit reference to this:

“What are possible financial and non-financial incentives (professional standards, training, monetary incentives) to encourage health practitioners to adopt digital mental health services into ‘business as usual’?”

In other words, make it compulsory.

At the moment, the PHNs are required to use a common assessment tool, which despite over $34 million in investment, has no validity or reliability measures, to place people into five levels. At level one and two, digital mental health strategies are the preferred solution to their needs. If I were psychic, I would predict that when GPs are “required” to use the tool, no-one will get a level 1 or 2 classification.

Examining the evidence in the National Digital Mental Health Strategy

Despite the investment in digital mental health tool research, this document resorted to quoting one paper to support its claim of efficacy. The paper is by Gavin Andrews and his team, and is a meta-analysis from 2010 looking at the evidence from 1998-2009. I would have to say the world has moved on.

Related

To be fair, the framework also references the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s (2020) National Safety and Quality Digital Mental Health Standards. This document also references one paper, a more modern one, but one with significant flaws. They use this paper to back their statement that: “There is growing evidence regarding the important role digital mental health services can play in the delivery of services to consumers, carers and families”.

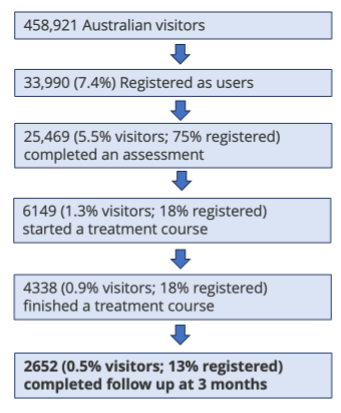

The paper, from 2016, examined the “Mindspot” online clinic. Let’s look at their evidence, or more specifically the cohort. Here’s the attrition of their convenience sample.

So, of the people who ended up on the website (who I suspect are not representative of the broader population) 0.5% finished the study. It doesn’t matter what clever statistics are done on this tiny sample of a tiny sample. It can’t prove anything, except that 99.8% of people who visited the site left before completion.

In any other setting, this would be considered a problem. However, the authors assert in their conclusion that “this model of service provision has considerable value as a complement to existing services, and is proving particularly important for improving access for people not using existing services”.

This is the best paper (presumably) the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care could find.

The impact of digital mental health strategies on mental health policy

The impact of this belief in digital mental health is significant. There has been substantial investment in digital health tools, including mandating the use of the Initial Assessment and Referral Tool to enable stepped care at the PHN level with digital health engagement.

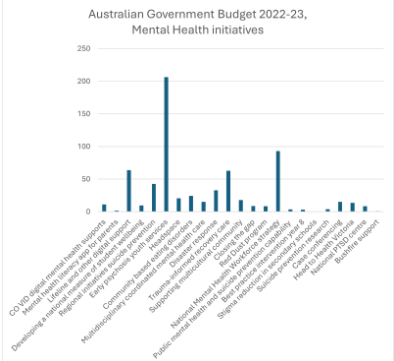

Here is the ongoing investment in digital mental health initiatives, excluding research and other grants:

- 2021-2022: $111.2 million to create a “world-class digital mental health service system”;

- 2022-2023: $77 million on digital mental health services;

- 2023-2024: $500.6 million on helplines and digital services.

The scoping review in 2022 identified 29 digital mental health services funded by the Australian government. Here is the breakdown of budget announcements in the 2022-2023 budget. The budget for digital mental health would cover 308 fulltime GPs doing 40-minute consultations. That’s 887,000 consultations a year.

GPs are a funny lot.

John Snow knew the Broad Street pump in London was causing cholera, even though the reigning officials at the time did not. When governments refused to listen, John Snow worked around them, removing the pump handle himself. He was, of course, right.

The second thing to know about John Snow was that his passionate opponent, William Farr, who was also a GP, changed his mind in the face of the evidence and supported John Snow in his quest to ensure Londoners had clean water. GPs do eventually follow the evidence.

However, we are natural sceptics when it comes to innovation. We’ve seen “miracle” drugs come and go, and “miracle” devices like pelvic mesh cause harm. We can spot marketing and vested interests a mile away.

The National Digital Mental Health Strategy is full of vested interests. Increasing uptake of digital mental health improves the bottom line of many digital entrepreneurs and gives the government the illusion of universal access to care, when in reality most patients miss out on therapy.

It is our job as GPs to advocate for our patients. Digital mental health solutions may well work for some, but are also part of a trend towards “technological solutionism”, a common trend to “solving” complex problems by offering an app.

Evidence-based medicine requires the whole triad of the best evidence, clinical opinion and patient preference. I’m going to be the small boy at the parade here and say digital mental health services are not the “solutions” they claim to be. They lack data, GPs find them useful in a small proportion of their patients, and most patients don’t want them.

This does not make me a Luddite. It makes me an honest clinician fulfilling my ethical obligation to make clinical decisions on evaluating the efficacy of treatment for my practice population.

In my view, the Emperor desperately needs a different tailor.