When diagnosing paediatric headaches, the interplay between lifestyle, psychosocial factors and impact on quality of life must be considered

Headache is a frequent complaint in children. The overall global prevalence of headache in the paediatric population approaches 60%, (1) varying from around 40-50% in school-age children and up to 80% in adolescents according to some studies. (2-4) The high lifetime prevalence is associated with significant burden. (5, 6)

There are many causes of headache and making an accurate diagnosis is key to management. While it is of prime importance not to miss rare but serious underlying pathology, correct diagnosis and appropriate management of the more common primary headache conditions is enormously important in reducing health burdens, such as school absenteeism.

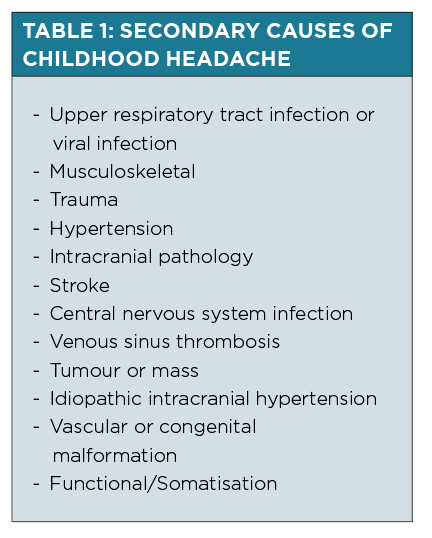

Headaches can be broadly categorised as primary, which is unrelated to another medical condition, or secondary, that is, resulting from another medical condition such as those listed in Table 1.

PRIMARY HEADACHES

Migraine headaches, tension-type headaches and cluster headaches are some of the more common primary headache conditions.

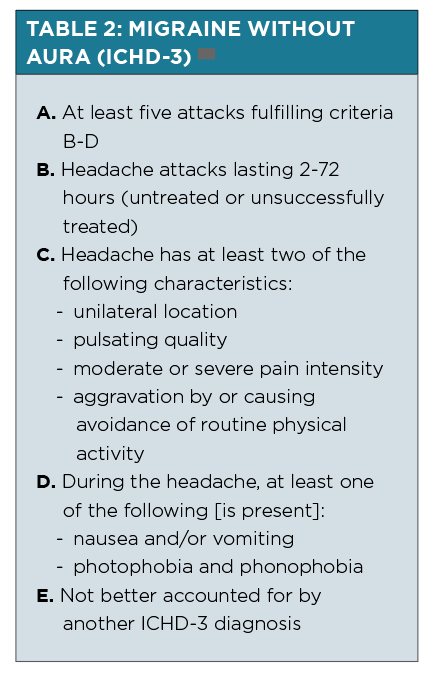

The International Headache Society details the diagnostic criteria in The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3). (7)

Of the primary headache conditions, migraines occur most commonly, with an estimated 8% of the global paediatric population being prone to these over a three -month period or more. (1)

There are several subtypes of migraines with key characteristics for all being recurrent pulsating or throbbing headaches, with nausea or vomiting and/or sound or light sensitivity (See Table 2).

Compared with adults, children tend to have shorter duration migraines (two hours compared to four hours minimum) that can be bilaterally (rather than unilaterally) located.

Younger children often describe migraines in the bifrontal region, with bitemporal regions being more commonly reported in early adolescence.

Although it is common for adults to experience nausea with migraine, children may not describe nausea and present only with vomiting.

Migraine auras, where present, are most commonly visual or sensory symptoms being experienced with gradual onset over five or more minutes preceding a migraine.

Visual auras can be bilateral or unilateral, with or without a relative scotoma.

Children may describe this as “blobs” that come and go.

Sensory aura is usually experienced as tingling or numbness in the fingers or face. Thes eneurological symptoms are fully reversible, so referral to the emergency department should be considered if neurological deficits do not resolve after an hour.

Not uncommonly, migraine headaches may evolve into tension-type headaches and vice versa. (9)

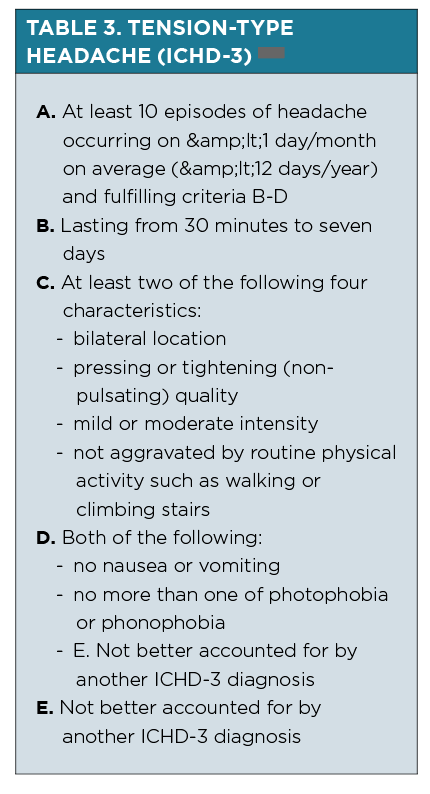

Tension-type headaches may be episodic (See Table 3) or chronic, with a wide spectrum of duration. They are differentiated from migraine headaches by the lack of associated features such as vomiting, photophobia and aura.

Tension-type headaches most commonly occur late in the day and are associated with lifestyle factors such as stress and busy schedules.

Check the home situation, sleep patterns as well as headache occurrence patterns, particularly in relation to school, weekends and holidays.

In children and young people presenting with chronic headaches, defined as more than 15 headache days a month for more than three months, it can be helpful to specifically enquire about use of analgesia, including triptans, NSAIDs and opioids.

Medication-overuse headache is especially observed in adolescents with chronic headaches and is a risk factor for persistence of chronic migraines. It often occurs in a patient with a pre-existing primary headache.

Analgesia should not be used more than two to three times a week in these patients.

Medication-overuse headache usually resolves following cessation of the overused medication. (7, 11)

SECONDARY HEADACHES

Primary headaches can only be diagnosed if they are not attributable to another cause or disorder (See Table 1).

Secondary causes of headaches are frequently benign, the most common being related to an intercurrent infection. (3)

Red flags and clinical evaluation

Serious secondary causes not to be missed include hypertension and intracranial pathology such as central nervous system (CNS) tumours. A comprehensive clinical evaluation should include weight, resting blood pressure, head circumference in small children, temperature and a full neurological examination, including visual acuity, extra-ocular movements, fundoscopy, reflexes and coordination.

Examination of the skin for neurocutaneous features can also provide important clues.

Red flags that should prompt further investigations and consideration of specialist referral include: (12)

– Focal neurological signs, particularly visual or gait abnormalities

– Fever and neck stiffness or other features suggestive of an underlying CNS infection

– Nocturnal or early morning headache and vomiting, or Valsalva induced headache (suggesting raised intracranial pressure)

– New onset seizures

– Age under three to five years old

– Increasing head circumference

– Progressive headache or acute change in headache characteristics

– Cognitive or behavioural changes

If you are concerned about a child acutely unwell needing urgent investigations, they should be referred into the Emergency Department. Consider if an ambulance is warranted for transfer, especially if there is neurological or haemodynamic instability.

Investigations – when is imaging indicated?

Children do not require routine neuroimaging to exclude an intracranial secondary cause of headache if their clinical examination is normal. The yield is less than 1% in this situation. (13) Conversely, incidental findings causing unnecessary worry are identified in up to 19% where neuroimaging is obtained in children with headaches and normal examination findings.

Isolated headache is not usually the only symptom of a serious underlying intracranial cause. If neuroimaging is deemed unnecessary at first, it remains important that children and families have planned review and are re-evaluated should red flag symptoms or new signs develop.

Where focal neurological signs, visual or gait abnormalities are present, neuroimaging should be undertaken as these features are strongly suggestive of a CNS cause. This is recommended in the current and recently reaffirmed American Academy of Neurology evidence-based guideline for

evaluation of recurrent paediatric headaches. (13)

MANAGEMENT

Secondary causes of headache, where identified, require appropriate specific management and are beyond the scope of this article. Where clinical evaluation is reassuring with an absence of red flags and a normal physical examination, consider an underlying primary headache condition to tailor your management approach.

In any primary headache condition, it can be helpful to assess frequency and impact of the headaches for shared treatment goals. Recognising triggers and optimising lifestyle factors is important.

Education of the patient and family is paramount to successful management.

Lifestyle factors

Check daily routines with specific emphasis on ensuring adequate hydration (older children should drink at least 1.5 to 2L of water a day), regular meals, good sleep hygiene and adequate sleep. Limit analgesia use to two to three times a week to prevent medication overuse.

Check attendance at school and other regular activities. Proactively prepare for busy times of the year such as school start months when headache onset rates are higher.

With regards to food, there is little evidence for diet restriction. Chewing gum can be associated with temporomandibular joint pain and headaches, and caffeine intake can contribute to dehydration.

Addressing these lifestyle factors is frequently enough to significantly reduce and prevent primary headaches.

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT OF MIGRAINES

Acute treatment

Abortive treatment of migraines in children is fairly similar to that in adults. A typical plan includes resting in a quiet and dark area to promote sleep which can “switch off” a migraine from progressing.

There is evidence for early use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen. Triptans can be considered in adolescent patients especially where the migraine is not relieved by NSAIDs.(14) Medications for acute migraine are most effective when administered during the migraine prodrome. Where no prodrome is experienced, abortive treatment should be given at the first recognition of migraine.

Triptans are available in a few forms, with intranasal delivery routes (sumatriptan) being more quickly absorbed than if given orally. This can be more efficacious if there is prominent nausea and vomiting. In addition, as there can be individual variability in response, consideration should be given to trialling an alternative triptan, such as rizatriptan oral wafer, if the first triptan tried is not effective.

It should be noted that patients should be counselled to avoid overuse of triptans, and triptans are generally not used for complicated migraines.

For those where outpatient abortive treatment is not successful with NSAIDs or triptans, referral to the Emergency Department can be considered. In hospital, intravenous fluids and medication such as chlorpromazine or prochlorperazine can be effective. Further alternatives such as steroids, ergotamine or valproate can also be considered in consultation with local paediatric neurology.

Prophylaxis

A preventative medication can be trialled in addition to lifestyle measures if there is a clear pattern of one or more migraine attacks per fortnight, particularly if associated with significant impact such as school absenteeism.

In general, it can take at least two to three months for an adequate trial of a prophylactic medication due to therapeutic latency. A common pitfall for failing a preventative medication is inadequate duration of treatment. In addition, 50% or more reduction in headaches, rather than complete prevention, is considered successful treatment.

There are many pharmacological agents available for use and it is important to acknowledge many, while safe, are off-label indication for migraine prevention.

In addition, paediatric patients have a higher placebo response rate of 55%, compared to 35% in adults.

A recent double-blinded RCT comparing amitriptyline, topiramate and placebo for migraine prevention in paediatric patients aged eight to 17 years old terminated early following planned interim analysis.(15) There was no significant change in number of headache days with either intervention compared with placebo or with each other.

Conversely, a significant number of adverse events were reported in those taking either active agent compared with placebo, including fatigue with amitriptyline (30%), decreased weight and paraesthesia with topiramate (8% and 31%).

There is low level evidence in another study that propranolol may be more effective than placebo. (16,17)

Ultimately, most trials do not demonstrate with high confidence effectiveness of any medication beyond that of placebo.

Clinicians should engage in transparent and informed shared decision-making with families before trialling medications for migraine prevention in children.

Additional practice tips for adolescents

Primary headaches in adolescents are often closely linked with social and psychological stressors and this should be addressed early. A holistic approach should focus on daily routines and supported return to school where school absenteeism has been significant.

Involvement of a general paediatrician or adolescent physician can be invaluable in this instance. Even in the absence of mental health concerns, consider involvement of a psychologist.

A recent small study demonstrated cognitive behavioural therapy in conjunction with amitriptyline is more efficacious than headache education and amitriptyline. (18) This practice is recommended in therecently published American guidelines in paediatric headache management. (17)

CONCLUSION

Headache is common in children and adolescents and a frequent presenting complaint to general practice.

Thorough history taking and clinical examination is paramount to guiding appropriate investigations, correctly determining the aetiology and diagnosis, and considering the safest and most effective treatment for the specific headache.

It is important to consider the complex interplay between lifestyle, psychosocial factors, headache and impact on quality of life.

Referral to a paediatric specialist should be considered if there is significant health burden, treatment failure, or if there is uncertainty regarding headache diagnosis.

Dr Natasha J. Saunders is an Australian paediatric senior registrar currently living and completing her postgraduate training in London, UK. She is interested in paediatric neurology and good coffee.

Dr Eunice K. Chan is a consultant child neurologist and paediatrician in Melbourne, Victoria. She completed her specialist training in Australia followed by an overseas fellowship in complex movement disorders in London. She prefers the coffee in Melbourne to that available in London.

References:

- Abu-Arafeh I, Razak S, Sivaraman B, Graham C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(12):1088-97.

- Sillanpaa MA-AI. Epidemiology of recurrent headache in children. In: Abu-Arafeh I, editor.Childhood Headache. London: MacKeith Press; 2002. p. 19-34.

- Conicella E, Raucci U, Vanacore N, Vigevano F, Reale A, Pirozzi N, et al. The child with headache in a pediatric emergency department. Headache. 2008;48(7):1005-11.

- Sixsmith E, Starr M. Managing childhood migraine. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(6):356-9.

- Hämäläinen ML, Hoppu K, Santavuori P. Pain and disability in migraine or other recurrent headaches as reported by children. Eur Journal of Neurology. 1996;3(6):528-32.

- Souza-e-Silva HR, Rocha-Filho PA. Headaches and academic performance in university students: a cross-sectional study. Headache. 2011;51(10):1493-502.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

- International Headache Society (HIS). Migraine without Aura. International Classification of Headache Disorders – 3 rd Edition. 2018 Available from: https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/–migraine-without-aura/ [Accessed 17 th September 2019.]

- Kienbacher C, Wöber C, Zesch HE, Hafferl-Gattermayer A, Posch M, Karwautz A, et al. Clinical features, classification and prognosis of migraine and tension-type headache in children and adolescents: a long-term follow-up study. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(7):820-30.

- International Headache Society (HIS). Infrequent Episodic Tension Type Headache. International Classification of Headache Disorders – 3 rd Edition. 2018 Available from:https://ichd-3.org/2-tension-type-headache/-1-infrequent-episodic-tension-type-headache/[Accessed 17 th September 2019]

- International Headache Society (HIS). Medication-overuse Headache. International Classification of Headache Disorders – 3 rd Edition. 2018. Available from: https://ichd-3.org/8-headache-attributed-to-a-substance-or-its-withdrawal/-2-medication-overuse-headache-moh/ [Accessed 17 th September 2019]

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Clinical Guideline. Headache. Available from:https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Headache/ [Accessed 17 th September 2019.]

- Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Dahl G, Dorbad D, Hirtz D, Prensky A, et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2002;59(4):490-8.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Potrebic S, Billinghurst L, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology.2019;93(11):487-99.

- Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, Ecklund DJ, Klingner EA, Yankey JW, et al. Trial of Amitriptyline, Topiramate, and Placebo for Pediatric Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):115-24.

- Ludvigsson J. Propranolol used in prophylaxis of migraine in children. Acta Neurol Scand.1974;50(1):109-15.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2019;93(11):500-9.

- Kroner JW, Hershey AD, Kashikar-Zuck SM, LeCates SL, Allen JR, Slater SK, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy plus Amitriptyline for Children and Adolescents with Chronic Migraine Reduces Headache Days to ? 4 Per Month. Headache. 2016;56(4):711-6.