People who can’t visualise images with their ‘mind’s eye’ are still doing all the imagination work.

People with aphantasia – the inability to visualise an image inside their head – may have a deceitful mind’s eye rather than a blind one, according to new Australian research.

The study, published this week in Current Biology, looked at signals in the primary visual cortex of people with aphantasia as they attempted to conjure up an image.

Despite the subjects’ apparent lack of success, the researchers found that their visual cortices were still functioning similarly to a person who is able to imagine an object – suggesting their brains were doing the work of creating an image, even if they couldn’t experience it.

That’s a pretty crappy deal, if you ask us.

Around 1.3 million Australians are estimated to be aphantasic, and the population included in the study had their inactive visual imagination assessed via questionnaire and objective binocular rivalry.

The 14 aphantasic participants were asked to imagine or view colourful striped patterns while undergoing a blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) functional MRI scan.

While their BOLD responses were lower than those of the 18 control subjects, the BOLD signal changes of the early visual areas in aphantasic individuals were at a similar level to those in the control group.

Their attempts at imagery could still be successfully decoded, despite the participants’ extremely low scores on imagery vividness and lack of sensory imagery.

“It’s like their brain is doing the math but skipping the final step of showing the result on a screen,” study co-author Professor Joel Pearson said.

“This tells us that mental imagery isn’t just about the brain ‘lighting up’ – it’s about how that activity is formatted into something we can actually experience.”

These findings challenge the assumption that activity in the primary visual cortex directly produces conscious visual imagery.

While the researchers were interested in the broader implications for understanding the brain and the potential implication for mental imagery-associated conditions like schizophrenia, this Back Page correspondent is desperate to know whether it brings us any closer to being able to watch movies in our heads.

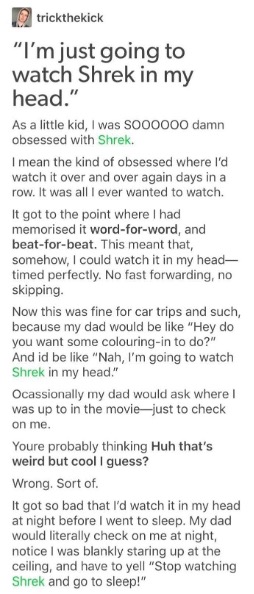

So far, the only person who seems to have cracked that particular code is a Tumblr user going by the handle trickthekick, who claimed to have memorised the movie Shrek to the point where they were able to watch it entirely in their head.

Scoff at my dream you might, but the in-head theatre (copyright pending) is surely one step closer.

Who’ll be laughing then? (It’ll be me, because I’ll be watching Shrek in my head).

Project your story tips on the visual cortex of penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.