The health landscape is filling with dodgy operators who claim to be solving the access problem.

Over the last decade consumers have a seen a rapid expansion in the types of healthcare offerings they’ve got access to online.

Pressed on by the pandemic and limited to access to face-to-face primary care, internet-native entrepreneurs have moved into the digital healthcare space, cashing in on the seismic void left by the failure of legacy healthcare providers to substantially innovate on the way they deliver care.

But as we have seen time and time again in healthcare innovation, when the pioneers of the innovations are from a non-clinical space, their novel ideas present a double-edged sword for the ecosystem as a whole.

On the one hand, they bring a welcome injection of naivety that helps them see past perceived barriers to change and thereby push the limits of healthcare delivery. But on the other, their willingness to depart from healthcare standards in pursuit of sales is likely in conflict with the best interests of the patients they claim to serve.

Companies in the online healthcare category also appear to be more willing to charge high prices for either low-quality consults, or in extreme cases, consults with no genuine intent to optimise health, but rather achieve some secondary aim such as a delivery of a medical certificate or to sell a drug of interest.

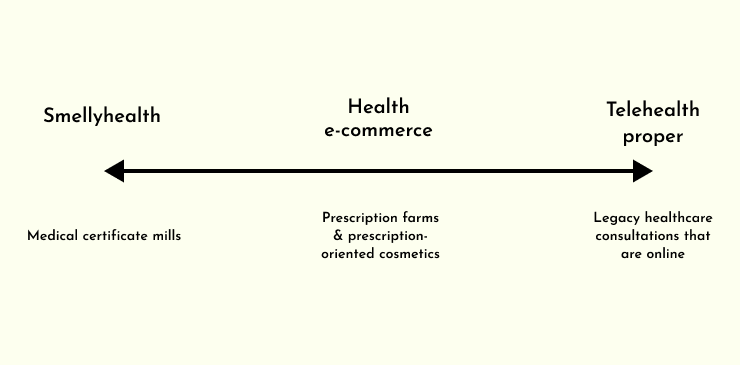

In fact you can broadly categorise companies in the telehealth space based on their characteristics:

At the dodgiest end of the spectrum, a category I’m labelling “Smellyhealth”, you find companies that make no genuine effort to deliver any sort of healthcare, despite often brigading themselves as a solution to Australia’s primary care crisis.

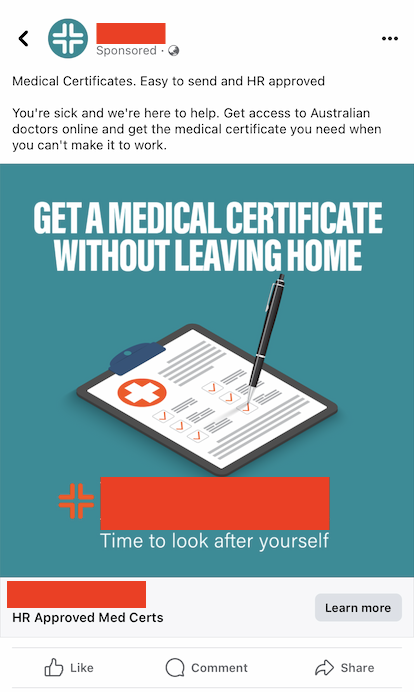

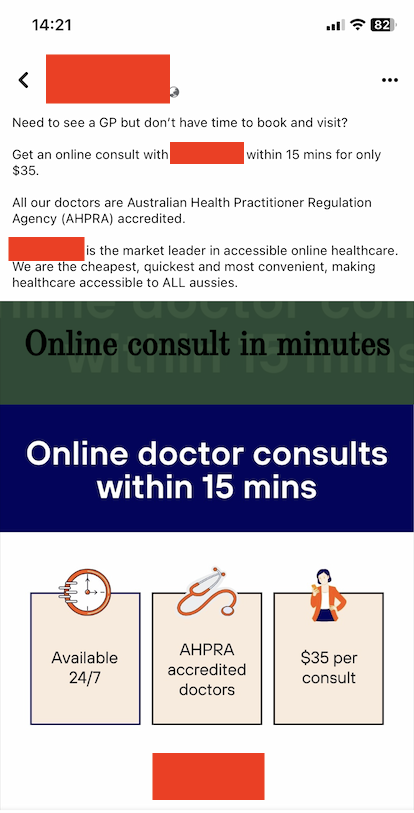

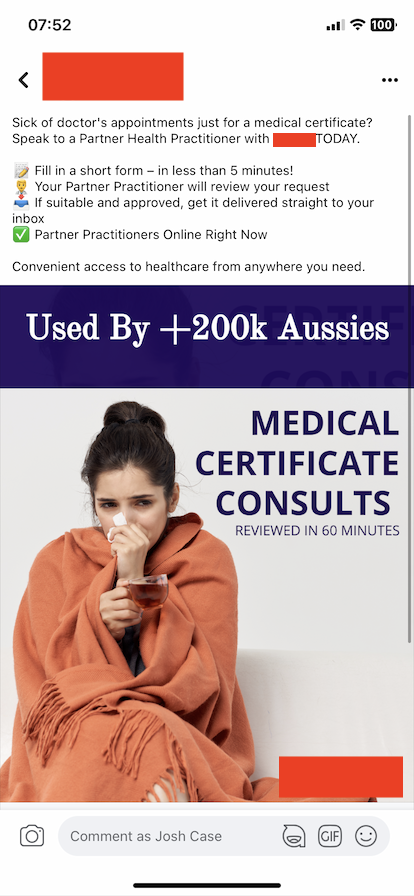

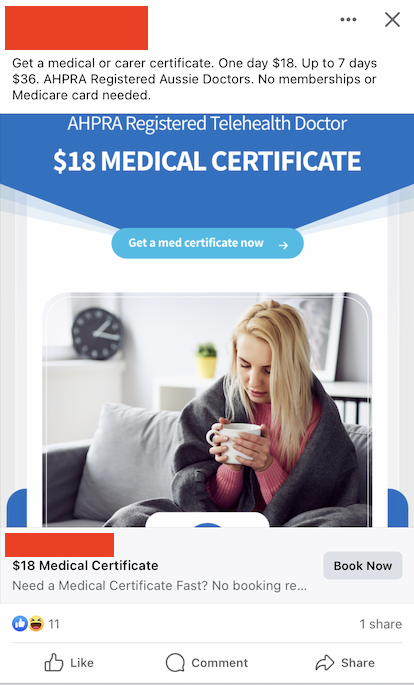

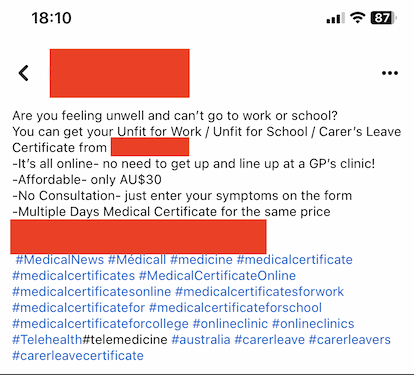

By far the biggest Smellyhealth subcategory is medical certificate mills, which have erupted on the scene over the last five or so years. These companies offer a superficial “consult”, often a few tick and flick boxes, in exchange for an automatically generated medical certificate that says you’re not fit for work for however long.

And there are literally dozens of companies that operate like this, hammering their ads away into newsfeeds nation-wide:

It’s reportedly a big business, too. This one claims to have been used by 200,000 Australians (hard to know if this is accurate or not), but at $20 a pop, we’re looking at millions of dollars of trade just for one of these certificate mills.

For whatever reason, I find the following ad particularly egregious. Surely the duration of the medical certificate should be based on the clinical need, not the patient’s willingness to pay. At least try to pretend that you’re in some way legitimate.

This one even brags that there’s “No consultation”. How can you have messaging like this and then expect that certificate to be worth anything at the end?

Having written dozens or hundreds of medical certificates myself over the last five years of clinical practice in public hospitals, I’ve sort of always been aware that these certificates aren’t particularly useful or meritorious beyond meeting superficial HR requirements.

But to any employer reading this, especially now, certificates like these aren’t worth the paper (or the PDF) they’re written on. Until employers stop gatekeeping their employees’ sick days, I’m sure this will remain a thriving industry and provide a genuine convenience for consumers, albeit without any measurable health outcome.

Further along the spectrum, some distance away from full-on Smellyhealth, but still a reach away from telehealth proper, you’ve got an exploding basket of companies you can collectively think of as the health e-commerce group.

These companies often have their roots in other non-health oriented e-commerce brands, and come into the health space with a similar B2C sales mindset. Their goal is find the most commercially popular pharmaceutics, mark them up, and then sell them ad nauseam using digital marketing techniques.

They may offer some superficially valuable consultation at some point in their workflow, (primarily targeted at identifying contraindications to the use of their pet medications to protect themselves) but are also unlikely to recommend therapies that aren’t aligned with their financial interest.

The Medical Board acknowledged the risks of this type of prescribing behaviour when they cracked down on asynchronous consults that result in prescription last September.

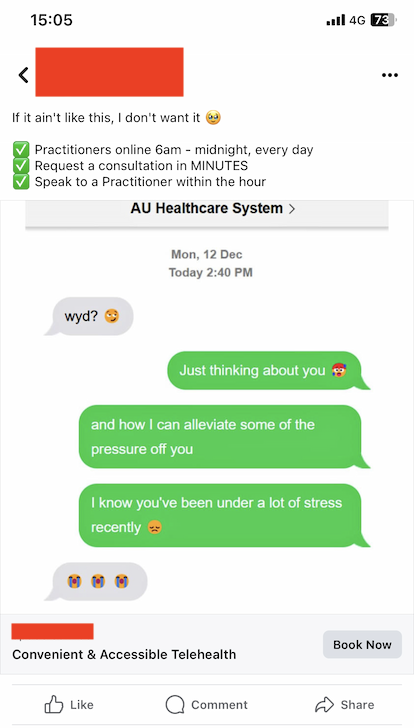

As a result of their e-commerce background, these companies are also willing to resort to murkier advertising approaches than healthcare proper, designed to squeeze every little decimal point of value out of their conversion rates, even at the expense of the customers themselves.

Examples include playing on themes that people who are overweight are unattractive, or men who have erectile dysfunction are inadequate in the eyes of their partners, and so on.

They also have greater risk appetite to flirt with breaches of the AHPRA Guidelines for advertising a regulated health service and the TGA’s guidelines for advertising therapeutics. If you peruse many of the leading health e-commerce websites, you won’t have to look for long to see many statements that could be at odds with these rules.

This mindset likely doesn’t benefit consumers.

In fairness, there are situations where this type of marketing will enable patients to get access to a certain type of therapy that they would otherwise not have sought, but that segment seems to be small relative to the overconsumption of therapeutics that systems like this incentivise.

But what’s the problem?

I’ve heard people say things like “if they’ve got a registered doctor making a legitimate prescription to a consenting patient, what is your issue with this?” And at a high level, I agree.

In this day and age, patients should have a high degree of autonomy in determining what treatments or drugs are right for them.

But the whole reason that prescriptions are necessary in the first place is because there are situations where patients don’t know what they don’t know. And I say that as someone who fully accepts and acknowledges the holes in my own knowledge – but I think it’s fair to say it’s better than that of the average layperson.

And when a patient presents with a particular problem, is a company that is incentivised around rampant prescription and consumption of therapeutics really a credible source of information in this situation?

Essentially, the incentives are set up in a way that couples drug consumption and financial gain, which can’t be a good thing in the long term.

(I’m also painfully aware of the irony of me whinging about their economics, when most excessively patient-centric digital health startups fail because they have nothing close to a business model that makes financial sense. Aligning incentives appropriately in healthcare is extremely difficult).

In the case of medical certificate mills, the issue is not so much the consumption of drugs, but the repeated process of profiteering off the the general credibility of our profession. They’re essentially leasing their medical licences on the street for pennies, ever so slightly eroding the community’s trust in the authority of medical practitioners.

When I write a letter, I want that to mean something. And on the path we’re on at the moment, it won’t be that way for long.

There are other annoying, but perhaps less-pressing objections I have to Smellyhealth practices, too.

For one, healthcare information is siloed enough as it is, and the last thing we need is more cooks in the kitchen who aren’t adequately equipped to communicate. I would really encourage any telehealth provider to provide the functionality to loop a patient’s GP in on any changes to their medications to ensure continuity and safety.

Another pet peeve (an ick, if you will) is when Smellyhealth companies brand themselves as part of a genuine solution to problems in Australia’s healthcare ecosystem.

And BOY do they love to do this!

Fixing our aged care crisis, one Ozempic script and medical certificate at a time.

To be crystal clear, I’m a huge supporter of digital health and I do credit these companies for pushing our space forward in a way legacy healthcare would never have been able to alone. And we certainly need them in the fight against the health challenges that are in Australia’s future.

But I think it can be done right and it can be done wrong, and working out which companies are doing which is getting harder and harder by the day for patients.

Josh Case is a medical doctor, a software developer and the chief technical officer at Go Locum.