When it comes to public health campaigning, sugar is fast becoming the new tobacco

Shocking sights at Melbourne tram stops over summer are just one sign that the fight against “Big Sugar” is taking a serious turn.

The AMA came out swinging in the first week of the new year with a new position paper calling for a ban on the advertising of junk food and drinks aimed at children and restating its support for a sugar tax. AMA President Dr Michael Gannon emphasised that his organisation would maintain pressure on government, saying that Australia’s sugar habit was as much doctors’ business as the scourge of smoking.

“We see this as comparable to the war on tobacco,” Dr Gannon said. “We think that, bit by bit, we need to change behaviours. We need to drag the government to action with a variety of measures.”

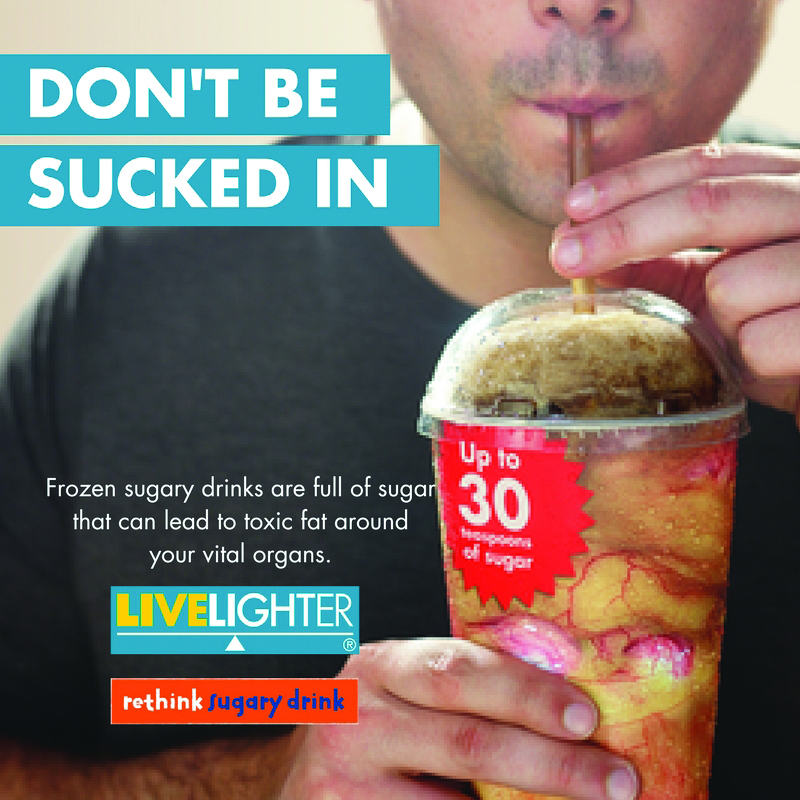

The AMA’s call coincided with the roll-out of the truly sickening advertisements in Melbourne, showing a man drinking a cup of venous toxic fat to highlight the sugar content of cheap frozen drinks.

The campaign, which originated in Western Australia, also uses blunt statements about sweetened drink products, who sells them, and how much sugar they contain.

A $3 cola “mega slurpee” from a 7-11 convenience store, it reported, contained more than 20 teaspoons of sugar that would take an hour and 17 minutes of walking to burn off. A Hungry Jacks jumbo frozen Coke had over 18 teaspoons.

“We know the junk food and drink industry spends a huge amount of money on advertising. We are bombarded with promotions and advertising that make it harder to make a healthy choice. We wanted to counteract that,” LiveLighter WA campaign director Maria Szybiak said.

The art of the message extended to placing the ads where children and other consumers are likely to be thinking about purchasing a thirst-quenching treat.

“So when you’re thinking of going to the store, you are hit in the face with how much sugar is in the sugary drink.”

LiveLighter WA, managed by the Heart Foundation and the Cancer Council with support from the state government, has been going since 2012 and is funded to the tune of $4 million a year, allowing it to run longer campaigns and hire billboards as well as bus shelters.

“The broader campaign is really well received by the target audience – people who are overweight or obese relate more to the campaign than those in a healthy weight range – which is part of what we are trying to do,” Ms Szybiak said.

In Victoria, budget constraints confined the poster blitz to just two weeks in January. But the Don’t Be Sucked In campaign continues, overseen by a partnership between the state’s LiveLighter branch and an alliance of 18 public-health bodies, including dentists and Aboriginal health groups.

Like the anti-tobacco movement, the anti-sugar campaign aims to take territory away from sugar merchants.

Jane Martin, executive director of the Obesity Policy Coalition, said the objectives were to reduce the marketing and availability of sugary drinks, particularly to children as well as raising awareness of health risks. “We’ve got quite a bit of experience from tobacco control around the development of advertising to change behaviour,” she said.

“We know that personalising the messaging, that this is happening in your body – which was the same tactic as the message that every cigarette is doing you damage – is very powerful,” she said.

“That’s where these ads are certainly a stand-out in the word of public education, and diet in particular.”

Increasingly, doctors were acknowledging that problems of obesity and overweight could not be addressed in the consulting room, she said.

Professor of Public Health at Griffith University Lennert Veerman said a sugar tax could lead manufacturers to lower the sugar content of their product to avoid a penalty.

“Just informing people is not going to change anything. We have to change the environment,” he said.

“With tobacco, it was necessary to shock people to make them aware of the risks of lung cancer, then we moved on to restricting sale of cigarettes to minors and smoking in the workplace.”

Dr Gannon said Australia should follow other countries in adopting a sugar tax to act as a deterrent and to fund public-health education.

“Over time, this would reduce consumption. So, over time, it would reduce the burden on householders.”