There is strong evidence for surgical management of four common lumbar disorders... but which ones?

Back pain affects 13% of the Australian community on any given day, with 70% to 90% of Australians suffering from back pain at least once during their lifetime.1

Chronic back pain is defined as back pain lasting for more than three months.

According to recent US data, low back pain is the leading cause of musculoskeletal pain, affecting 28.6% of the population. By comparison, neck pain affects 15.2%.2

In recent years, two factors have caused uncertainty for GPs managing low back pain:

• Alarmist media reports questioning the validity of elective surgery for degenerative conditions of the spine;

• While able to rule out pathological causes quickly, radiologists’ reports featuring words such as “disc desiccation, degeneration, annular tears, compression and bulges” can be hard to interpret and can become a source of catastrophisation for people with pain hoping to pinpoint a cause.

This article discusses four lumbar disorders that present commonly in general practice and may benefit from a surgical opinion. This will not necessarily lead to surgical management; the diagnosis in itself is not an indication for surgery. However, current evidence reflects good outcomes following spinal surgery for these cases.

The four lumbar disorders that can benefit from surgical consultation if symptoms are non-responsive to conservative management are:

1. Herniated nucleus pulposus

2. Spinal canal stenosis

3. Adult lytic/isthmic spondylolisthesis

4. Degenerative spondylolisthesis

It is imperative to rule out neoplastic, inflammatory and infective causes when patients present with back pain. The following are red flags to watch for:

• History of significant trauma (e.g. fall, MVA, heavy lifting)

• Bowel or bladder incontinence or urinary retention

• Associated fever, night sweats +/- unexplained weight loss

• Age <16 or >50 with new onset pain

• Cauda equina syndrome

• History of cancer

• Long-term steroid use

When these red flags are detected, referral to ED or a spinal specialist is indicated.3

Herniated nucleus pulposus

Disc herniation, or herniated nucleus pulposus, accounts for 5% of all low-back disorders. Sciatica – a radiculopathy resulting from compression or irritation of one or more spinal nerve roots, with neuropathic pain radiating down the affected side – is a common presentation.

Clinical examination is likely to reveal a positive straight leg raise and expose deficits in a neurological examination. These deficits depend on the level of the lesion: for example, herniation at L4/L5 disc is likely to cause L5 nerve root irritation, which in turn can produce numbness and tingling along the L5 dermatome, as well as weakness of the extensor hallucis longus.4

Ideally, patients should be managed conservatively with analgesia, light exercise and heat packs for six to eight weeks, and referred for imaging and to a surgeon if there is no improvement. However, severe presentations, the presence of red flags (especially of cauda equina syndrome) and rapid progression of symptoms and signs may require urgent referral.

Steroid injections can often be used to reduce pain, however, their main role is to provide early pain relief in the interim to surgery, in addition to the diagnostic role in predicting the level of the lesion5.

Patients who fail to improve after six to eight weeks of conservative treatment for a herniated disc, and where clinical presentation correlates with radiological findings, are likely to find fast symptomatic relief from microdiscectomy.

Microdiscectomy is the latest form of surgery where the surgeon uses a microscope to remove herniated parts of the disc that may be irritating nerves or occluding the spinal canal. The timing of surgery is important due to evidence that delaying microdiscectomy beyond six to nine months may worsen clinical outcomes.6

Patients who demonstrate concurrence between neurological symptoms and radiological signs are the most likely to benefit from microdiscectomy. For example, numbness and tingling in L5 dermatome, which correlates with a lateral herniation of the L4/L5 disc, is likely to improve with microdiscectomy, with current evidence supporting a rapid relief of sciatica and the debilitating effects of such pain, especially at six months.7

There is, however, no evidence at present that surgery alters the natural history or long-term prognosis of herniated nucleus pulposus. A Cochrane Review analysed 42 papers and determined that at 24 months post-surgery there was no significant difference between surgical and conservative groups.

Spinal canal stenosis

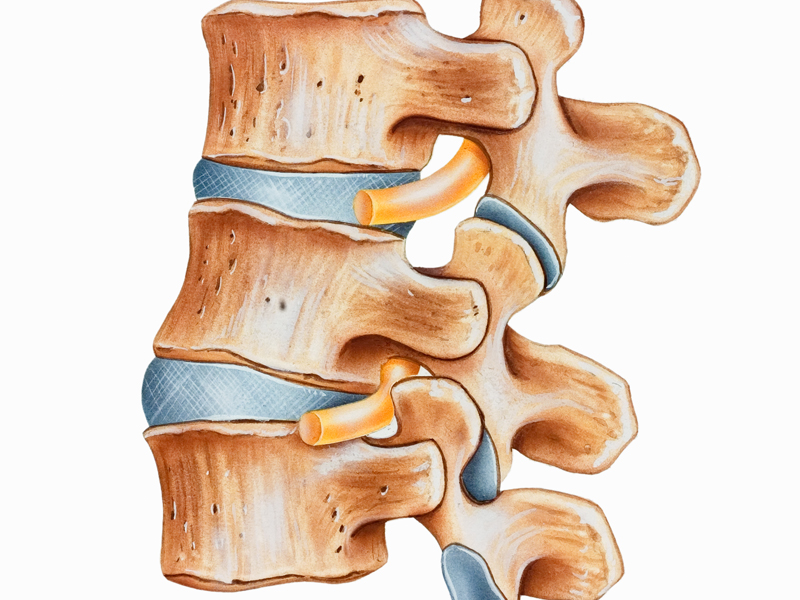

Spinal canal stenosis is the most common reason for spinal surgery in patients over the age of 65 years.8 It may result from several aetiologies, which include thickening of the facet capsule, disc herniation and osteophytes, all of these leading to narrowing of the spinal canal. The hallmark of spinal canal stenosis is spinal claudication: pain and cramping in the leg during and after walking, which is relieved by sitting down.

As with most back disorders, spinal canal stenosis can also be an incidental finding on imaging and may not be associated with low back pain.9

Management of spinal stenosis is determined by the main cause of the narrowing. Currently, laminectomy is the gold standard for symptomatic stenosis that is not responding to conservative management. Laminectomy involves removing the vertebral arch to essentially decompress the spinal nerves.

Newer operations include intervertebral process devices, which work by enlarging the neural foramen and ecompressing the spinal cord. These techniques show better results than conservative treatment when using the Zurich Claudication Questionnaire, however, further research is recommended before they are adopted for generalised use.10

Other new procedures include unilateral, bilateral or split-spinal process laminotomy. Despite these operations minimising damage to muscles and ligaments, there is not sufficient evidence at present to support routine use of these methods.

Lytic/isthmic spondylolisthesis

Lytic spondylolisthesis occurs as a result of an acquired pars interarticularis defect. The pars is located between the inferior and superior articular processes of the facet joint. The defect can result from micro-traumas from sports that involve repetitive hyperextension, such as weightlifting and gymnastics. The vast majority occur at L5/S1. Patients commonly present with back and possibly leg pain, occasionally with claudication. L5 radiculopathy (weakness of ankle dorsiflexion and extensor hallucis longus weakness) can also be present.11

As for most back conditions, non-operative management is first-line. This involves analgesia, braces and lifestyle modifications, including restricting work duties such as lifting, bending and twisting movements that can exacerbate pain. When conservative management has failed, three surgical options (or combinations thereof) are available:

• Fusion of two adjacent vertebral segments

• Decompression

• Repair of the pars defect with screws

Fusion and pars repair produce similar clinical outcomes (good or excellent outcome in 80% to 88% of cases), however, repair has been associated with better rates of return to work (80%) than fusion (60%).12 Decompression can be used in conjunction with fusion with similar outcomes.13

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is the result of the ageing process, which causes one or more vertebrae to slip forward. This occurs most commonly at L4-L5 level. Patients usually present with low back pain, which may be associated with a radiating leg pain. Again, non-operative treatments can be used as first-line management, however surgical treatment with fusion can be used as an alternative when symptoms persist or become unbearable.

In patients with spinal stenosis resulting from degenerative spondylolisthesis, decompression +/- fusion provides substantially better pain relief and function, measured up to four years, when compared to usual non-operative management including physio, education and counselling.

However, in a subset of patients with leg symptoms or claudication, decompression alone (instead of in combination with fusion) may serve as an effective surgical tool. As with disc herniation, surgery serves to provide immediate relief from pain and to improve function.14 It does not change the course of the underlying disease.

Degenerative disc disease

One of the commonest causes of non-specific low back pain is degenerative disc disease.15 This can result in radiculopathy or myelopathy due to a loss of disc space height, bulging discs or osteophytes.

In most cases this condition is asymptomatic and merely an incidental finding on imaging: in one study, 97% of patients demonstrated degenerative disc disease, yet 53% had reported no associated back symptoms.15 Conversely, in some patients disc degeneration can cause chronic low back pain that varies in severity and presentation with no clear radiological correlation for the cause of the symptoms.

The surgical management of degenerative disc disease is outside the scope of this article due to a significant variability in outcomes. This is best discussed in a specialised surgical unit that can provide comprehensive spinal care with a multidisciplinary approach.

Non-operative back pain

The management of back pain for patients whose symptoms last beyond three months and have no significant radiological findings or concurrent pathology presents a challenge. At this point, the patient becomes a “chronic back pain sufferer”. Addressing all components of the bio-psychosocial aspect of back pain beyond analgesia is a crucial part of the management.

In the short-term, management of pain is essential with NSAIDs. Opioids have been shown to have short-term efficacy when compared to placebo to reduce pain and improve function, but have not been demonstrated to be superior to NSAIDs in a few limited studies. It is therefore recommended to assess the benefit-risk profile, time frame of likely use, side-effects from opioids and response from other analgesia before prescribing such drugs.16 Injection of anti-inflammatory and local anaesthetic agents into areas around the nerve, or block of the facet joints, may also be of help for people with chronic back pain.17

Patients are encouraged to stay active and focus on building up their core muscles. This can be achieved by a number of methods including Pilates, physio and yoga. Physio has the most evidence for significant improvements of back and leg pain.18

Pilates has also been demonstrated to improve pain and disability, although these studies are of lesser quality.19

Multidisciplinary bio-psychosocial rehabilitation programs have been shown to reduce pain and disability. Such programs involve a combination of physical, psychological and educational aspects provided by allied health members with training in spinal injuries, including physios, GPs, specialists, nurses and occupational therapists.20

It is crucial that low back pain is not treated as a stand-alone physical component, and that each patient is assessed and managed at an individual level, taking into account pain, functioning and radiological signs.

Megan Grigg, B Med (Scholar), is a final year medical student, intending to follow a surgical career.

Dr Ashish Diwan, PhD FRACS FAOrthA, is the Chief of Spine Service at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, St George Hospital, and Clinical Academic Senior Lecturer at the St George & Sutherland Clinical School, UNSW.

References:

1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Back problems 2016 [Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/back-problems/what-are-back-problems/.

2. Andersson G, Watkins-Castillo S. Spine: Low Back and Neck Pain. United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States. 2012.

3. Bratton RL. Assessment and management of acute low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(8):2299-308.

4. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. Bmj. 2007;334(7607):1313-7.

5. Sethee J, Rathmell JP. Epidural steroid injections are useful for the treatment of low back pain and radicular symptoms: pro. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(1):31-4.

6. Sabnis AB, Diwan AD. The timing of surgery in lumbar disc prolapse: A systematic review. Indian J Orthop. 2014;48(2):127-35.

7. Gibson JN, Waddell G. Surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):CD001350.

8. Ciol M, Deyo R, Howell E, Krief S. An assessment of surgery for spinal stenosis time trends, geographic variations, complications and reoperations. J Amer Geront Soc. 1996;44:285-90.

9. Overdevest GM, Jacobs W, Vleggeert-Lankamp C, Thome C, Gunzburg R, Peul W. Effectiveness of posterior decompression techniques compared with conventional laminectomy for lumbar stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(3):CD010036.

10. Jacobs WC, Rubinstein SM, Willems PC, Moojen WA, Pellise F, Oner CF, et al. The evidence on surgical interventions for low back disorders, an overview of systematic reviews. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(9):1936-49.

11. Moore D. Adult Isthmic Spondylolisthesis 2016 [Available from: http://www.orthobullets.com/spine/2038/adult-isthmic-spondylolisthesis.

12. Champain S, David T, Mazel C, Mitulescu A, Skalli W. Long-term outcomes evaluation after pars defect repair in adult low-grade isthmic spondylolithesis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2007;17(4):337-47.

13.

Nooraie H, Ensafdaran A, Arasteh MM. Surgical management of low-grade lytic spondylolisthesis with C-D instrumentation in adult patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119(5-6):337-9.

14. Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Zhao W, Blood EA, Tosteson AN, et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2009;91(6):1295-304.

15. Miller JA, Schmatz C, Schultz AB. Lumbar disc degeneration: correlation with age, sex, and spine level in 600 autopsy specimens. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13(2):173-8.

16. Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC. Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD004959.

17. Zhou Y, Abdi S. Diagnosis and minimally invasive treatment of lumbar discogenic pain–a review of the literature. The Clinical journal of pain. 2006;22(5):468-81.

18. Chan A, Ford J, Hahne A, Surkitt L, Richards M, Slater S, et al. 1 year results of a randomised controlled trial comparing subgroup specific physiotherapy against advice for people with low back disorders. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2016(1).

19. Yamato TP, Maher CG, Saragiotto BT, Hancock MJ, Ostelo RW, Cabral CM, et al. Pilates for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(7):CD010265.

20. Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJ, Ostelo RW, Guzman J, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(9):CD000963.