The government’s response to the ‘deadly march’ of the overdose crisis has been described as ‘wholly inadequate’.

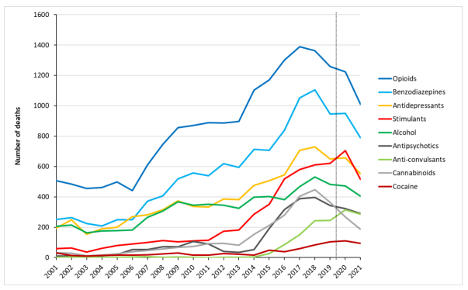

Unintentional deaths involving stimulants have increased five-fold and those with benzodiazepines have doubled in the past two decades, according to a new report by the Penington Institute.

One Australian dies from an overdose every four hours – totalling 2231 nationally in 2021 – as drug overdose “continues its deadly march”, according to Penington Institute CEO John Ryan.

While opioids remain the number one drug involved in fatal overdoses in Australia, the proportion of deaths caused by opioids has stagnated at just under half of all drug-related deaths in recent years.

Attention has instead turned to other drugs such as benzodiazepines – commonly used for stress, anxiety and insomnia – and stimulants such as amphetamines as their death toll rises.

Number of drug-induced deaths in Australia, by drug type, 2001-2021 Note: Data to the right of the dotted line (2020 and 2021 data) are preliminary, and likely to rise. Credit: Penington Institute

Speaking to The Medical Republic, Dr Hester Wilson, chair of the RACGP’s Addiction special interest group, said that major concerns around benzodiazepine use included long-term use and interactions with other sedating medicines.

“When they’re used to their best effect, they’re brilliant, they’re lifesaving,” she said.

“The issue [is when] they’ve been used long term. On their own, most people aren’t going to come to much harm. But once you get stuck on them, it’s really hard for people to stop.”

On stimulant use, Dr Wilson raised concerns about the increased risks.

“What we’re seeing with stimulants is that they’re cheap and they’re high potency. We’ve seen this increasingly over the last few years, you’re going to get more harm from them as a result – death by misadventure or death through heart attacks or strokes,” she said.

While less than 1% of fatal overdoses in 2021 were due to benzodiazepines alone, these drugs – prescribed to one in 20 Australians – were involved in 66% of deaths involving multiple drugs.

Stimulants were involved in 35% of poly-substance deaths.

Between 2017 and 2021, over two-thirds of unintentional fatal overdoses involved two or more drugs.

Mr Ryan said the government’s response to the issue was “wholly inadequate compared to the scale of the problem” and called on the political leadership for a National Overdose Prevention Strategy.

“It is not too late to design and deliver an effective and coordinated response to address the overdose crisis we face. Let’s remember that we have both the means and the methods,” he said.

“We know overdose is preventable. This year’s report reminds us that our task now is to act.”

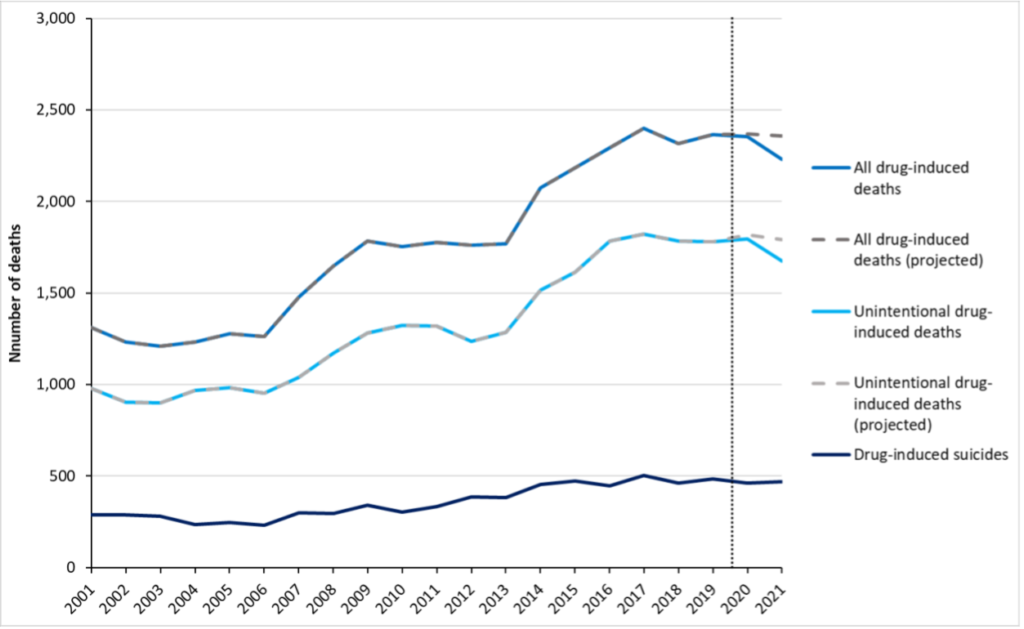

Overdose is a leading cause of death for Australians, surpassing road accidents back in 2014. The gap has only widened since then, predominantly due to increasing unintentional deaths as increases in drug-related suicides have remained minimal.

Number of unintentional drug-induced deaths and drug-induced suicides compared with all (total) drug-induced deaths, 2001-2021. Credit: Penington Institute

In 2021, overdose was the second most common cause of death for men and women aged 30-39 and third leading cause of death for people in their 20s and 40s.

Since 2001, unintentional fatal overdose has increased by 71% – an increase significantly outstripping population growth of 33%. The increase has been seen mostly in over-60s, who now make up 40% of all fatal overdoses.

But increases were disproportionally high in First Nations communities. The incidence of overdose was more than three times higher in Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous Australians in 2021.

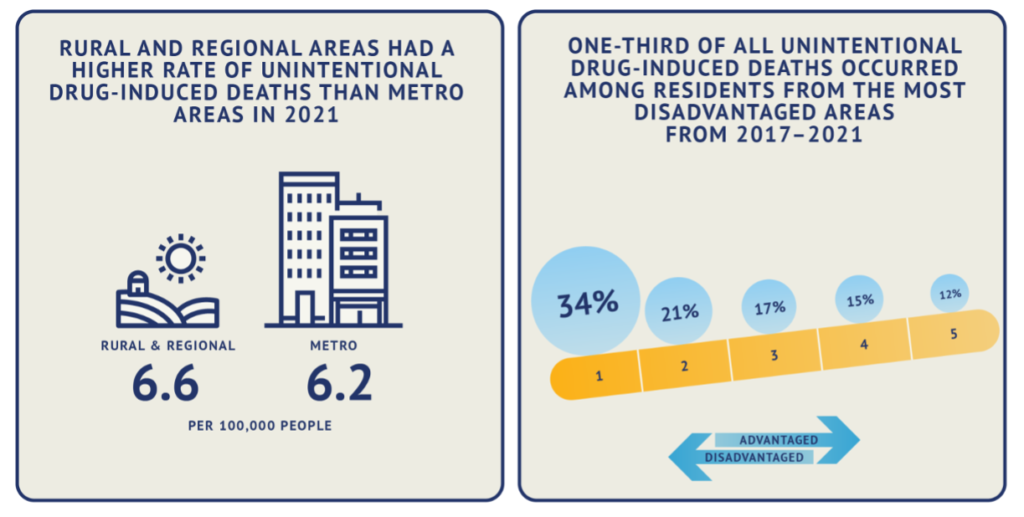

“It’s a worse problem in regional and rural areas but it affects people from all walks of life, including from the richest to the poorest,” said Mr Ryan.

Beyond unintentional overdoses, Australia had the highest number of drugs-induced suicides per 100,000 in 2017-21 compared to Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Asia, the Americas and Oceania and Antarctica (minus Australia).

Drugs and alcohol have also had other non-fatal effects on Australians. These included increasing hospitalisations – over 150,000 in 2020-2021 – and acute and chronic long term health effects of non-fatal overdoses such as low blood pressure, heart rhythm disturbances, abnormal body temperature, liver injury and reduced breathing.

According to Mr Ryan, favouring supply-reduction over harm-reduction strategies in drug policy is a major roadblock to improvements.

“Real-time prescription monitoring might unintentionally prevent people from accessing the opioid pain medications that they so desperately need, yet it has been rolled out absent evaluation,” he said.

“Compare this to harm-reduction measures, which are typically subject to time-consuming evaluations and then receive meagre funding for implementation, especially when it comes to workforce development and support.”

Mr Ryan also flagged defunding of education resources – particularly The Bulletin, a specialty publication for workers taking on Australia’s drug crisis – as a means of robbing workers of support and silencing “a voice of reason in relation to drug use issues”.

However, Mr Ryan highlighted some “encouraging actions” undertaken by the government this year, including increasing access to opioid addiction treatment through removal of exorbitant fees, continuation of overdose prevention services in Melbourne and naloxone becoming a staple of WA police officers’ armory.

“Though these developments can seem piecemeal, they are certainly to be celebrated,” he said.

“It is not too late to design and deliver an effective and coordinated response to address the overdose crisis we face. Let’s remember that we have both the means and the methods.

“What we need now is the political leadership that can take us towards the development of a comprehensive national overdose prevention strategy to reduce and prevent overdose deaths.”

Mr Ryan also said important initiatives had been rolled out to better monitor prescriptions and improve early warnings of contaminated drugs.

According to Dr Wilson, ultimately the answer lay in increasing patient and prescriber education to ensure informed decisions are being made.

“We really do need to rethink the whole way we provide those services. We need to rethink the way our own biases around people that have complex needs play into and really adversely affect [patients’] access to treatment and to continued treatment.

“We need to have ongoing education and support for us as healthcare providers around how we do this better.

“And we can’t do it all on our own as GPs.”

Dr Wilson said medicine sharing was also a danger.

“It really is about educating our communities that there is a reason why medications are on prescription: because they have risk.

“We know that around about 30% of medications are shared.

“[We need to] encourage someone to go and seek assistance and get help and get the right medications for them, rather than medication sharing.”