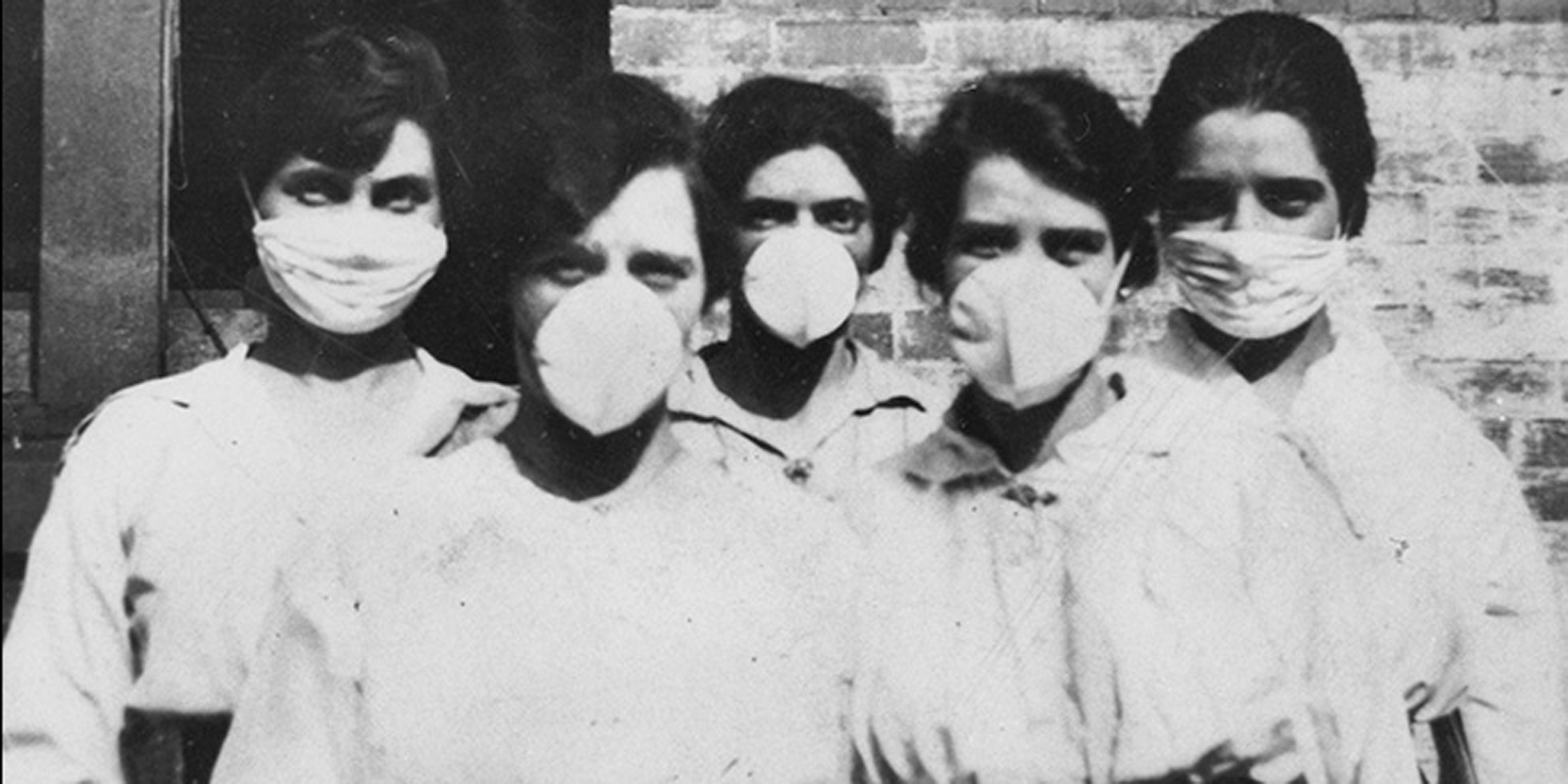

The leaks and gaps in Australia’s pandemic flu plans, and the absence of emergency response drills, have experts very worried

The leaks and gaps in Australia’s pandemic flu plans, and the absence of emergency response drills, have experts very worried.

When the virulent strain of influenza A (H1N1) spread through Melbourne in mid-2009, the cracks in emergency response plans quickly became apparent to the GPs and pathologists on the ground.

The outbreak strained health services, with more than 37,000 infections, nearly 5000 hospitalisations, and around 680 admissions to intensive care.

“Our 2009 experience was of huge gaps and deficiencies,” Melbourne GP Dr Peter Eizenberg, who was at the frontline of the outbreak in northern Melbourne area, said.

Little had been done to address the problems since, Dr Eizenberg told the Influenza Specialist Group annual scientific meeting this month.

Bracing for the 2009 emergency, GPs turned to the RACGP’s Pandemic Influenza Toolkit, and other online resources.

“The writing on the pages seemed very good at the time, and seemed to address the contingencies of emerging characteristics of a pandemic as it evolved,” Dr Eizenberg said.

But there was a large gap between the rhetoric in the written response plans and the reality of what really occurred. “What we missed was the bit between the lines,” he said.

Initially, GPs could not get approval for testing individuals unless they had returned from Mexico, where the pandemic flu virus had emerged, or had contacts with the pandemic flu.

However, the flu virus was spreading and evolving very quickly, and very quickly many individuals who had not travelled to Mexico were infected, and these people were ineligible for testing.

“How could we communicate that? There were no mechanisms. So there we were trying to describe our experience and it took weeks for these case definitions to change,” Dr Eizenberg said.

GPs also did not expect that the approval process for testing and treatment would take half an hour per patient. “It completely paralysed us,” he said.

“And that was all despite having tight networks on the ground and nationally coordinated divisions of general practice,” he said.

Another pressure point during the 2009 emergency was demand for testing, clinical Professor David Smith, a medical virologist at PathWest in Perth said.

“The wheels didn’t fall off, but they got very wobbly,” he said.

Pathology labs saw a huge spike in the number of test requests during 2009. The labs had to handle a substantially higher test load, while simultaneously developing and validating new tests.

“I don’t think we’ve got our act together in terms of … how we deal with surge capacity,” Professor Smith said.

The urgent demand for information from a multitude of stakeholders also stretched the resources of pathology labs. “Everyone wanted to know everything all the time and that was too demanding,” he said.

Pandemics did not unfold as expected, and while plans provided some ideas about what could happen, they are only a framework. “It should not be followed gospel and verse,” Dr Andrea Forde, the ANZ medical director of vaccines at GSK, said.

“You should throw it out the moment it’s not supporting your response,” she said.

Building in contingencies required regular emergency response drills, but Australia had not done any pandemic exercises since 2006, she said. “We need to prepare, we need to practise.”